After breakfast at the InterContinental Lyon, we headed over to Chambery, a former capital of Savoy, for the day. The weather wasn’t great. We ended up visiting the Cathédrale Saint-François-de-Sales and Musée Savoisien with lunch in between at a Savoyard restaurant. Unfortunately, the museum of the Château des Ducs de Savoie is closed on Mondays so we could not visit.

Morning

We had our usual breakfast in the morning at the InterContinental Lyon Hotel-Dieu. It was a bit of a late breakfast for as at 8:30am as we typically try to eat at opening time. We decided to visit Chambery today. Chambery is about an hour and a half away by direct train and was a former capital Savoy, which was ruled by the House of Savoy. In modern times, it is the prefecture of the department of Savoie, roughly equivalent to a county seat in the US. Although we have been to Haute Savoie to the north, it is our first time here.

We headed out at around 9am to take the tram over to Lyon Part-Dieu. We decided to cross over the Pont Wilson today.

The weather was overcast, although it could have been worse!

Chambery

We got to Chambery at roughly 11:20am and walked to the south from the station, Chambery Challes-les-Eaux, to reach the city’s historic center.

We passed over a small river, the Leysse, that runs below grade along the median of a major street in the city.

We walked by a large statue titled La Sasson. It was created to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the annexation of Savoie into France during the French Revolution in 1792. This didn’t last, although it was annexed again for good in 1860.

One block away, we saw what seemed to be a cast iron coat of arms. It appears to be a variation of the coat of arms of Chambery.

We walked one more block to reach the Fontaine des Éléphants (Fountain of Elephants). It was created to honor Count Benoît de Boigne and his military successes in the service of the Maratha Empire in the Indian subcontinent.

We continued on a bit past the fountain to reach the Cathedral of Saint Francis de Sales. By now, it was raining and we wanted to take the most direct route. Unfortunately, the road was blocked ahead by a construction vehicle and there did not seem to be any way to reach the front of the cathedral.

So, we had to backtrack.

There were elephant markers on the ground here!

The front of the cathedral was just around the corner from this courtyard.

Cathédrale Saint-François-de-Sales

We arrived at Place Métropole, the square in front of the Cathédrale Saint-François-de-Sales (Saint Francis de Sales Cathedral). There was a tree, probably a Christmas tree, in front along with a little red house. There is still more than a month to go before Christmas so its possible there will be more decorations later.

The cathedral was built in the 15th century, although at the time it was just a chapel. The modern entrance has decorative patterns on the ground. We don’t know what the year 1851 refers to here.

We went inside to take a look.

The interior was quite impressive! The interior makes heavy use of trompe-l’œil, the artistic style of painting that looks like it is three dimensional.

The second floor that can be seen here is entirely painted on, it is not there at all.

This small organ is real, the stone patterns behind it are not.

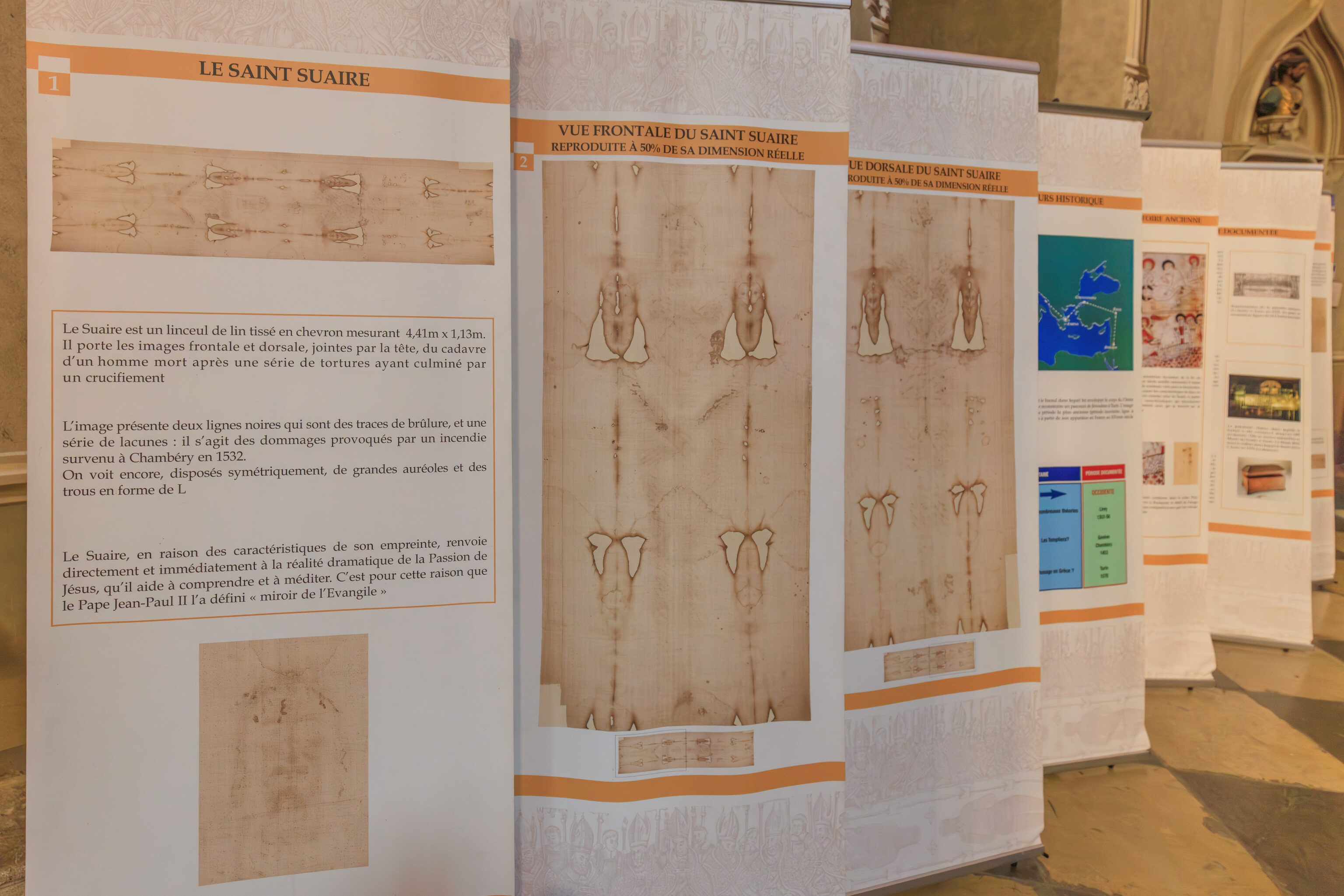

Its worth mentioning that this cathedral formerly held the Shroud of Turin. The signs above provide a description in French and also include photographs of both sides of the shround.

The Shroud of Turin is a linen cloth woven in a herringbone pattern, measuring 4.41m x 1.13m. It bears the frontal and dorsal images, joined at the head, of the corpse of a man who died after a series of tortures culminating in crucifixion.

The image shows two black lines, which are burn marks, and a series of gaps: these are the damage caused by a fire that occurred in Chambéry in 1532. Large halos and L-shaped holes can also be seen, arranged symmetrically.

The Shroud, because of the characteristics of its image, refers directly and immediately to the dramatic reality of the Passion of Jesus, which it helps us to understand and meditate upon. It is for this reason that Pope John Paul II defined it as a “mirror of the Gospel.”

Sign, translated using Google.

The shroud was purchased in the 15th century by the House of Savoy who kept it here. It was moved to Turin after the Savoys moved their capital to Turin. It is currently owned by the Catholic Church. The history of the shroud prior to the 14th century seems to be unclear.

We exited the cathedral when it closed at noon. There is a two hour break before it opens again at 2pm. We noticed after we exited that there are actually three little houses underneath the Christmas tree, each with a different design and color scheme.

We decided to go check out the Savoyard Museum next. We didn’t immediately realize that the entrance is at the northern corner of the square in front of the cathedral!

The museum actually closes at 12:30pm and reopens at 1:30pm. Oops! So, we decided to eat next.

We picked a restaurant a few blocks to the south. Getting there required taking an indirect path due to the old historic streets of the city. We passed by this outdoor public urinal that also seemed to double as a planter! This is definitely a European thing!

A typical street in the area.

We walked by the Charles Dullin Theatre, an Italian-style theatre built in 1866.

A smaller narrower street.

Lunch

It turns out that the restaurant we wanted to go to was closed. So, we decided to head over to Restaurant le Savoyard, not far to the west of this traffic circle.

(Mure, Péche, Cassis, Myrtille, Châtaigne, Framboise)”

We ordered a local variation of the Kir apératif.

We’ve had tartiflette before but never croziflette. It is similar to the tartiflette except it has pasta instead of potatoes. Both are Savoyard dishes from the local Savoy region.

It was unfortunately a bit blander than the tartiflette that we recall, perhaps due to it being purely Reblochon cheese?

Risotto aux girolles”

The fish was excellent. It was well cooked and had excellent flavor with the risotto. The actual fish was pretty bland by itself.

The croziflette came with some salad. It was salad.

After lunch, we backtracked to return to the Savoyard Museum.

Musée Savoisien

Entrance to the Musée Savoisien was free of charge, although you still do get a paper ticket.

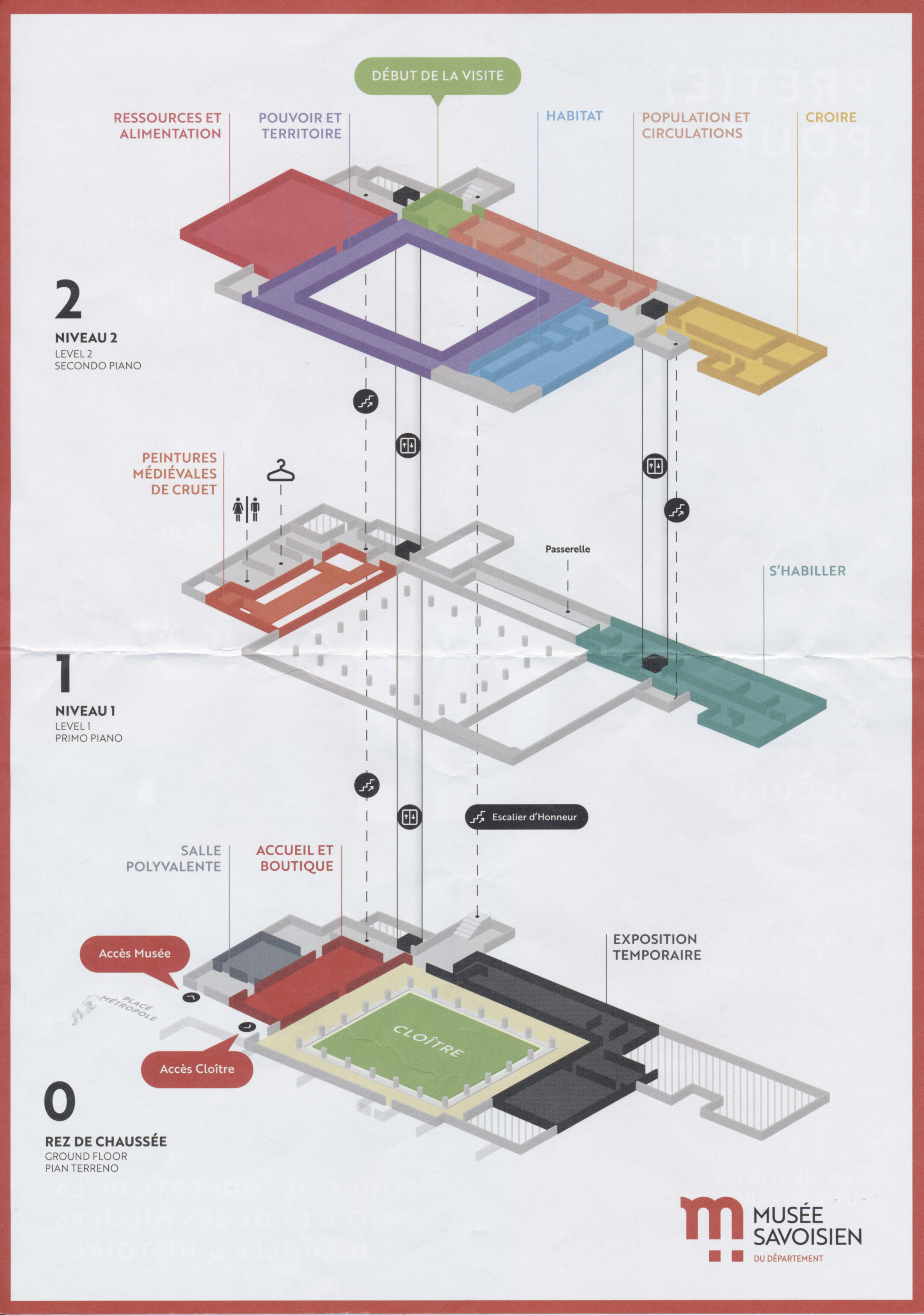

We also received a small map. The museum itself isn’t very large, although the way it is laid out it is easy to completely miss parts of it.

