After breakfast at the Grande Bretagne, we visited the Acropolis Museum where we spent the entire morning. After lunch nearby, we visited the Areopagus, the hill closest to the Acropolis. We then walked back to the Grande Bretagne where we had dinner at GB Roof Garden.

Monday, April 21st, 2025

Today is our last full day in Athens! The only concrete plan we have for today is to visit the Acropolis Museum as we have timed entry tickets for the 9am to 10am time slot. We do also have reservations at the GB Roof Garden restaurant at the hotel, though it’s for well after our usual dinner time and won’t possibly interfere with anything we decided to do during the day.

Morning

As usual, after waking up at the Grande Bretagne, we had breakfast at the GB Roof Garden. Although we often need to check out early on the last day of a trip, we won’t need to tomorrow so we’ll have one more breakfast tomorrow. Today, we got the usual items from the buffet and also ordered a Croque Madame again.

It looks like it will be a beautiful day again here in Athens!

Acropolis Museum

We headed to the Acropolis Museum via Metro, taking it one stop from the Syntagma station to the Acropolis station.

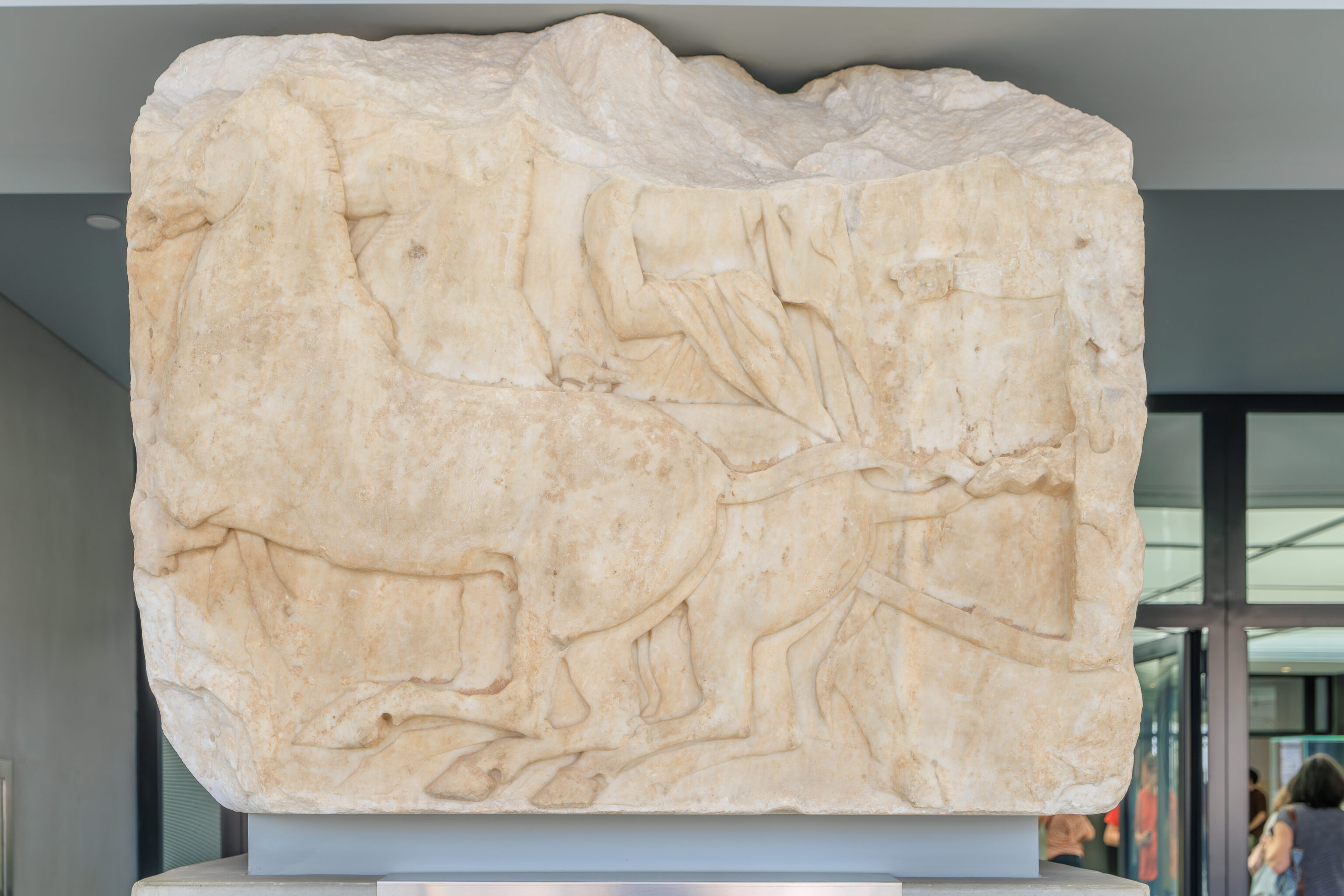

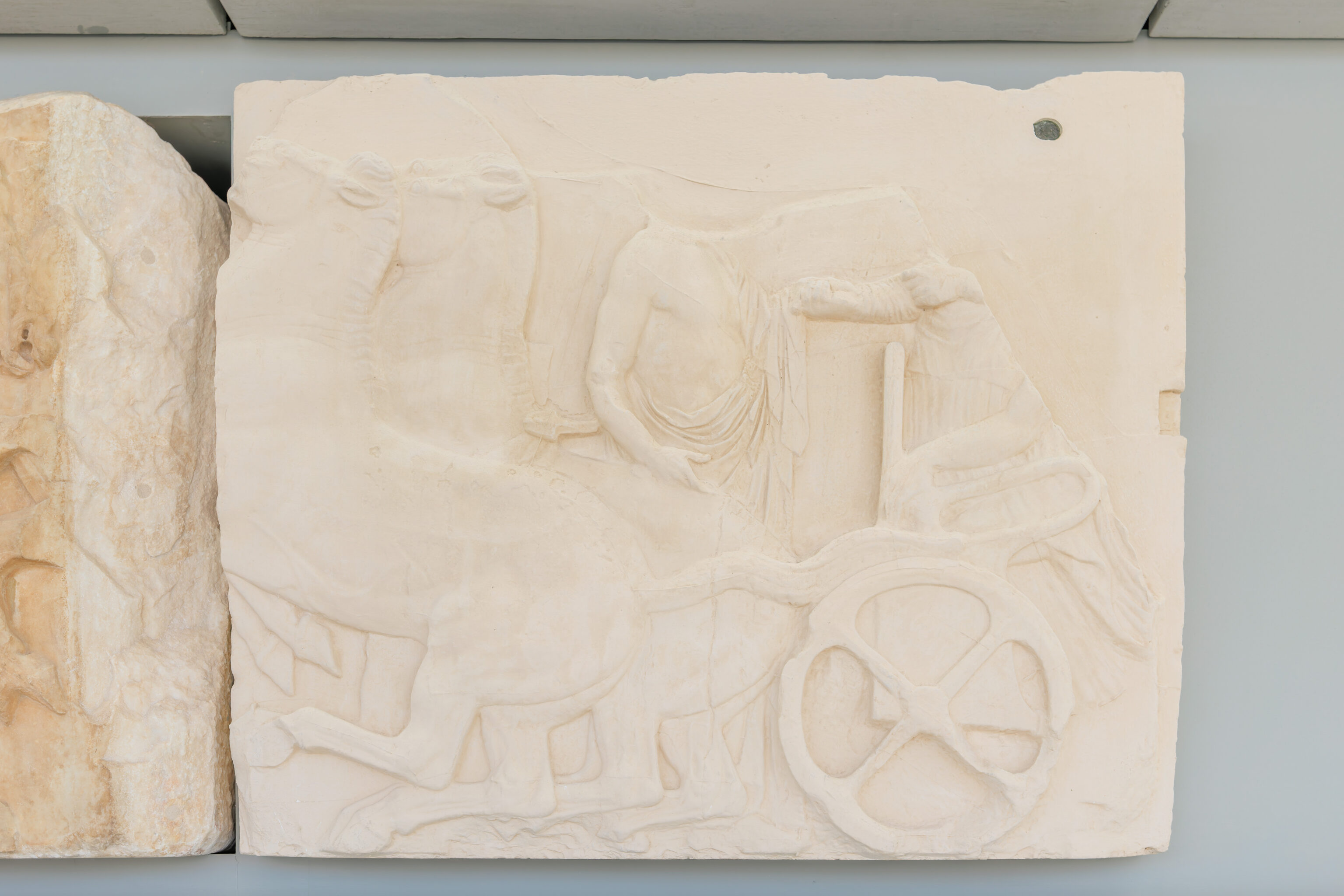

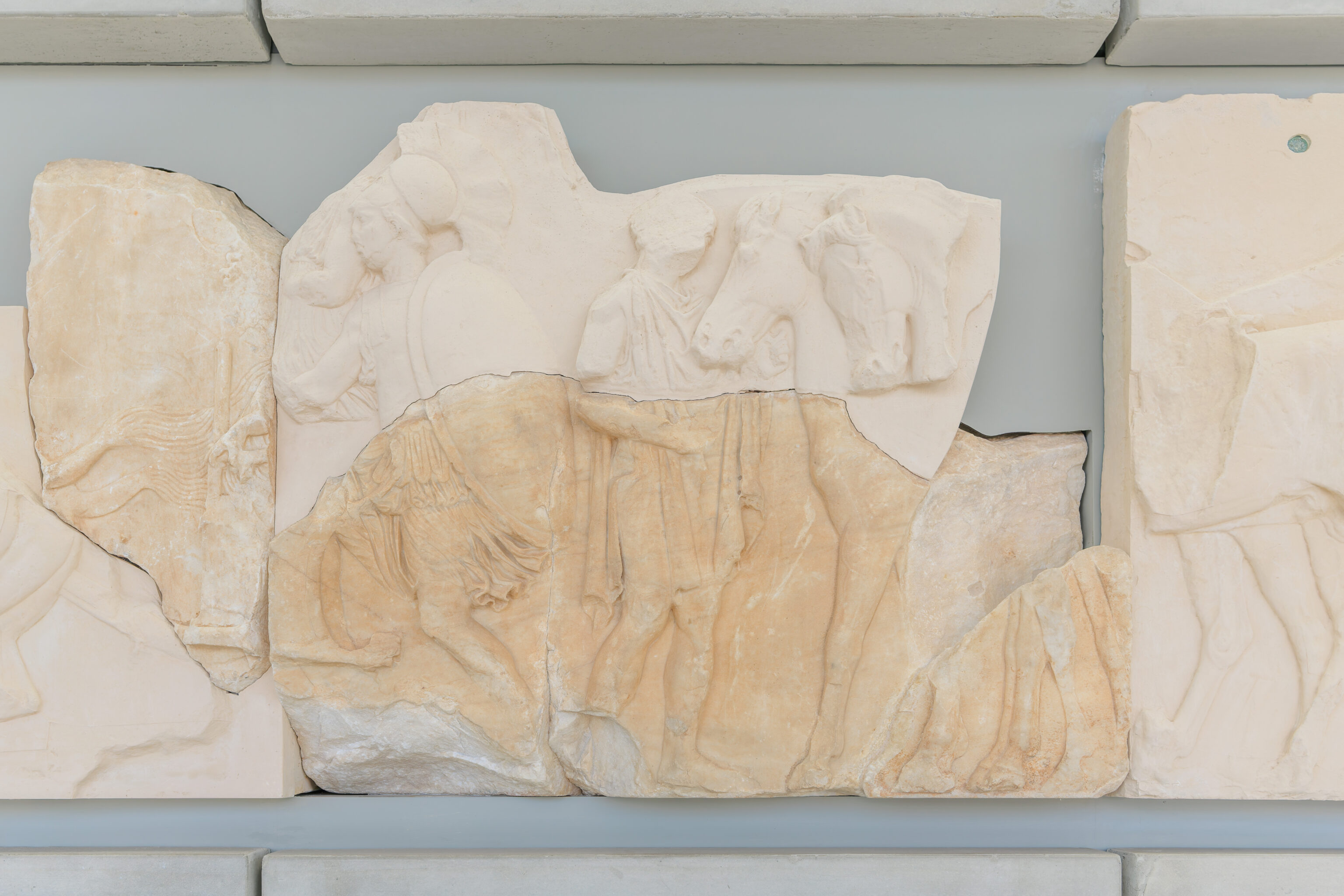

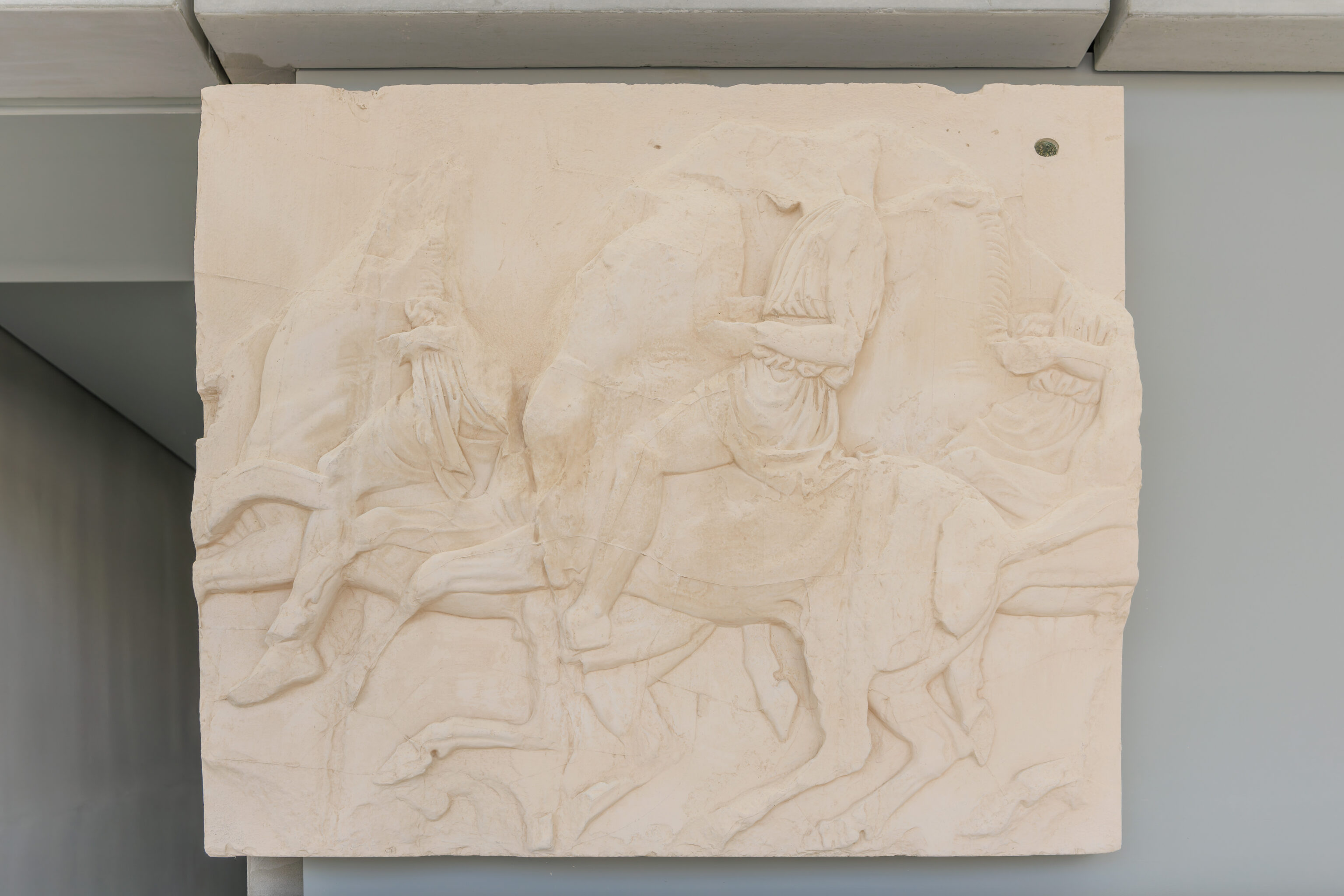

The Acropoli station has a replica of the frieze atop the Parthenon.

The sign on the left describes this frieze:

The west frieze of the Parthenon