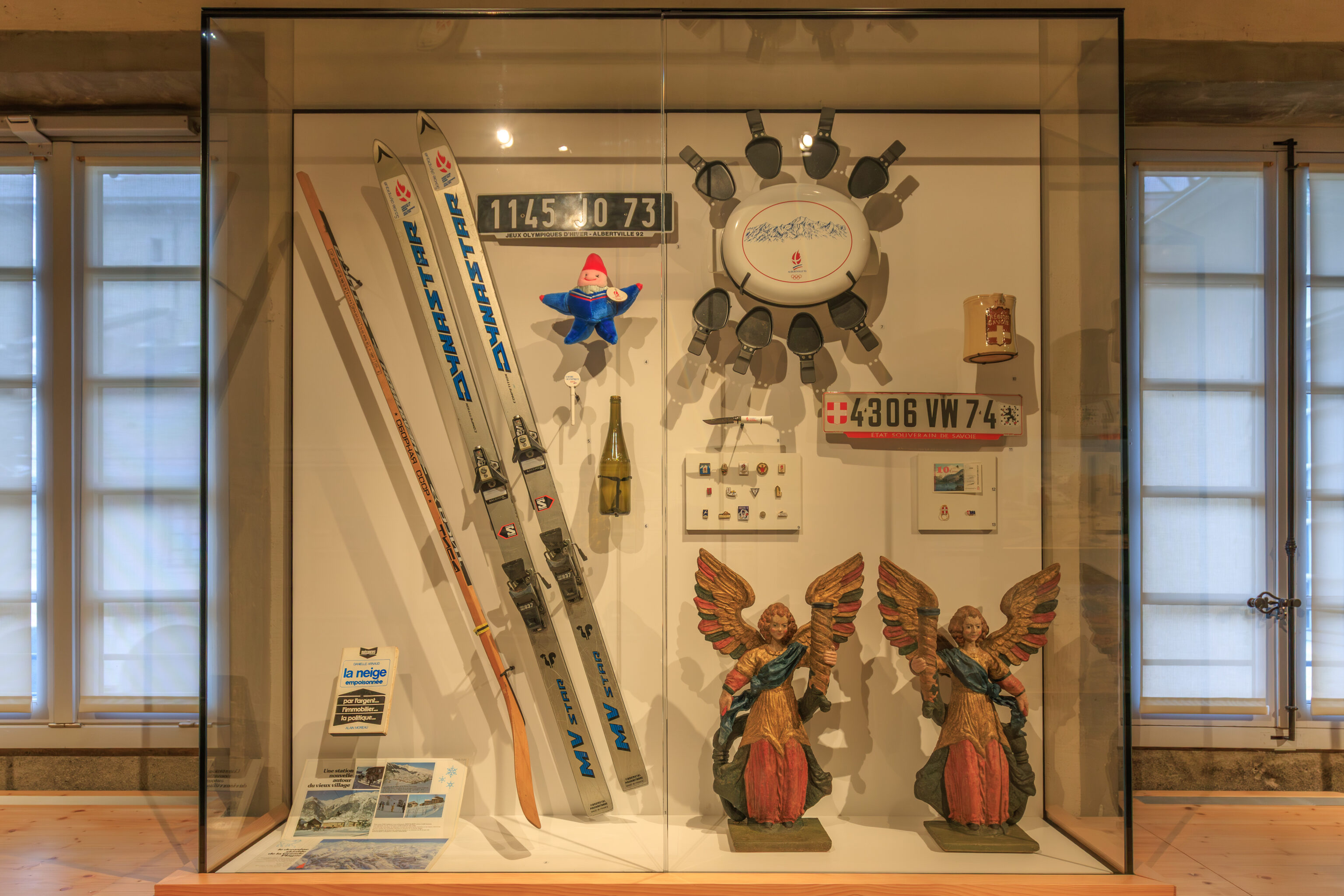

A few relatively modern artifacts from the region.

“Conjux-Le Port 3”

Late Bronze Age-812

Lake Bourget

Tact Workshop

based on excavation plans by Yves Billaud

Scale: 1/58

This village, covering 1500 m², is made up of buildings on stilts built on the bank of the lake. The houses, ranging from 25 to 70 m², consist of a single room divided in two by a row of posts. They are built of wood, earth, and plant materials. The stilts support beams, roofs, and walls and are joined by mortise and tenon joints as well as by knotted ropes.

(Translated using Google)

This model shows what a village would have looked like 2,800 years ago near Lake Bourget, a lake to the north of Chambery. It even has little sheep!

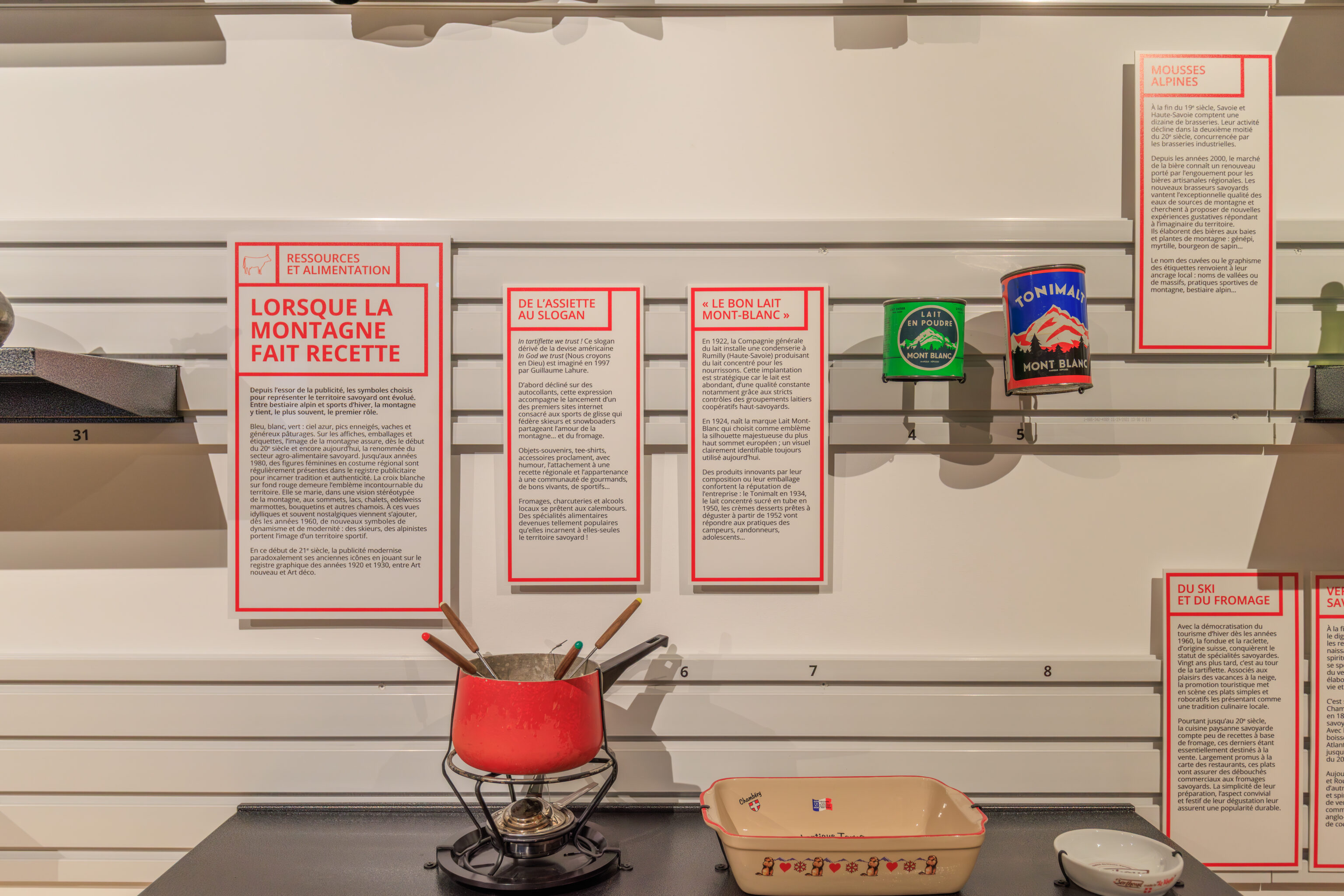

This large room contained a large three dimensional map of the region as well as many artifacts on display.

This boat was the subject of an exceptional archaeological operation. It lay at the bottom of Lake Bourget, at a depth of 32 meters, off the Pointe de l’Ardre (Brison-Saint-Innocent, Savoie). It was recovered by the Department of Underwater and Submarine Archaeological Research (DRASSM) in 2017. It is almost its original length.

This boat was carved, for fishing or transport, from a single oak trunk between 680 and 940 AD using hatchets and adzes. The notches at its preserved end suggest possible repairs.

It is one of the few boats from this period on public display.

(Translated using Google)

We actually started off in a room off to the side of the main central room on the top floor of the museum. We walked through the central room next. It presented a timeline of the Savoyard region, along with artifacts from the time period. There were also other rooms to explore from this main central room.

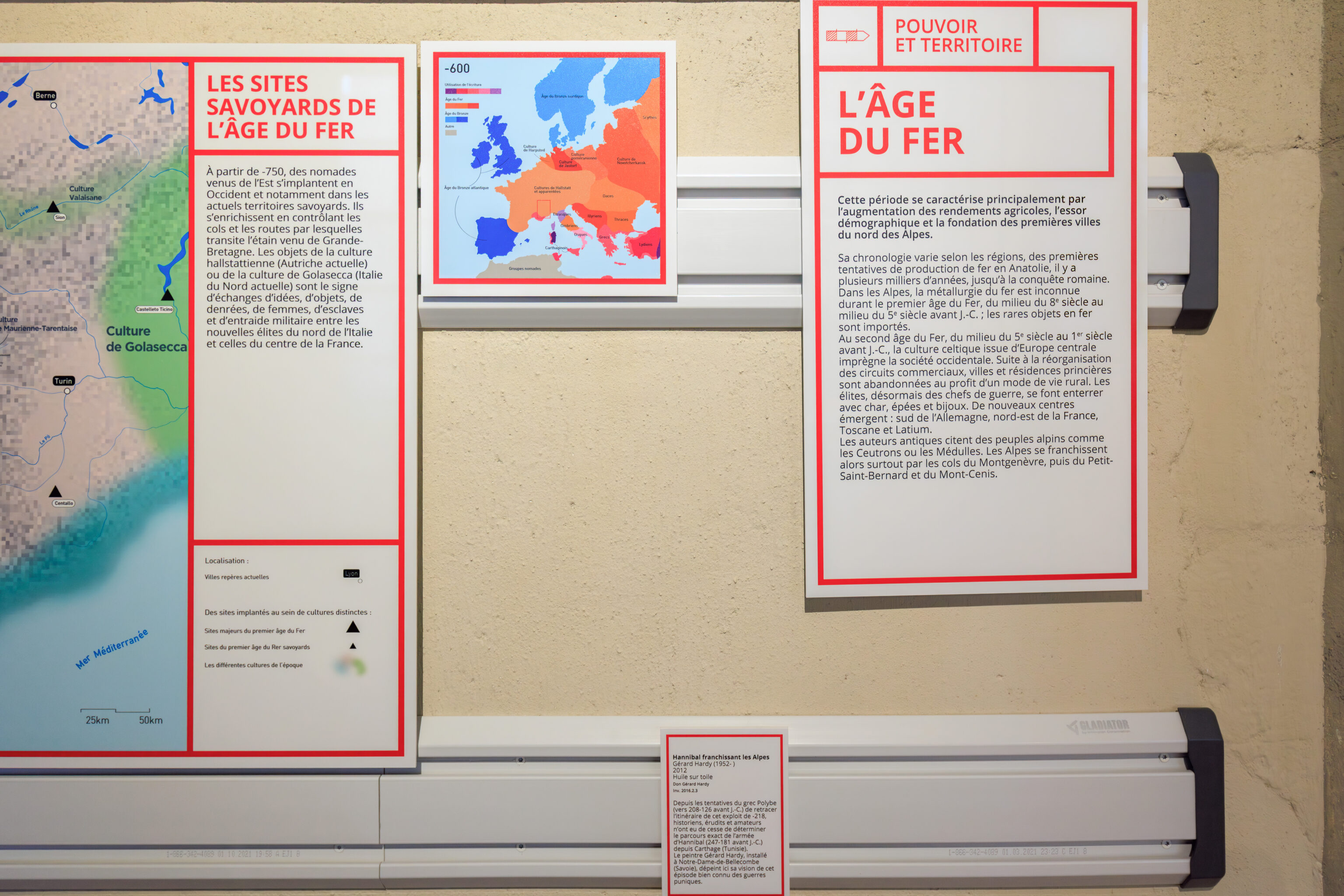

THE IRON AGE

This period is characterized primarily by increased agricultural yields, population growth, and the founding of the first cities north of the Alps. Its chronology varies by region, from the first attempts at iron production in Anatolia several thousand years ago to the Roman conquest. In the Alps, iron metallurgy was unknown during the Early Iron Age, from the mid-8th century to the mid-5th century BC; the few iron objects that existed were imported.

During the Late Iron Age, from the mid-5th century to the 1st century BC, Celtic culture from Central Europe permeated Western society. Following the reorganization of trade routes, cities and princely residences were abandoned in favor of a rural lifestyle. The elites, now warlords, were buried with chariots, swords, and jewelry. New centers emerged: southern Germany, northeastern France, Tuscany, and Latium.

Ancient authors mention Alpine peoples such as the Ceutrones and the Medulli. The Alps were then crossed primarily via the Montgenèvre Pass, then the Little St. Bernard Pass, and the Mont Cenis Pass.

SAVOYARD SITES OF THE IRON AGE

From 750 BC onwards, nomads from the East settled in the West, particularly in what is now Savoy. They grew wealthy by controlling the mountain passes and routes used to transport tin from Great Britain. Objects from the Hallstatt culture (present-day Austria) or the Golasecca culture (present-day Northern Italy) attest to the exchange of ideas, objects, goods, women, slaves, and military cooperation between the new elites of Northern Italy and those of Central France.

(Translated using Google)

Gérard Hardy (1952-)

2012

Oil on canvas

Gift of Gérard Hardy

Inv. 2016.2.3

Since the attempts of the Greek Polybius (c. 208-126 BC) to retrace the route of this feat of 218 BC, historians, scholars, and enthusiasts have tirelessly sought to determine the exact path of Hannibal‘s army (247-181 BC) from Carthage (Tunisia). The painter Gérard Hardy, based in Notre-Dame-de-Bellecombe (Savoie), depicts here his vision of this well-known episode of the Punic Wars.

This painting shows an artist painting the scene. Presumably, the artist is imagining himself here at this place creating this painting.

SAVOY IN THE MIDDLE AGES

The last king of Burgundy died in 1032, leaving Emperor Conrad II (1024-1039) a kingdom with weakened authority. The absence of the new overlord only increased the power of the bishops and strengthened the rise of new families such as the Guigonids in Dauphiné and the Humbertians in Savoy.

Humbert I (before 1000-1042) is the first known member of the House of Savoy. His descendants, Counts of Maurienne in 1146, then Counts of Savoy from 1196, finally became Dukes in 1416. The evolution of their possessions took place within a context of competing powers in the Northern Alps: those of the Pope and the Emperor, urban elites, and ecclesiastical and secular lords. Dauphiné, Milan, the Habsburg states, and France were powerful rivals with whom alliances and conflicts alternated. The Treaty of Paris of 1355 marked an important milestone: Amadeus VI, Count of Savoy (1343-1383), and John the Good, King of France (1350-1364), defined a border that would not be challenged. until the 16th century. Control of the mountain passes was a major issue for the House of Savoy, leading King Francis I of France (1515 1547) to nickname them “gatekeepers of the Alps.”

THE WESTERN ALPS FROM THE LATE 12TH CENTURY TO THE EARLY 14TH CENTURY

The decline of royal power after the death of Rudolph III, King of Burgundy (996-1032), resulted in the proliferation of places and forms of power. Bishops, abbots, and priors developed ecclesiastical lordships, while new families created secular lordships for their own benefit.

This map only very imperfectly reflects medieval reality, as the exercise of power was based on personal relationships and not on the delimitation of territories. It is in this context that the House of Savoy gradually asserted itself.

(Translated using Google)

Circa 1250

Sculpted and painted limestone

On deposit from the municipality of Le Bourget-du-Lac Listed as a historical monument by decree of August 23, 1900 These sculptures come from the wall separating the chancel from the nave of the church of Le Bourget, called the rood screen. They depicted the Annunciation to the Shepherds and the Nativity. The quality of these sculptures, inspired by both French art and the Po Valley, testifies to the political importance of this priory founded by Count Amadeus I (circa 1043-circa 1050).

+ Church of Le Bourget-du-Lac (Savoie)

(Translated using Google)

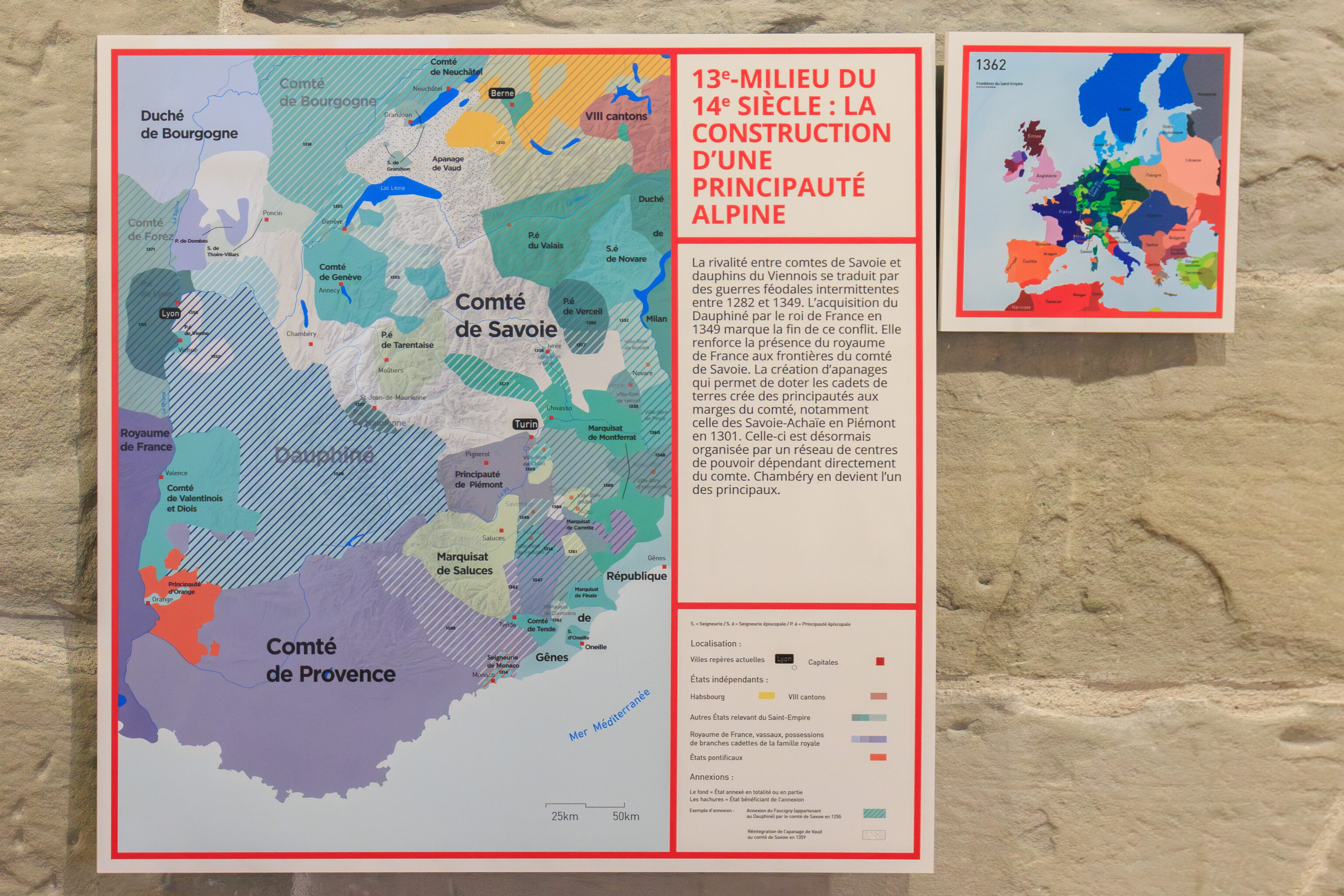

The rivalry between the Counts of Savoy and the Dauphins of Viennois resulted in intermittent feudal wars between 1282 and 1349. The acquisition of the Dauphiné by the King of France in 1349 marked the end of this conflict. It strengthened the presence of the Kingdom of France on the borders of the County of Savoy. The creation of appanages, which allowed younger sons to be endowed with land, created principalities on the margins of the county, notably that of Savoy-Achaea in Piedmont in 1301. This principality was now organized by a network of centers of power directly dependent on the Count. Chambéry became one of the main centers.