A continuous frieze, carved in low relief, completed the decoration of the Parthenon and at the same time constituted a structural feature of the building. It was 160 metres in length and ran above the colonnade of the pronaos and the opisthodomos and the walls of the cella. The frieze blocks were laid in place on the building between 442 and 438 BC and probably carved in position. The theme of the frieze is thought to have been inspired by an actual event, the procession of the Panathenaia festival. The Great Panathenaia were celebrated every four years in honour of the goddess Athena and included various religious activities, as well as horse racing, music competitions etc. The culmination of the feast was the procession to the Acropolis and the offering of a new peplos (robe) to the votive statue of Athena Polias, on her birthday.

Two separate streams of figures started off from the southwest corner of the building and, moving towards the east side, met up above the entrance of the temple, where the peplos was delivered in the presence of the Olympian gods. The west frieze, copies of which are exhibited here, depicts men and youths with their horses preparing for the procession. Some are fitting the bridles on their horses or adjusting their own garments, others are starting to mount and ride towards the northern side, where the procession has already started. Some are hoplites, as is indicated by their breastplate, helmet or sword. On the left hand side of the frieze a marshal (an official responsible for the flow of the procession) motions with his left arm and turns towards the first two approaching horsemen. A youth prepares his horse with the help of his young servant, in the presence of an official. Subsequent blocks depict various scenes from the preparation of the procession, interposed with figures of one or two horsemen riding at a steady canter. The scene that decorates the middle block is exceptional: a mature rider trying to restrain his rearing horse. It is one of the most beautiful compositions of the frieze and is considered to be the work of Pheidias himself.

On the west frieze, from a total of 16 blocks, the sculptured surfaces of the first two from the left were cut out by Lord Elgin's workmen and, in the form of slabs, are exhibited now in the British Museum. In 1993, the remaining blocks were taken down from the monument and transferred to the Acropolis Museum for preservation, conservation and exhibition.

Although we knew where the Acropolis Museum was located, we didn’t know where its entrance was. After exiting the Metro station, we walked past the southwest entrance to the Acropolis, the same entrance we used on our visit a few days ago.

The entrance to the Acropolis Museum is just past the Acropolis entrance. This wide path leads to the museum building. There is a ton of marble here like everywhere else in Athens!

There were some ruins below the museum. We continued ahead to the entrance queues.