(Translated using Google)

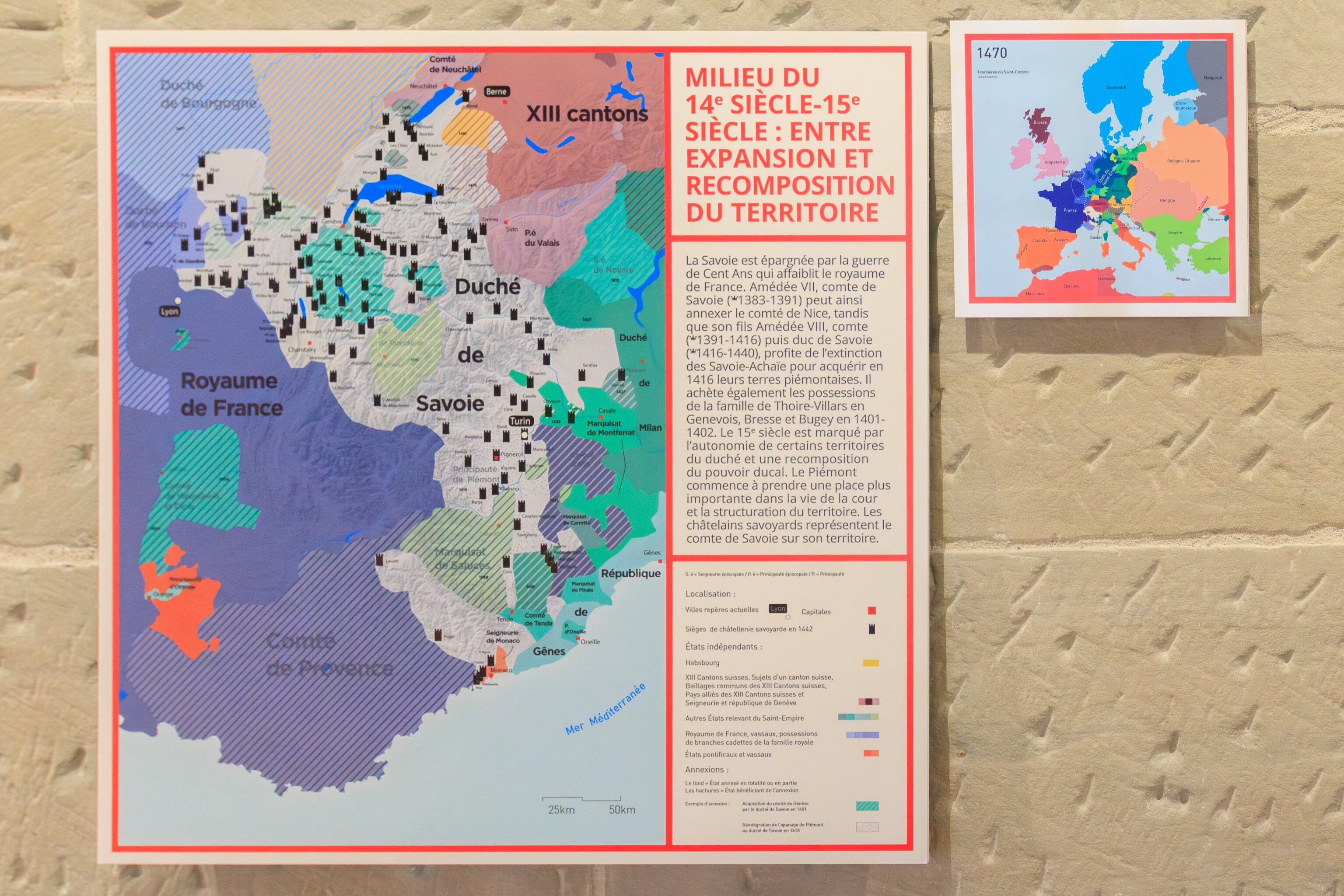

Savoy was spared by the Hundred Years’ War, which weakened the Kingdom of France. Amadeus VII, Count of Savoy (1383-1391), was thus able to annex the County of Nice, while his son, Amadeus VIII, Count (1391-1416) and later Duke of Savoy (1416-1440), took advantage of the extinction of the Savoy-Achaea line to acquire their Piedmontese lands in 1416. He also purchased the possessions of the Thoire-Villars family in the Genevois, Bresse, and Bugey regions in 1401-1402. The 15th century was marked by the autonomy of certain territories within the duchy and a restructuring of ducal power. Piedmont began to play a more significant role in court life and the structuring of the territory. The Savoyard castellans represented the Count of Savoy within his territory.

(Translated using Google)

17th century

Savoy

Oil on wood

On loan from the Museum of Fine Arts of the city of Chambéry

Until 1128, the Counts of Savoy were lay abbots of Saint-Maurice-d’Agaune and thus made Saint Maurice their patron saint. Then, the subsequent counts distanced themselves from the management of the abbey. The saint only regained an important place with Amadeus VI (1343-1383), and especially Amadeus VIII (1391-1440) who created the chivalric order of Saint Maurice.

+ Museum of Fine Arts of Chambéry (Savoy)

(Translated using Google)

This Saint Maurice is the same one that St. Moritz, Switzerland is named after.

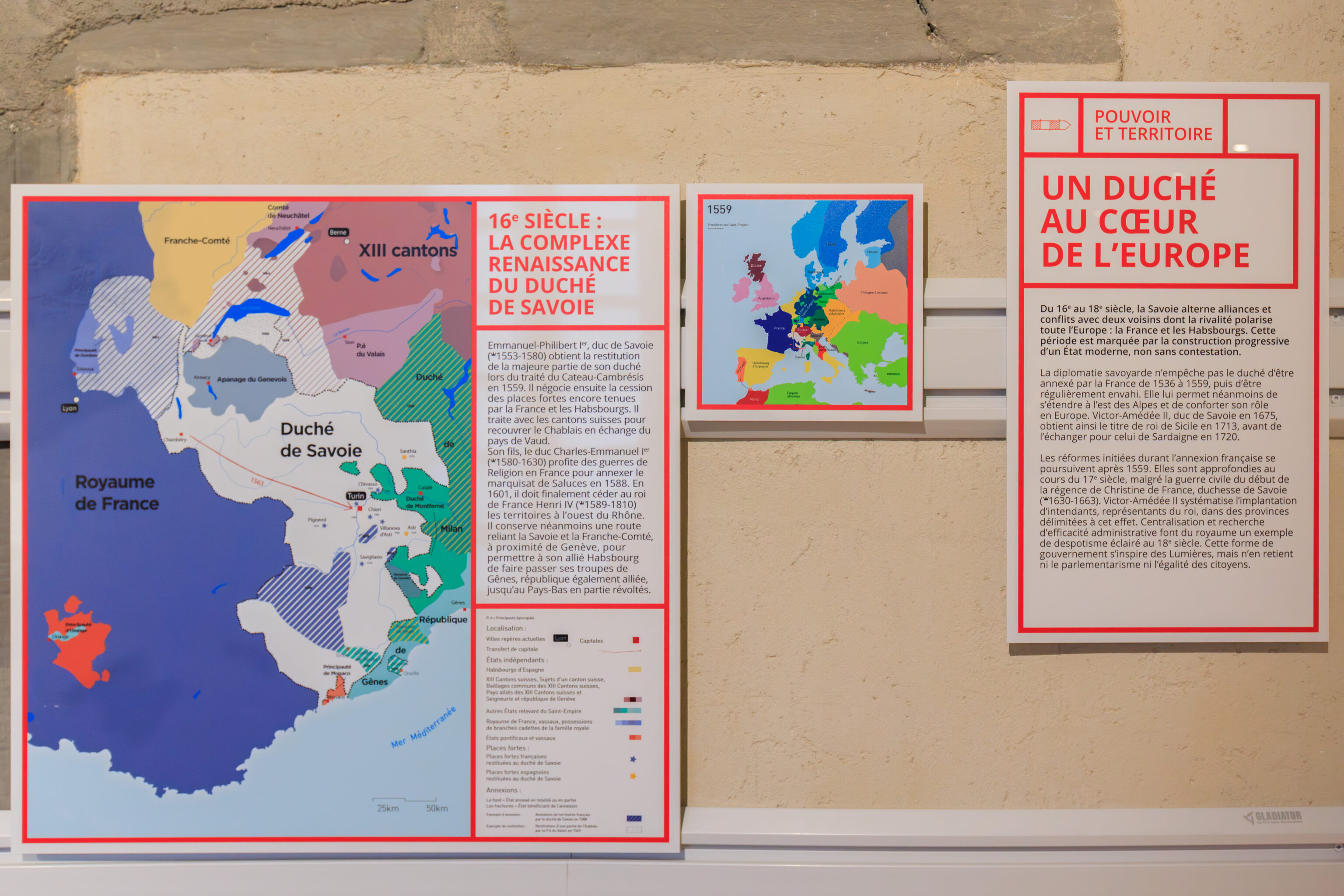

Emmanuel Philibert I, Duke of Savoy (1553-1580), obtained the return of most of his duchy in the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559. He then negotiated the cession of the strongholds still held by France and the Habsburgs. He dealt with the Swiss cantons to recover the Chablais region in exchange for the Pays de Vaud.

His son, Duke Charles Emmanuel I (1580-1630), took advantage of the Wars of Religion in France to annex the Marquisate of Saluzzo in 1588. In 1601, he was finally forced to cede to King Henry IV of France (1589-1810) the territories west of the Rhône. It nevertheless maintains a route linking Savoy and Franche-Comté, near Geneva, to allow its Habsburg ally to move its troops from Genoa, also an allied republic, to the Netherlands, which were partly in revolt.

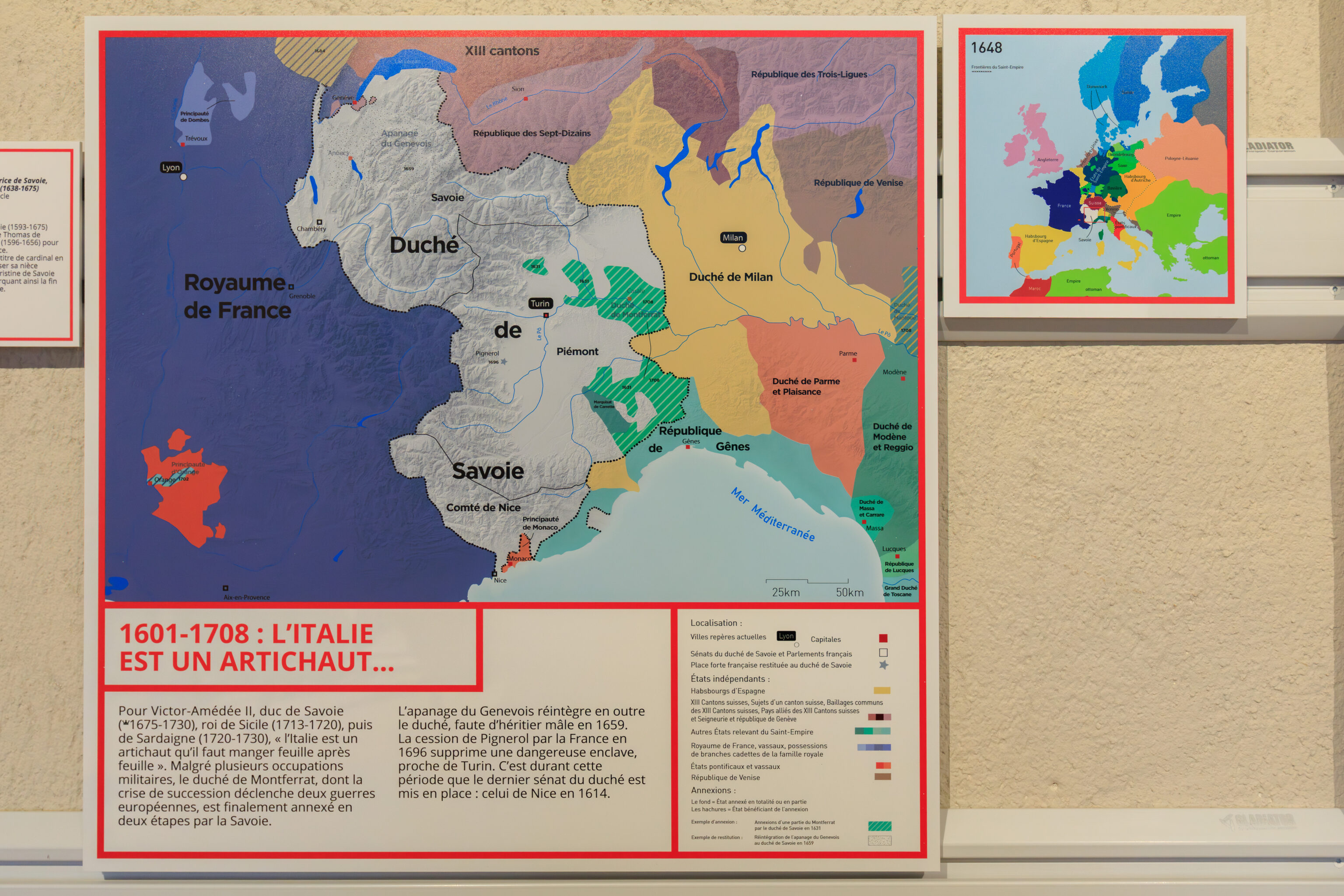

A DUCHY IN THE HEART OF EUROPE

From the 16th to the 18th century, Savoy alternated between alliances and conflicts with two neighbors whose rivalry polarized all of Europe: France and the Habsburgs. This period was marked by the gradual construction of a modern state, not without controversy.