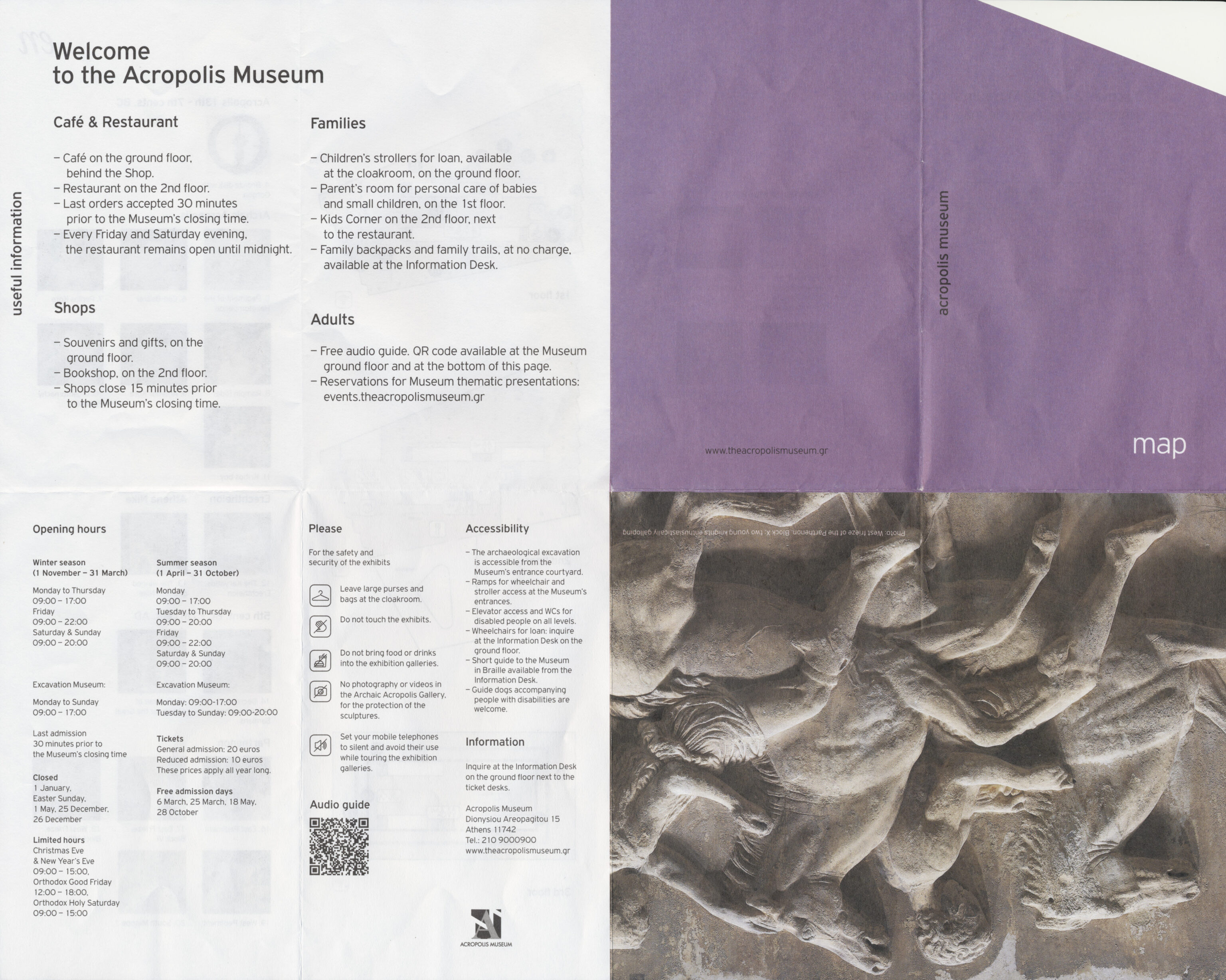

We picked up a paper map after entering. We’re glad that they still have these!

The first section of the museum has a glass floor which looks down upon the ruins below.

There were also some artifacts displayed below the glass floor.

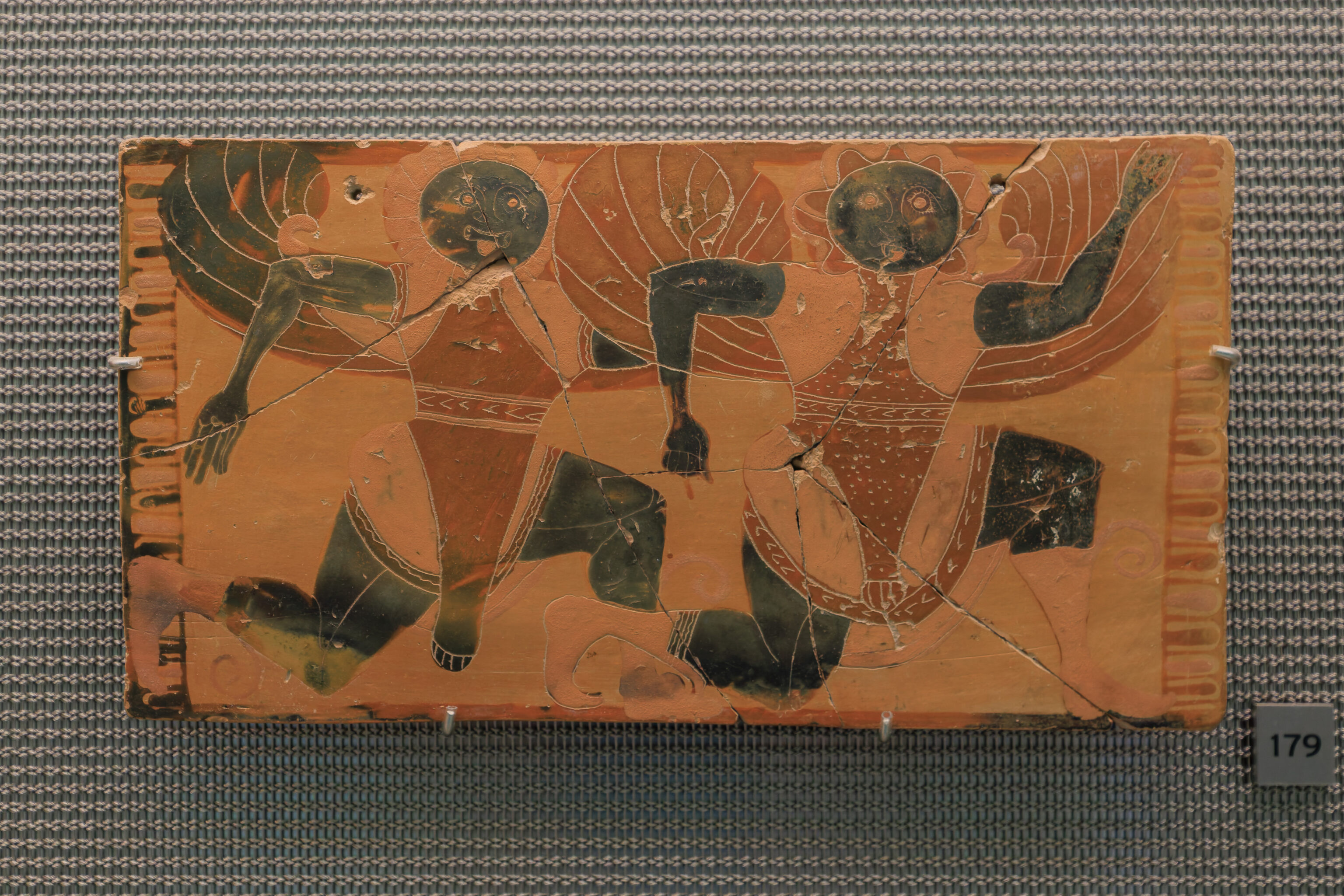

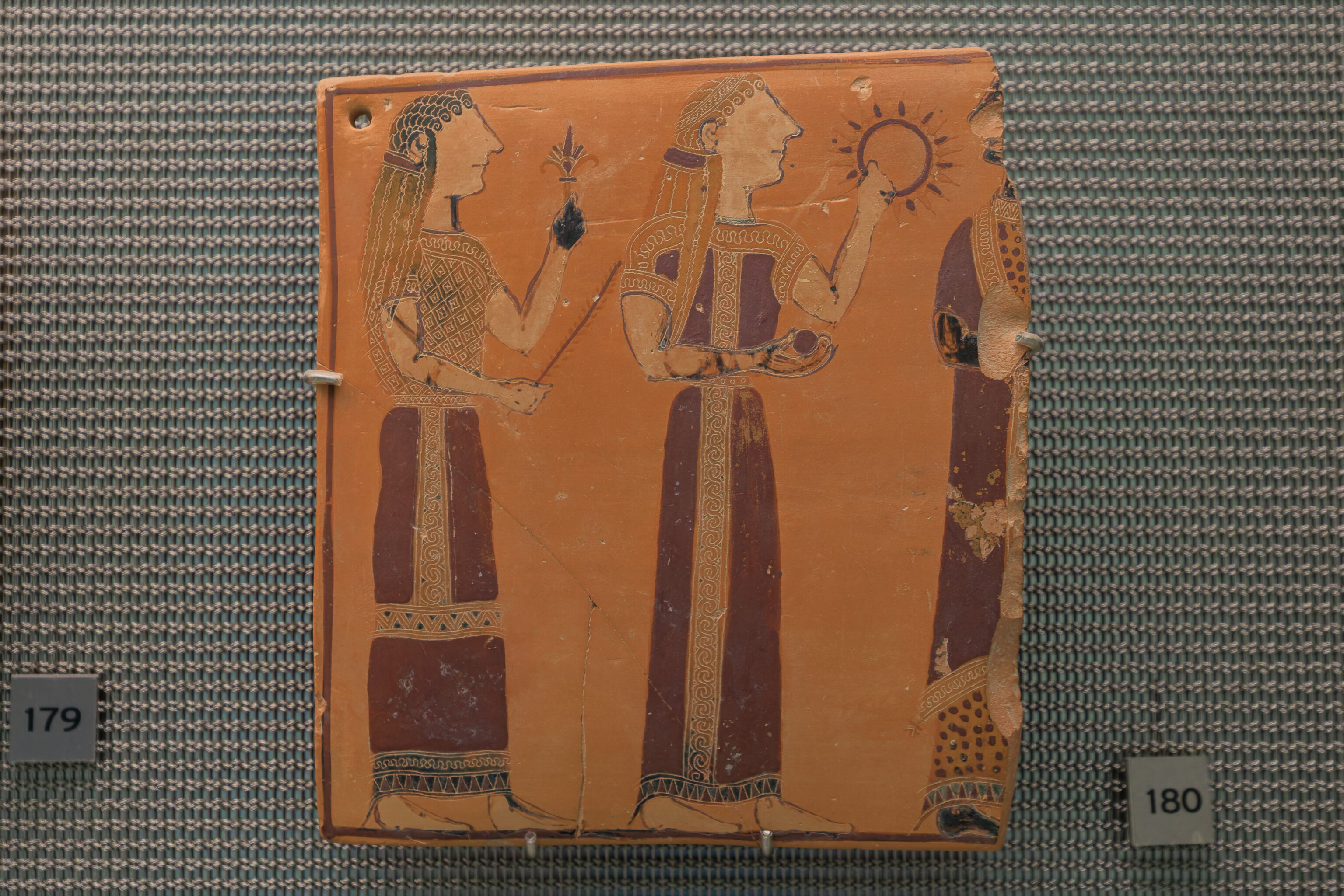

This first section held many pieces of pottery. The art on some of the pieces is incredible, particularly considering how old they are!

These two statues stood in the middle of the long room that makes up the museum’s ground floor. Or perhaps first floor is more accurate given that it is elevated above ground!

This one display held a many tiny pottery pieces!

We continued looking at all the various pottery pieces on display.

We continued on to find various sculpted items.

This stone container is interesting. It is described as a treasure box from the Sanctuary of Aphrodite Ourania. It is basically an ancient donation box and works like they do today. Donors put coins into the slot. There is a locking mechanism as well as a way to separate the two pieces to access the deposited money. This particular box is described as being for a couple’s wedding as an offering to the goddess Aphrodite to ensure happiness.

We continued on…

We enjoyed this small and rather lifelike depiction of an owl! It is from the Odeon of Perikles. It is described on a plaque:

Owl from the excavations in the Odeion of Perikles

A typical owl belonging to the species ot the Athene noctua which still inhabits the Acropolis area. It was used as a support for a seat in the odeion.

4th cent. BC.? Marble from Penteli (Acr. 3666)

This owl is referred to as the Owl of Athena.

After walking through most of the first floor, we looked back and could see one of the main features of this museum above, five of the six original Caryatids from the Erechtheion atop the Acropolis!

We headed upstairs where we saw these surviving elements of the western pediment from the Hekatompedos. This was an ancient building that was demolished to make way for the Older Parthenon which was destroyed by the Persians. The current Parthenon was built in its place. A small sign describes what we see here today:

Hekatompedos pediment

It consists of three groups that retain their vivid colors. In the central one, two lions devour a bull. In the left one, the hero Herakles fights against the Triton, the marine monster that was half a man and half a fish. On the right one, the so-called Three-bodied Daemon, a winged being with human bodies terminating in snake tails, holds in his hands the symbols of the three elements in nature: water, fire and air.

Around 570 BC. Poros

This was also part of the Hekatompedos, described as the end of a gutter.

…

This sphere is described as the Magic Sphere! Didn’t we see this in Lord of the Rings? And Harry Potter? The placard for this magical tool reads:

Magic sphere

On the sphere are presented the God Helios, a lion, a dragon and magical symbols. It was found buried near the Theater of Dionysos, which hosted duels and other similar contests when the sphere was created. It has been suggested that the sphere was used in magic rituals to achieve victory in these contests.

2nd-3rd cent. AD (EM 2260)

This is a marble throne of unknown exact origin. It was found at the Parthenon but is described as originating in an ancient Athenian public building. It was used in the Parthenon after it was converted to a Christian church.