Savoyard diplomacy did not prevent the duchy from being annexed by France from 1536 to 1559, and subsequently from being regularly invaded. Nevertheless, it allowed Savoy to expand east of the Alps and consolidate its role in Europe. Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy in 1675, thus obtained the title of King of Sicily in 1713, before exchanging it for that of Sardinia in 1720.

The reforms initiated during the French annexation continued after 1559. They were further developed during the 17th century, despite the civil war at the beginning of the regency of Christine of France, Duchess of Savoy (1630-1663). Victor Amadeus II systematized the establishment of intendants, the king’s representatives, in provinces specifically designated for this purpose. Centralization and the pursuit of administrative efficiency made the kingdom an example of enlightened despotism in the 18th century. This form of government was inspired by the Enlightenment, but retained neither its parliamentarism nor the equality of citizens.

(Translated using Google)

For Victor Amadeus II, Duke of Savoy (*1675-1730), King of Sicily (1713-1720), then of Sardinia (1720-1730), “Italy is an artichoke that must be eaten leaf by leaf.” Despite several military occupations, the Duchy of Montferrat, whose succession crisis triggered two European wars, was finally annexed in two stages by Savoy.

The appanage of the Genevois was also reintegrated into the duchy, due to the lack of a male heir in 1659. The cession of Pinerolo by France in 1696 eliminated a dangerous enclave near Turin. It was during this period that the last senate of the duchy was established: that of Nice in 1614.

(Translated using Google)

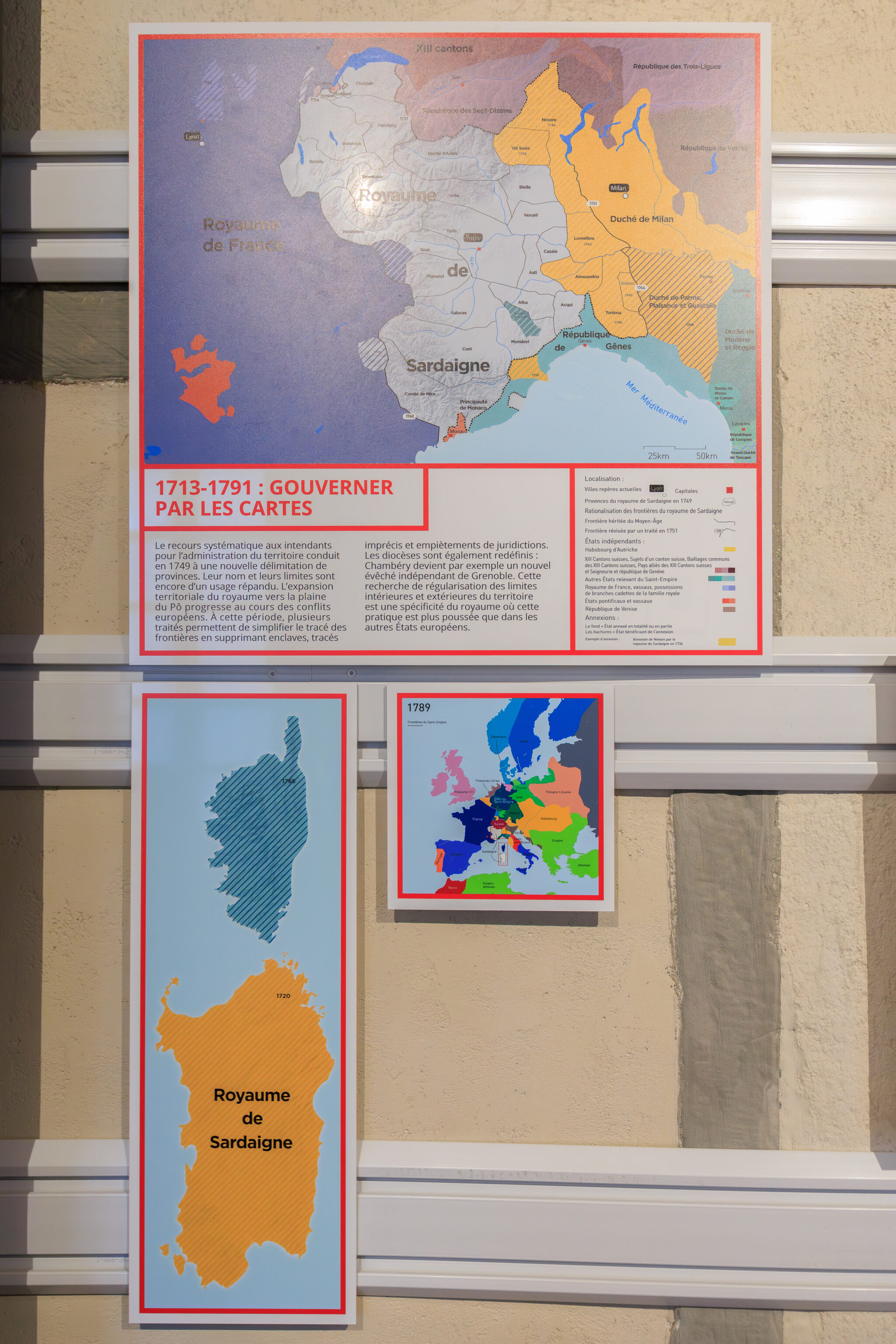

The systematic use of intendants for the administration of the territory led in 1749 to a new delimitation of provinces. Their names and boundaries are still in widespread use. The territorial expansion of the kingdom towards the Po Valley progressed during the European conflicts. During this period, several treaties simplified the drawing of the borders by eliminating enclaves, imprecise lines, and encroachments of jurisdiction. The dioceses were also redefined: Chambéry, for example, became a new diocese independent of Grenoble. This quest for regularization of the internal and external boundaries of the territory is a specific characteristic of the kingdom, where this practice was more developed than in other European states.

(Translated using Google)

THE RESTORATION OF SARDINIAN GOOD GOVERNMENT

With the fall of the First Empire in 1815, Victor Emmanuel I, King of Sardinia (1802-1821), recovered his entire kingdom. He pursued a policy of restoring the Ancien Régime, aiming to revoke all the reforms implemented during the French annexation.

This reactionary policy, often ironically referred to as Buon governo, good government, was comparable to that pursued in most European states. However, its implementation was incomplete: for example, not all national property was returned to the Catholic Church; those who had profited from the French annexation were not systematically prosecuted. In 1821, the Turin uprising, part of a broader European wave of liberal revolts, led to the king’s abdication. His brother Charles Felix succeeded him from 1821 to 1831, without any political change.

Charles Albert of Savoy, Prince of Carignan since 1800, inherited the throne of Sardinia in 1831. His education and his support for the First Empire raised hopes for a liberal shift. Until 1848, however, he maintained the same political system, while modernizing the justice system and the administration. He granted a degree of freedom to the press in 1847.

1815-1847: THE RESTORATION OF THE KINGDOM OF SARDINIA

The Treaty of Vienna of 1815, which established a new European order, allowed the Kingdom of Sardinia to annex the Republic of Genoa and the Canton of Geneva to regularize its borders in order to join the Swiss Confederation. The restoration proclaimed by King Victor Emmanuel I (1802-1821) was, however, accompanied by reforms.

In 1818, the new administrative organization was modeled on France: the departments were now replaced by divisions; the arrondissements by provinces. In 1847, the separate administration of the island of Sardinia ended, as it was fully integrated into the kingdom.

(Translated using Google)

THE KINGDOM AND NATION-STATE

The Risorgimento, meaning resurgence, refers to the movement for Italian unification. Its goal was to build a nation-state. It condemned the Kingdom of Sardinia —straddling the Alps and lacking linguistic unity— to disappearance.

King Charles Albert I (1831-1849) shifted his policies under the pressure of the European revolutions of 1848: he promulgated a liberal constitution, the Albertine Statute. He became militarily involved alongside the Italian insurgents against Austria. His defeat led him to abdicate in 1849 in favor of his son, King Victor Emmanuel II (1849-1878). The beginning of the latter’s reign was marked by the influence of his first minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour (1810-1861): anticlericalism, free trade, and the development of the railway contributed to the modernization of the kingdom.

In exchange for the support of Emperor Napoleon III (1852-1870) for the Risorgimento, the Plombières Agreement of 1858 stipulated the cession of Nice and the Savoy subject to a favorable plebiscite. The Franco-Sardinian victory against Austria in 1859 allowed Victor Emmanuel II to seize Lombardy and forced him to organize the plebiscite. The debates were heated, but the annexation prevailed.

1848-1860: SAVOY, NICE, AND ITALIAN UNIFICATION

France militarily supported the Kingdom of Sardinia in its war against Austria, which resulted in the annexation of Lombardy by the Treaty of Zurich in 1859. In return, the kingdom ceded Nice and Savoy to France. These formed the departments of Savoie, Haute-Savoie, and Alpes-Maritimes. Revolutions then broke out in most of the Italian states, leading to their annexation to the kingdom in 1860. The Expedition of the Thousand led to the annexation of Naples in 1861. Venetia was conquered in 1866 and Rome in 1870, completing Italian unification. The capital was transferred from Turin to Florence in 1864, and then to Rome in 1870. The Risorgimento led to the creation of a new European nation-state at the same time as the German Empire was also born.

(Translated using Google)

François-Barthélémy-Marius Abel

(1832-1870)

1860

Oil on canvas

This painting was created immediately after the annexation, in the hope that it would be purchased by Napoleon III in 1861. France, enthroned and crowned, extends her hand to welcome Savoy and Nice, depicted as young children. A young winged messenger carries the victorious tricolor banners of France and Italy.

(Translated using Google)

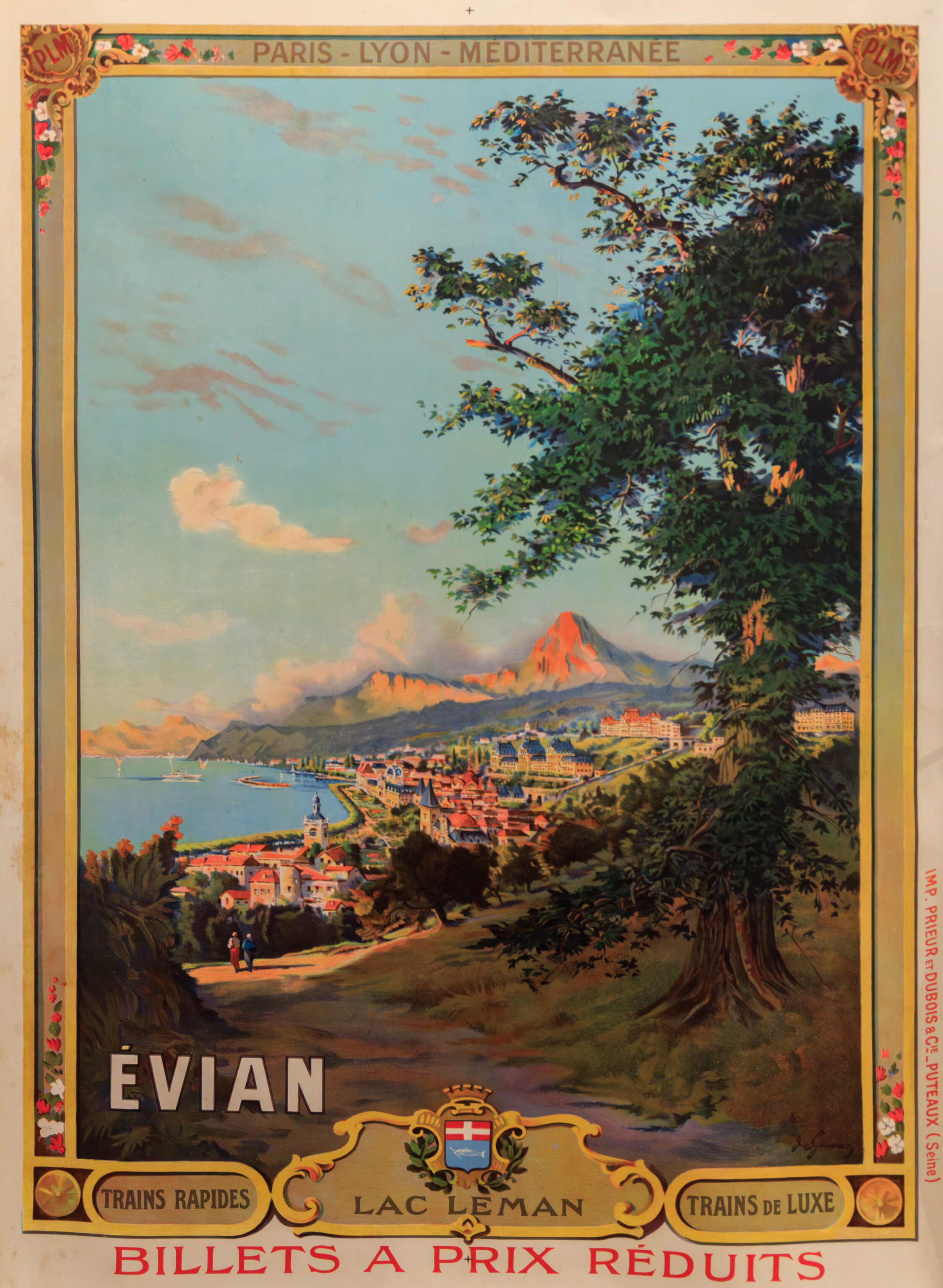

We’ve been to Evian!

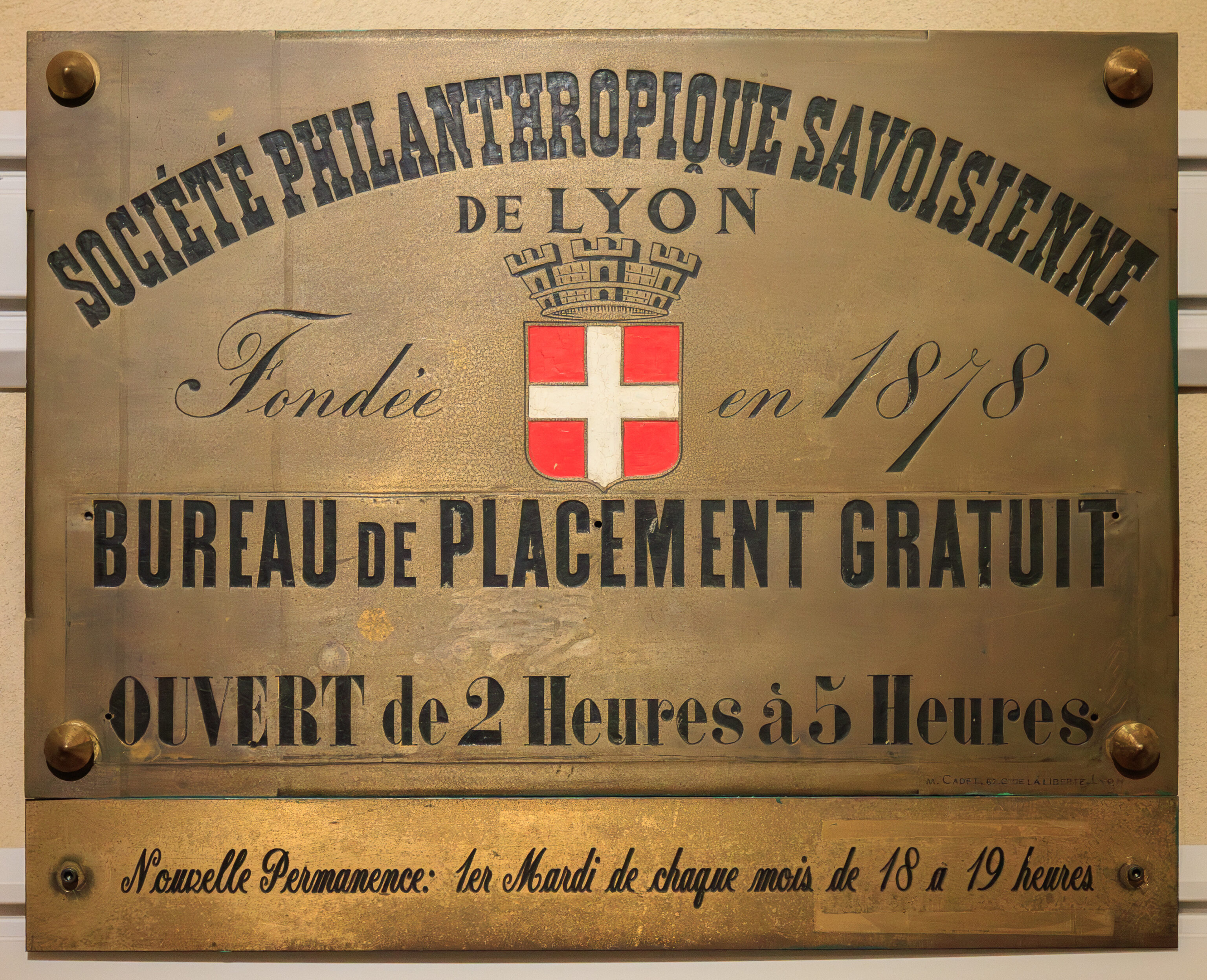

First half of the 20th century

Lyon

Enamelled metal

Gift of the Savoyard Philanthropic Society of Lyon

Inv.2022.12.1

The Savoyard Philanthropic Society of Lyon was originally a mutual aid society. This type of solidarity organization has been common since the mid-19th century, particularly for workers of the same geographical origin. Savoyard mutual aid societies often evolved into cultural associations. These associations are now present in Paris, Grenoble, the United Arab Emirates, and Canada.

(Translated using Google)

(Translated using Google)

The Kingdom of Sardinia was marked by great linguistic diversity in the 18th century. Numerous spoken languages were spoken there. The royal power employed others to administer its various territories. This great linguistic diversity was difficult to reconcile with the concept of the nation-state. Indeed, the idea of a nation rests in part on linguistic unity. This multilingual situation politically legitimized the disappearance of the kingdom in 1861.

In the French Alps, the chalet, a temporary dwelling used for farming and livestock farming, has become a symbol of mountain holidays.

At the end of the 18th century, the mountain was viewed with the chalet associated with poverty, purity, and innocence, as in Jean-Jacques Rousseau‘s (1712-1778) La Nouvelle Héloïse, published in 1761.

From a functional dwelling, it entered the realm of the imagination: in the 19th century, the wealthiest families used them to decorate their gardens. It became a widespread architectural type, both in spa and seaside resorts and on the outskirts of large cities. Switzerland, at the 1896 National Exhibition in Geneva, and then Savoy, at the 1937 Universal Exhibition in Paris, made it an emblem of the region.

The rise of winter sports, beginning in the early 20th century, gave the chalet a new lease on life. Noémie de Rothschild (1888-1968) commissioned the first ski chalet in Megève. This association between chalet and winter sports developed extensively during the 20th century, eventually becoming a global symbol. This collection of souvenir chalets bears witness to this.

Today, the image of the chalet is based as much on its ambiance and decor as on its architecture.

(Translated using Google)

The next section of the museum depicted what a ski chalet looks like inside.

THE SECOND WORLD WAR

The border location and topography of the two Savoyard departments placed them in a unique situation during the war.

In June 1940, fighting took place on the mountain passes during the attempted Italian invasion. Some border areas were occupied, but most of the territory remained in the Free Zone. The Vichy regime carried out its national revolution there: state-sponsored antisemitism, suspension of individual liberties, and the creation of the French Legion of Veterans. This policy provoked the first resistance movements and rescue efforts for Jews, facilitated by the proximity to Switzerland.

In 1942, Fascist Italy annexed the regions east of the Rhône. The fall of Benito Mussolini, head of government from 1922 to 1943, led to the Italian armistice of September 1943. Savoy and Haute-Savoie were then occupied by Nazi Germany until September 1944. The imposition of compulsory labor service encouraged enlistment in the Resistance. The Glières maquis (Haute-Savoie) in 1944 is the emblematic example of Savoyard Resistance movements. Liberation was preceded by Allied bombing raids, which notably affected Annecy, Chambéry, and Modane (Savoie).

1940-1947: THE TWO SAVOYARD DEPARTMENTS DURING WORLD WAR II

In 1940, only a few border towns were occupied by Fascist Italy, which also had a demilitarized corridor of fifty kilometers beyond the border. Nazi Germany occupied northern France as far as the Rhône River. In 1942, the Italian occupation extended beyond the Rhône, following the abolition of the Free Zone, which was now integrated into the German-occupied zone. The collapse of Mussolini’s regime in 1943 led to the occupation of the territory by Nazi Germany until the Liberation in 1944. The 1947 Treaty of Paris made some minor changes to the Franco-Italian border, to France’s advantage.

(Google Translated)

This room contained portraits of the House of Savoy.