A nearby sign describes the relationship between Athens and Rome during the Roman Empire before the sacking of Athens by the Herulians in the 3rd century AD:

Athens and Rome

The fate of Athens after its capture by Sulla in 86 BC now depended on its relations with Rome. The prestige of Athens' past, and Roman admiration for its intellectual and cultural achievements, led to the granting of an unusual degree of autonomy and a gradual revival of the city.

Thanks to the interest of many Roman emperors and the donations of numerous wealthy benefactors, Athens was able to rebuild. It acquired impressive public buildings and remained an important centre for the arts, letters and philosophy. At its schools studied statesmen, military commanders and important intellectuals such as Cicero, Horace and Ovid.

The Acropolis and its monuments became a source of inspiration for sculptors and architects and a promotional vehicle for the powerful personalities of the age. Roman architecture was heavily influenced, and wealthy Romans demonstrated their cultivation and good taste by collecting Greek statues, originals or reproductions. Attic sculpture workshops flourished, and their products, mostly copies and reworkings of older pieces, captured the markets in Rome and other major cities.

Athens benefited greatly from the idealization of her past. The Romans, as with the Hellenistic monarchs before them, endowed the city with important buildings, such as the Roman Forum, which was constructed with money from Julius Caesar and Augustus, and great works by the Emperor Hadrian (completion of the Temple of Olympian Zeus, the Library, the Pantheon and an aqueduct). Furthermore, the wealthy Athenian Herodes Atticus donated the odeum which bears his name (Herodeion) on the south slope of the Acropolis and funded the refurbishment of the Panathenaic Stadium in Pentelic marble.

The Acropolis, in contrast with the major works taking shape on its slopes and throughout the city, acquired no new buildings. This development, or lack of development, appears not to have been by chance but rather a conscious decision not to adulterate or spoil the place which embodied the classical ideal. The sole exception was a small circular temple dedicated by the Athenian Demos at the end of the 1st century BC to the Goddess Roma and to the first emperor Octavian Augustus.

The respect enjoyed by the Acropolis helped it retain most of its dedications, while other Greek cities and sanctuaries were plundered of their artistic treasures, which were then transported to Italy. By contrast, on the Acropolis a series of new dedications were added to the old: statues of gods, mainly Athena, portraits of emperors, bronze chariot groups featuring famous generals and other magistrates, portraits of philosophers, orators and priests as well as of regular citizens who had made donations to the city or distinguished themselves in athletic or other contests.

Athens' prosperity ended abruptly in 267 AD, after the invasion of barbarian tribes, the Herulians, who succeeded, before being driven off by the Athenians, in laying waste the greater part of the city. Many temples, public buildings, private homes and luxurious villas were reduced to ruins. The only monuments to survive were those on the Acropolis.

A nearby sign describes Athens after Alexander the Great and before its conquest by Rome:

Athens, the Acropolis and the successors of Alexander the Great

The conquests of Alexander the Great in the East brought radical changes to the ancient world. After his death in 323 BC, the lands of his immense empire were divided into smaller kingdoms, which were ruled by the dynasties of his successors. The city-state, which until then had been the primary political and administrative structure of ancient Greece, for all practical purposes now ceased to exist, and the Hellenistic kingdoms formed the new political, economic and cultural centres of the Greek world.

After the death of Alexander, Athens found itself still under Macedonian rule but was caught up in a series of clashes between the two states. In 322 BC, the general Antipater captured the city and forced it to accept a pro-Macedonian oligarchic regime, while in 317 BC, his son Cassander named the Athenian orator and philosopher Demetrios of Phaleron as the city's sovereign magistrate. This regime was overthrown in 307/6 BC by Demetrios Poliorcetes ("The Besieger"), and the Athenian state, out of gratitude, bestowed on him and his father Antigonos extraordinary honours.

In the years that followed, Athens often had to fight for its independence and for the restoration of its system of democracy. Even during those times in which it was successful, however, the city's autonomy was nominal, limited by outside forces and events, and supported by the benefactions of wealthy individuals.

Nevertheless, Athens was able to survive thanks to the brilliance of its past. The city continued to be the educational and cultural centre of mainland Greece, and students from all over the world competed to study under the great teachers at Plato's Academy, the Lyceum, the stoa of Zeno and the gardens of Epicouros.

From the classical 5th century, Athens' legacy of art and education was all that remained. Nevertheless, thanks to the lingering glory of this heritage, many rulers of the Hellenistic kingdoms endowed the city with grandiose buildings and erected magnificent sculptures on the Acropolis, following the example of Alexander the Great, who sent shields from the Battle of the Granikos River to hang on the epistyle of the Parthenon. From these dedications only a few have been preserved: a portrait of Alexander as a youth (Acr. 1331) which was made before he ascended to the Macedonian throne, and a few statue bases with inscriptions and scenes carved in relief.

From the 2nd century BC, Athens fell into the sphere of influence of a new world power, Rome. For her support, Athens was given control of the island of Delos (166 BC) and the enormous profits from the slave trade there. By and large, it was the upper classes of Athenian society which reaped the benefits of these profits and so became the most loyal supporters of Rome, gradually rendering democracy passive and impotent. Nevertheless, in the beginning of the 1st century BC, Athens switched camps and sided with Mithridates, the King of Pontus, in his fight against Rome. The consequences of this action were catastrophic: in 86 BC, the Roman general Sulla captured Athens after a siege of many months, put to death a large part of the population and leveled many sections of the city. This was the final and definitive end of Athenian democracy.