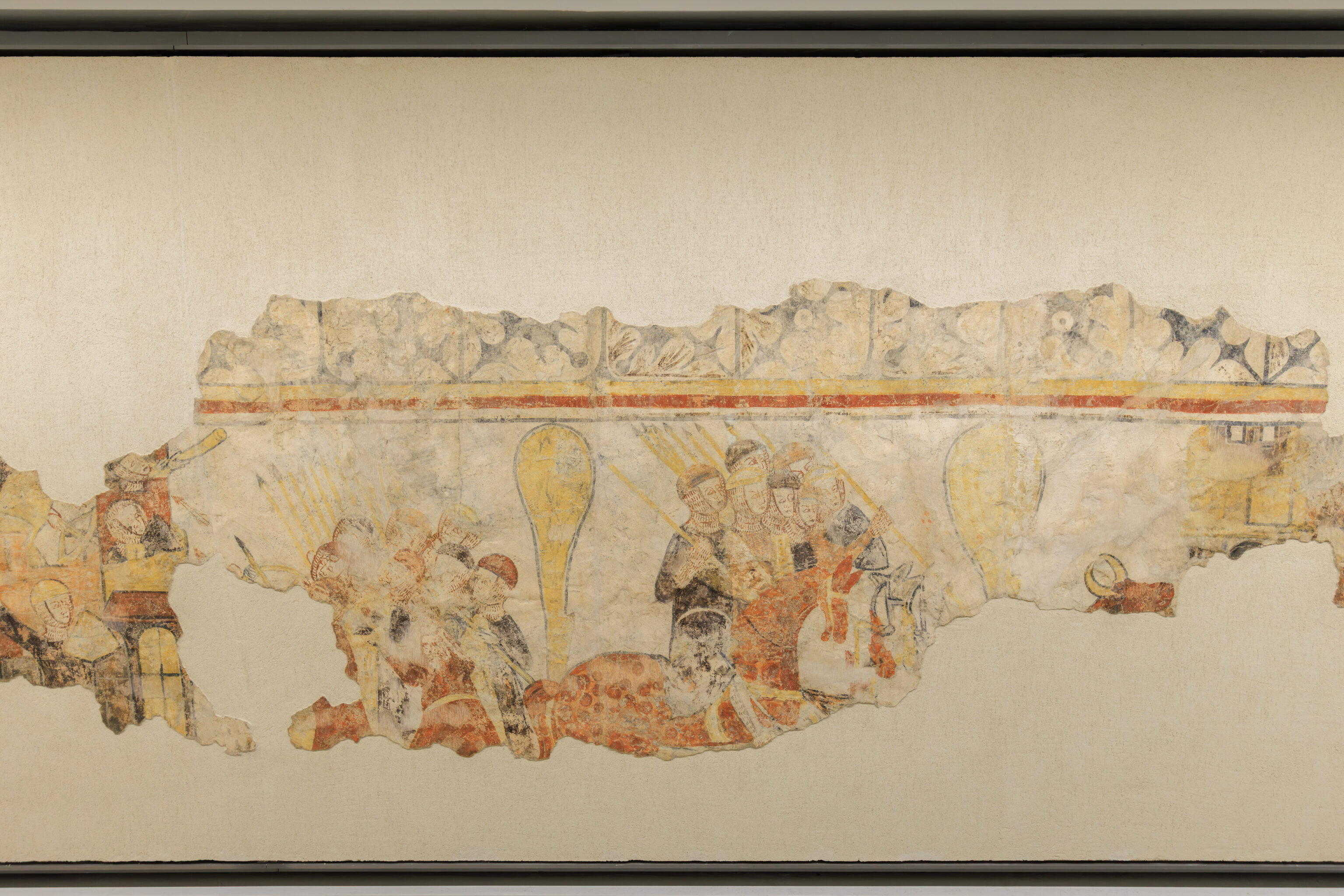

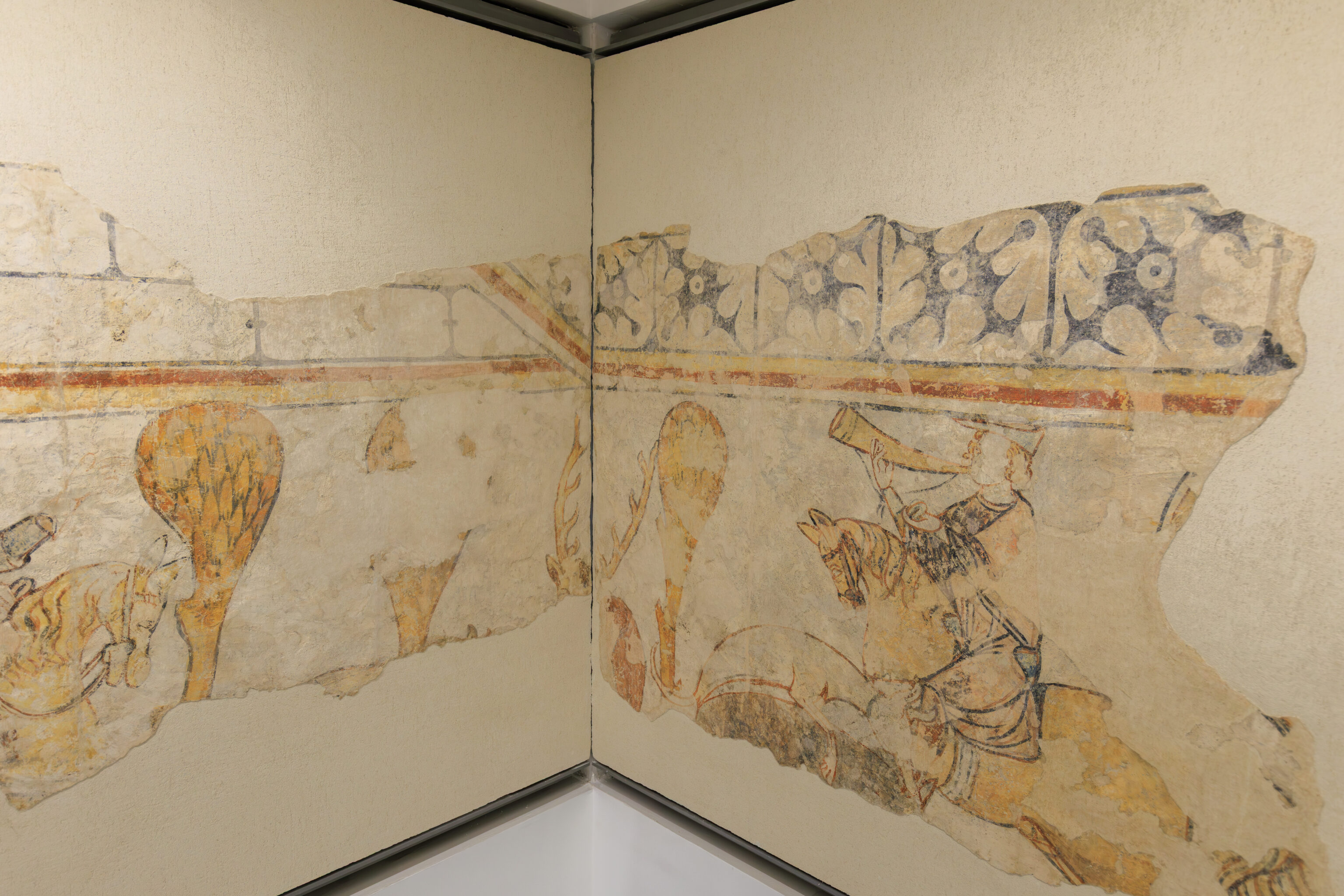

This room, overlooking the entrance lobby below, contains fragments of the Murals of Cruet. These paintings from the 14th century were discovered in 1985 at the Château de la Rive in Cruet, a few miles to the east of here. The placement of these murals above the room below is supposed to reflect the location where they were discovered.

Jacket, sweater, pants, hat, gloves, goggles, skis and poles

2007-2015

Synthetic material, plastic, metal

Donated by Michel Dietlin

This ski outfit from the French Ski School (ESF) in Courchevel 1550 was donated to the museum by Michel Dietlin, an alpine ski instructor for nearly forty years. These professional garments, similar for all instructors on the slopes, are chosen for their technical characteristics: warmth, flexibility, and waterproofing. Designed by leading brands, they take into account technical advancements in textiles, instructor feedback, while also following fashion trends.

Alpine skiing and snowshoeing outfit

Overalls, base layer, anorak, gloves, and hat

Cotton, synthetic material, plastic, metal

Donated by Anne-France Mailly

Anne-France Mailly, originally from Paris, but with parents who were mountain sports enthusiasts, started ski touring at the age of 10. Used between 1980 and 2000, this outfit perfectly illustrates the history of mountain clothing. Originally worn with a green and purple anorak, which coordinated with the gloves and hat. Anne-France later wore it with this red down jacket, which had become too small for her daughter.

Hiking outfit

Windbreaker, pants, t-shirt, socks, and shoes

Cotton, synthetic material, plastic, metal

Gabrielle Michaux

Born in Valence in the early 1970s and arriving in Savoie at the age of 10, Gabrielle Michaux mainly hikes on a day basis – in the Bauges, Vanoise, Chartreuse, and Belledonne mountain ranges – with her family and through scouting during her teenage years. As an adult, she enjoys multi-day hikes and guided treks. This outfit was used in the 1990s and 2000s for hiking in the mid-mountain range.

(Translated using Google)

We almost missed this section of the museum. We reached it by walking through a long corridor, although there was a more direct path through one of the rooms that we had visited already.

This display is interesting as it shows mountain sport clothing used by regular people.

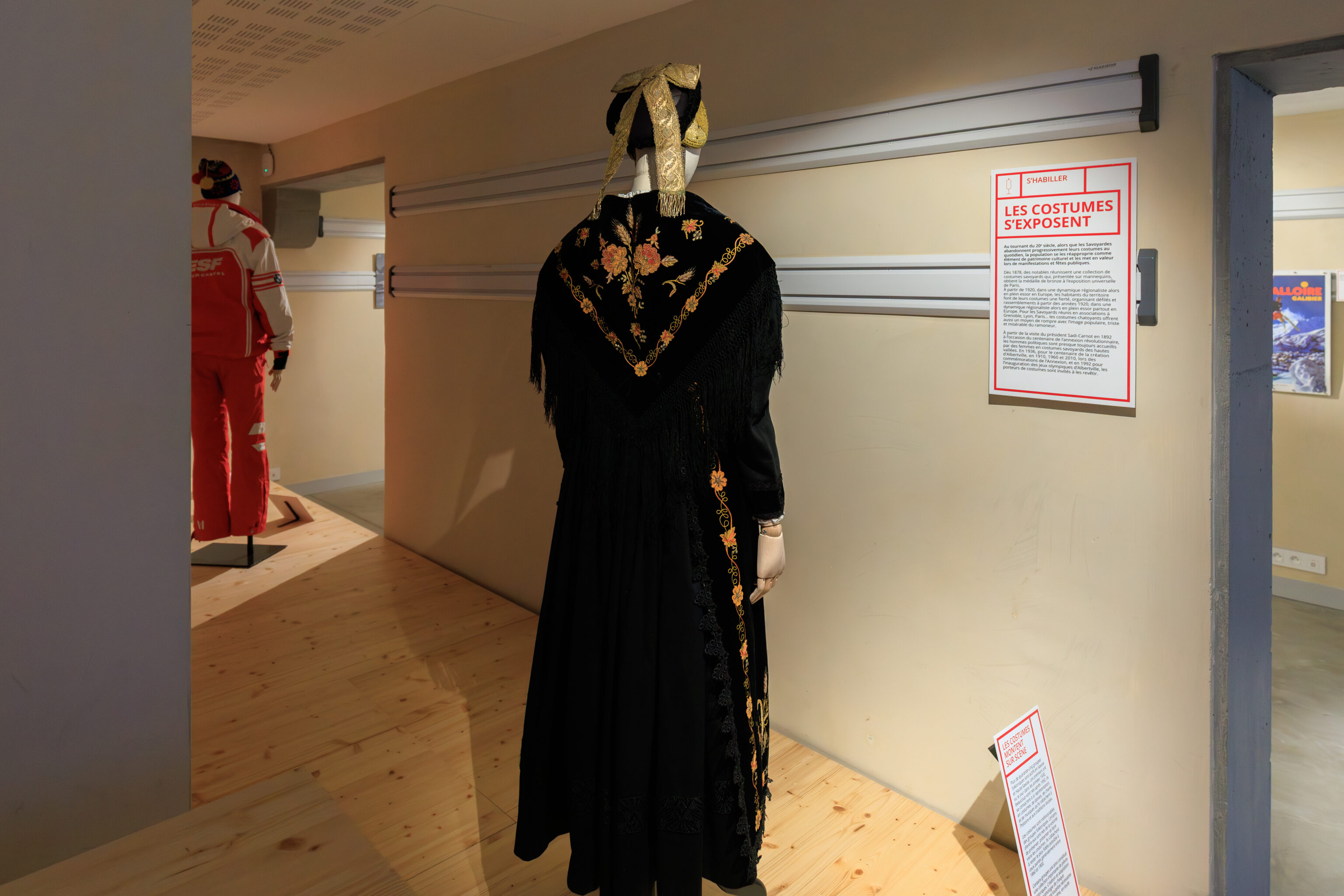

Dress, shawl, apron, belt

Second half of the 20th century

Saint-Colomban-des-Villards, Savoie

Wool, linen, silk, metal

(Translated using Google)

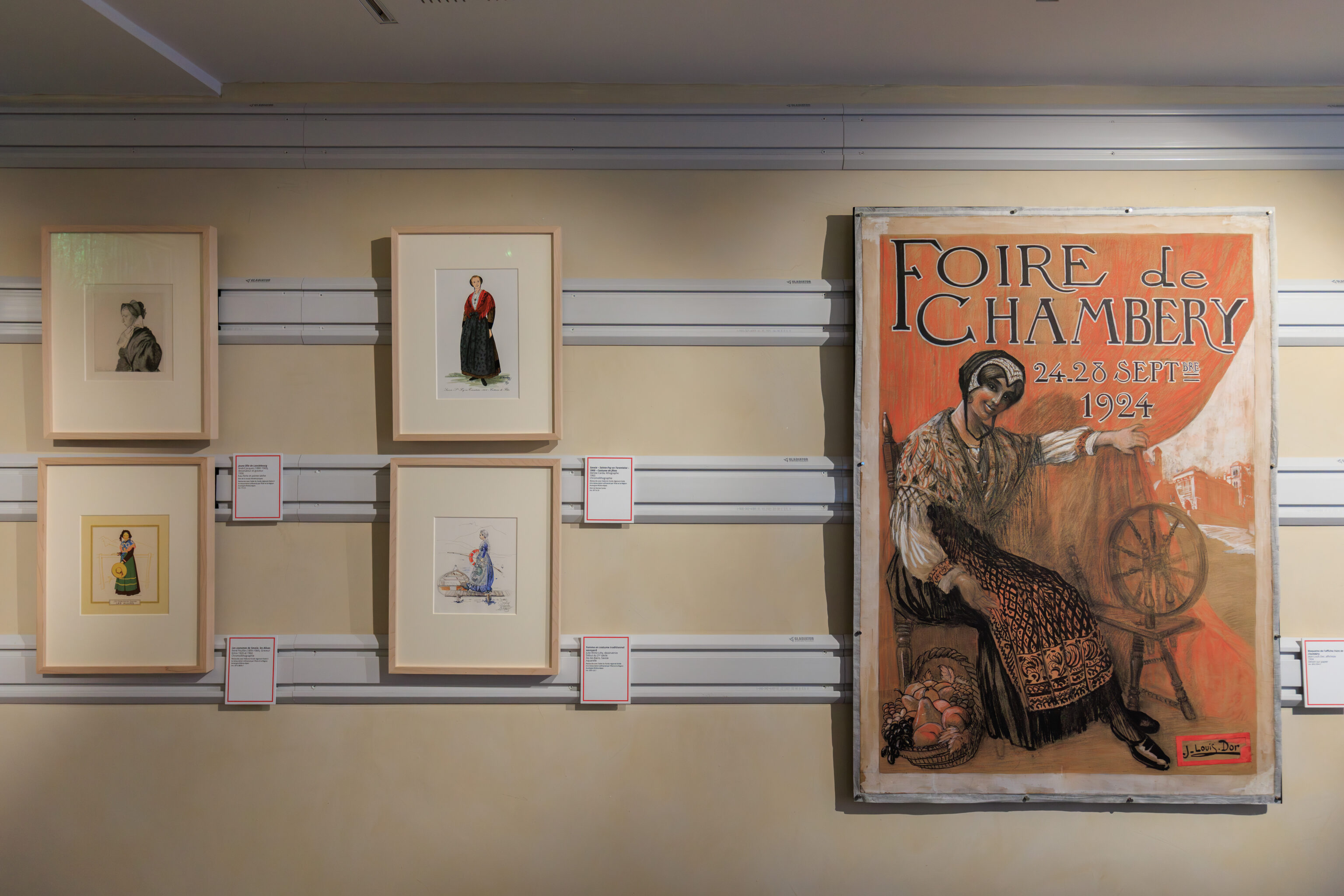

AND THE COSTUME WAS!

Under the gaze of urban elites and artists, costumes became standardized from the 19th century onward.

In the 17th century, clothing was known through descriptions in marriage contracts and post-mortem inventories. 18th-century paintings, drawings, and prints depict a diverse fashion where clothing reflected the wearer’s social status, gradually associating it with a specific region.

In the 19th century, travelers, intellectuals, and artists took a growing interest in Alpine populations. Between scientific discovery and the beginnings of tourism, they were fascinated by the contrast between their harsh daily lives and the beauty of their colorful festive attire. This outsider’s perspective contributed to the changing status of these garments: magnified and idealized by these representations, they became regional costumes. The publication of books and postcards widely disseminates their image and contributes to its preservation.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the emergence of new European states led political powers to recognize regional identities as a component of national identity. The display of regional costumes was then encouraged.

(Translated using Google)

Reconstruction based on the murals of Cruet (circa 1300)

Design by Nadège Gauffre-Fayolle, dyeing by Marie Marquet, sewing by Isolde Kovalitchouk

2014-2015

Wool, silk, linen, metal

Costume of the Empress

Reconstruction based on the murals of Cruet (circa 1300)

Design by Nadège Gauffre-Fayolle, dyeing by Marie Marquet, sewing by Isolde Kovalitchouk

2014-2015

Wool, silk, linen, metal

(Translated using Google)

Early 20th century

Sainte-Foy-Tarentaise, Savoie

Silk, wool, cotton

Loan from Françoise Gonguet

This velvet shawl and apron set, called a “wedding dress,” is embroidered with motifs—leaves, bunches of grapes, ears of wheat, and wild roses—in silk and gold thread. The headdress, or “frontière,” made of cardboard covered in velvet and trimmed with gold thread, is attached to the hairstyle, “couèche,” braids of hair covered with a black velvet ribbon, gathered into inverted and overlapping crowns. The “cordettes,” knots on the hairstyle, serve as the identity card of the women who wear them.

(Translated using Google)

The Savoyard Museum has been open since 1913. However, the site dates back to the 13th century when it was a Franciscan convent.

We walked around this central courtyard, perhaps more correctly a cloister.

Late Afternoon

After leaving the Savoyard Museum, we decided to head over to the Château des Ducs de Savoie. We had this view of the cathedral behind us as we walked away to the west.

We walked past a fountain at the Place Saint-Léger, about half way to our destination.

This is, unfortunately, a technically poor photo due to camera shake. Modern AI photo sharpening has cleaned it up a bit but its still rough when closely inspected. It is the only one we took with this fountain so here it is!

The square is more of a long wide mostly pedestrian street than an actual public square.

Some of these photos unfortunately also suffered from camera shake. If I recall, this was due to optical image stabilization accidentally being turned off on the lens. Luckily, the magic of modern software fixed these up nicely.

We proceeded down a side street and then ended up walking through this rather dark and uninviting passageway. Probably not a place we’d choose to walk through in the average American city.

We then walked through what is probably best described as a small residential courtyard. There are some interesting tiny windows in front of us here.

We continued on…

Château des ducs de Savoie

We ended up behind and below the Château des ducs de Savoie.

We walked to the east to try and find an entrance.

We found some stairs and a statue. The statue depicts the local Maistre brothers, Joseph and Xavier. Although the stairs were completely covered in leaves, we it seemed like a promising path and so we walked up to take a look.

First a stronghold, then a royal palace, the castle was the seat of power and administration for the counts and dukes of Savoy that drove the rapid expansion of the town of Chambery. It includes a remarkable set of buildings constructed in the 14th century till today, one of wich is the Holy Chapel wich held at the end of the Middle Ages the Holy Shroud relic. The castle houses the Prefecture and the Savoie Council since it became a part of France in 1860.

We found a very useful sign with a map. And, an opening schedule. The castle’s museum is open every day of the week except Monday. Today is a Monday. Oops!

This seems to be where we’d enter if the museum was open. The chateau is described as the prefecture for the department of Savoie. In this context, prefecture seems to refer to the building as the primary administrative facility for the department of Savoie.

We decided to try to go to the other side of the chateau to see if we could get a better view of the building. We ended up going down the leaf covered stairs to loop clockwise around the building.

This was the best view we were able to get, from across the street to the south.

We decided to start heading back to the train station to return to Lyon. It turns out that this street was actually the proper street to walk down to reach the stairs that we ascended earlier. We had walked by this street when we were at the Place Saint-Léger earlier.

We walked more or less directly to the north to get back to the station.

We ended up having to go upstairs to get to the platform for the train to Lyon. The station building was surprisingly large inside.

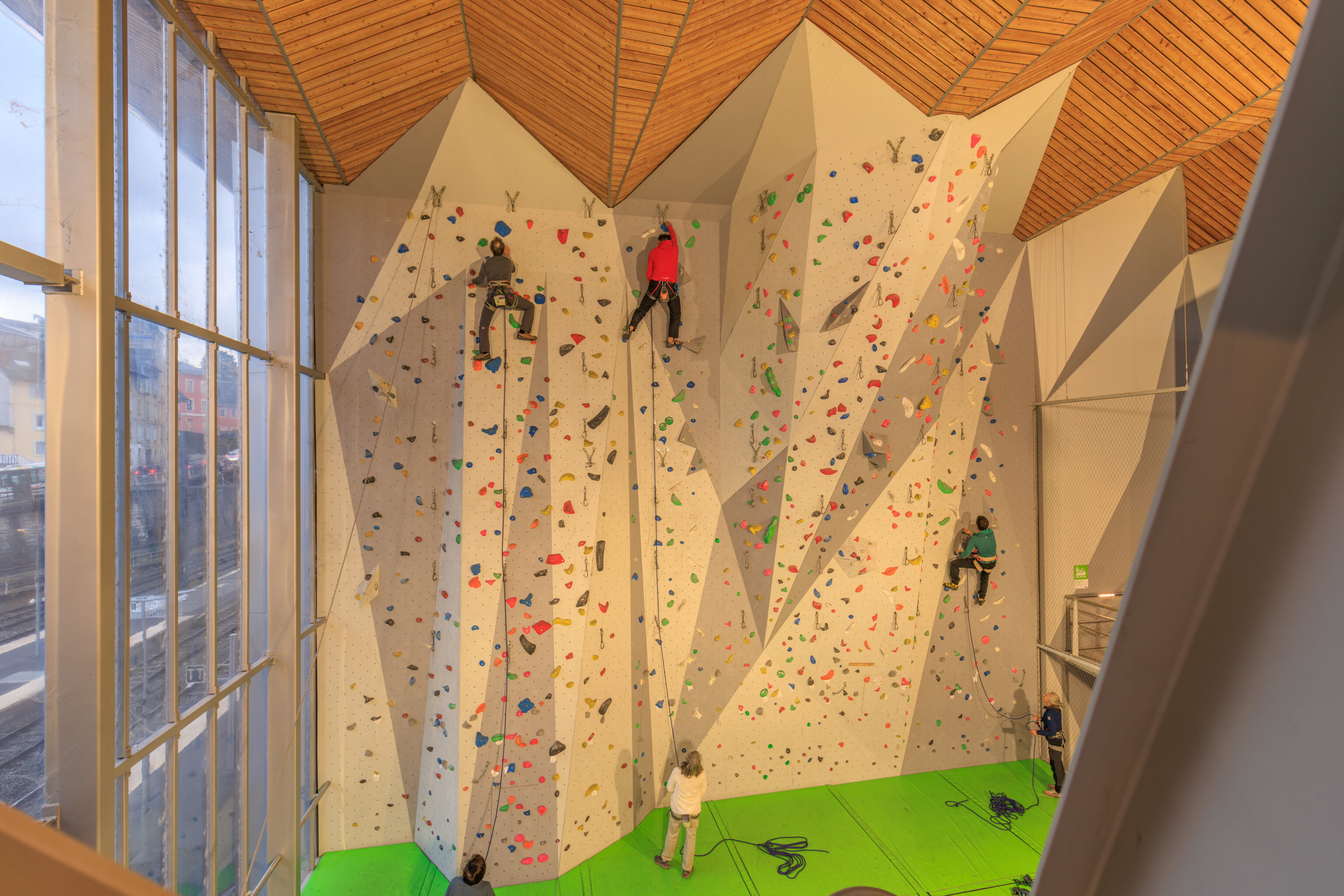

It even had a climbing wall! That’s definitely something we’ve never seen in a train station!

Otherwise, the station is just a typical multiple platform train station.

Lyon

Boisson onctueuse mangue coco avec perles de tapioca et perles de mangue, l’équilibre parfait entre la coco et la mangue.”

After returning to Lyon, we decided we wanted to get a bit of a snack. We didn’t feel hungry enough for a full dinner. We visited Fuwa Fuwa, a shop on Rue Victor Hugo about half way in between Place Bellecour and the Lyon-Perrache train station. It seems to be a mostly Japanese inspired snack shop with Taiwanese bubble tea and Korean bingsoo. The staff all wear cat ears!

We intended to get both bubble tea and bingsoo but it turns out that bingsoo wasn’t available. They explained something in French that we didn’t fully understand. We ended up just getting a bubble tea inspired drink.

The drink was pretty good. It’s unfortunate we could try their mango bingsoo. We realized when we left that we were their last customers of the day as they close at 7pm so maybe that’s why they couldn’t make bingsoo.

We still wanted to get a bit of actual food. There doesn’t seem to really be any good quick French options like there would be during breakfast or lunch at a boulangerie. So, we decided to try the Five Guys near the InterContinental. Five Guys has expanded quite a bit globally and is all over the place in Europe these days.

Overall, it was pretty similar to having Five Guys in the US. The burger tasted pretty similar and the fries were similar as well. The potatoes for the fries were from the Netherlands and the Heinz ketchup was made in the UK. The overall restaurant decor was identical to what you’d expect in the US. Overall, it was very American!