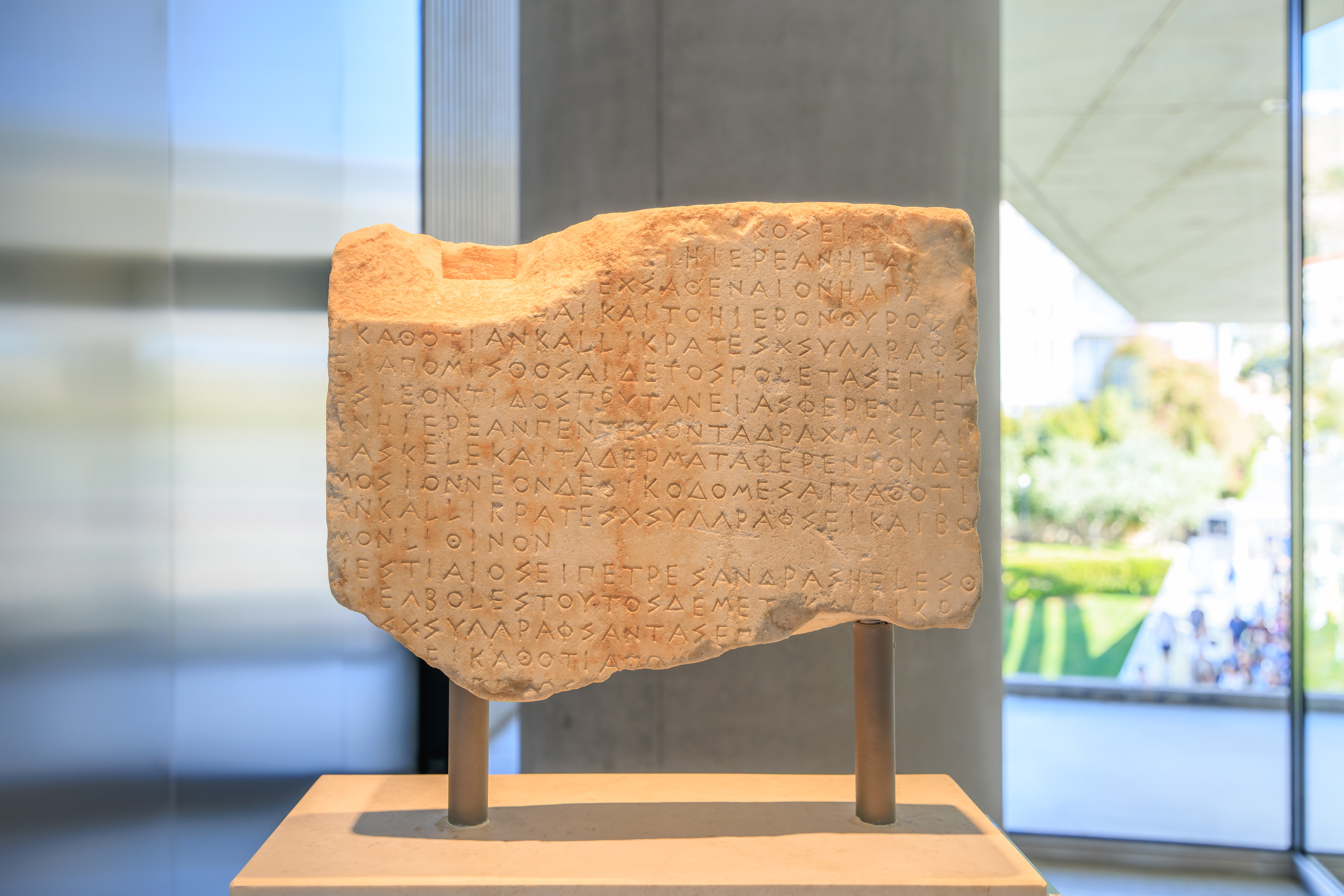

Another sign describes Athenian foreign policy during its democratic era:

The Acropolis and Athenian foreign policy

In democratic Athens, its citizens actually were the state. A gathering of a representative number of citizens comprised the ekklesia tou demou (Assembly of the People), which voted on the laws and published the decrees and resolutions which had been prepared for deliberation by the boule (Council). These resolutions defined, ratified or cancelled all activities of the state.

Every important decision of the Council and Assembly was made public and was binding on all Athenians, citizen and non-citizen alike. The texts of the decrees, which were first written on papyrus or wooden tablets, were then copied onto stone steles and placed where they could be guaranteed the widest possible public exposure: on the Acropolis, the city's center of worship, and in the Agora, the seat of its administrative bodies and offices.

During excavations on the Acropolis in the 19th century, many decrees were uncovered which involved the regulation of both domestic and foreign affairs. In the first category belonged decrees dealing mainly with the annual reports of the city's overseers, officers entrusted with the oversight of the budget for public projects or with checking the management of the sanctuaries' funds and economic affairs. In the second category are those decrees which regulated the treaties and alliances between Athens and other city-states or which granted certain privileges to her allies. The content of these decrees reflects the foreign policy followed by Athens in the 5th and 4th century BC.

The transformation, during the 5th century BC, of the first Athenian Alliance into an Athenian Hegemony led to rather blatant interference by Athens in the internal affairs of her allies. In order to consolidate her domination, Athens installed pro-Athenian democratic regimes in a number of other cities and did not hesitate to use force to bring back into the Alliance any members who tried to withdraw. During the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) between Athens and Sparta, Athens, acting with great diplomacy, granted significant privileges to cities of military importance - even though she then went on to increase the levies and contributions from Alliance members in order to pay for the war. The ruinously expensive campaign in Sicily (415-413 BC) ended in complete and utter disaster for Athens. Finally, the end of the war came with Athens' defeat at Aegospotami (405 BC) and her acceptance of the harsh terms of the Spartans (dismantling the city's defensive walls, surrender of all occupied territories, and return of political exiles).

In the early years of the 4th century BC, in order to confront Sparta's efforts to establish its own hegemony over Greece, Athens established the second Athenian Alliance (378/7 BC). Although the Alliance had been formed on the basis of full equality among its members, once again this principle was not upheld, and the most important members soon withdrew. In the war that followed, Athens did not succeed in winning them back into the Alliance, and the city, in its confrontation with the Macedonians (the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC) lost its independence.

All of the above events and developments: the wars, alliances and measures taken by Athens to secure her interests - are described in the decrees found on the Acropolis. The upper portion of the steles on which these decrees are inscribed were decorated with scenes connected with their content: the goddess Athena is often shown with the patron deity or eponymous hero of the allied city, or with the personifications of the cities, the Demos or Democracy.

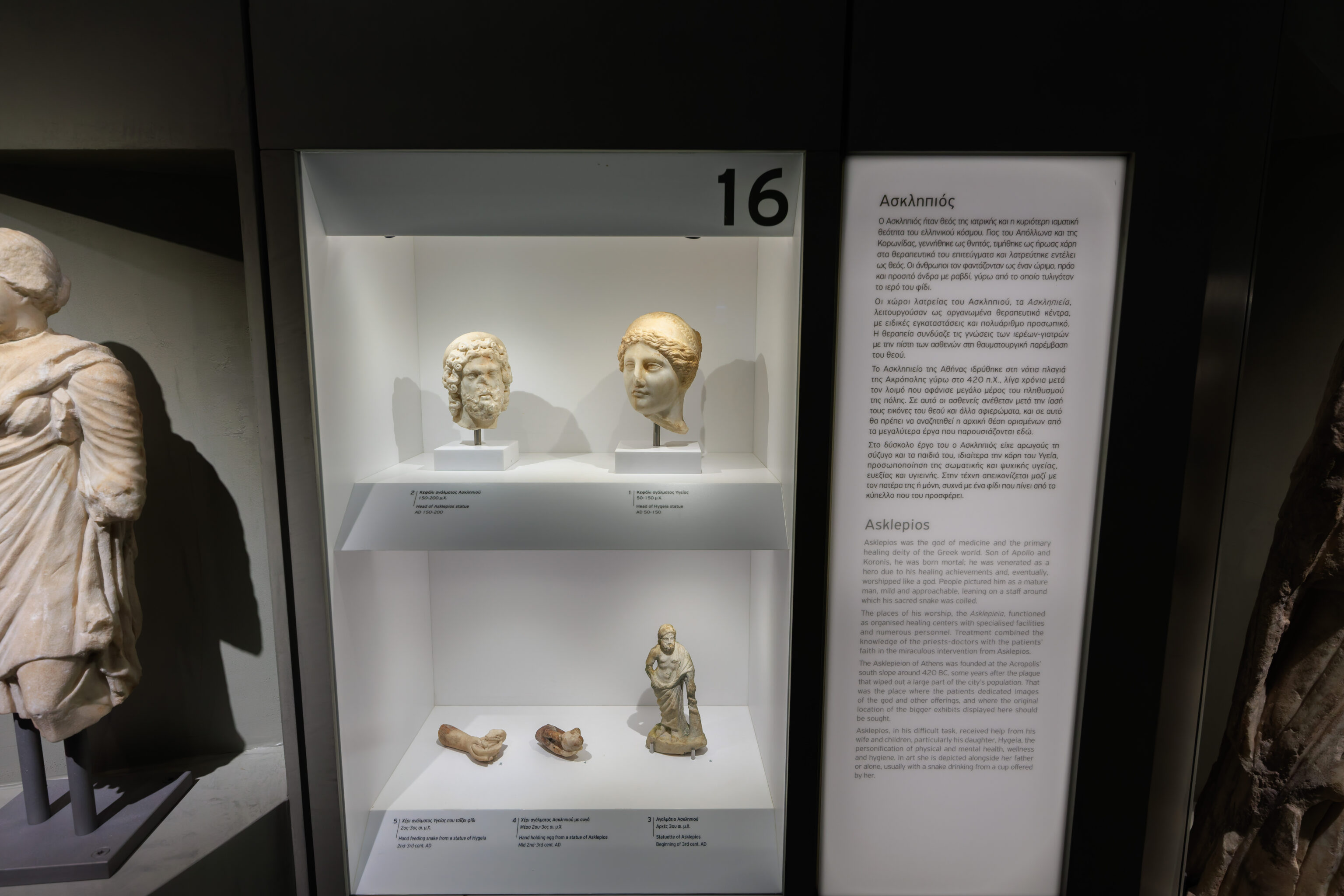

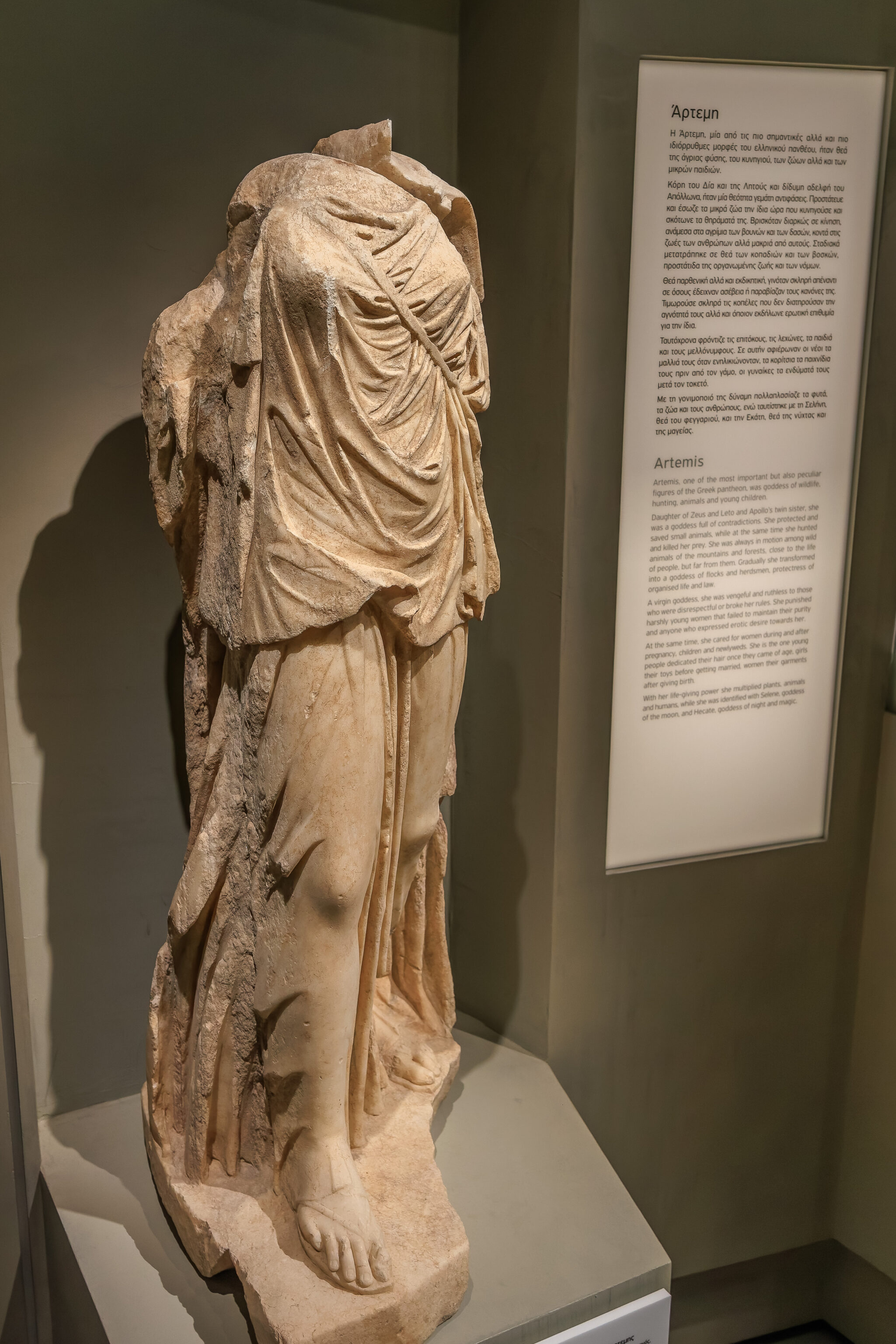

This is a bear, one of the animals associated with Artemis.

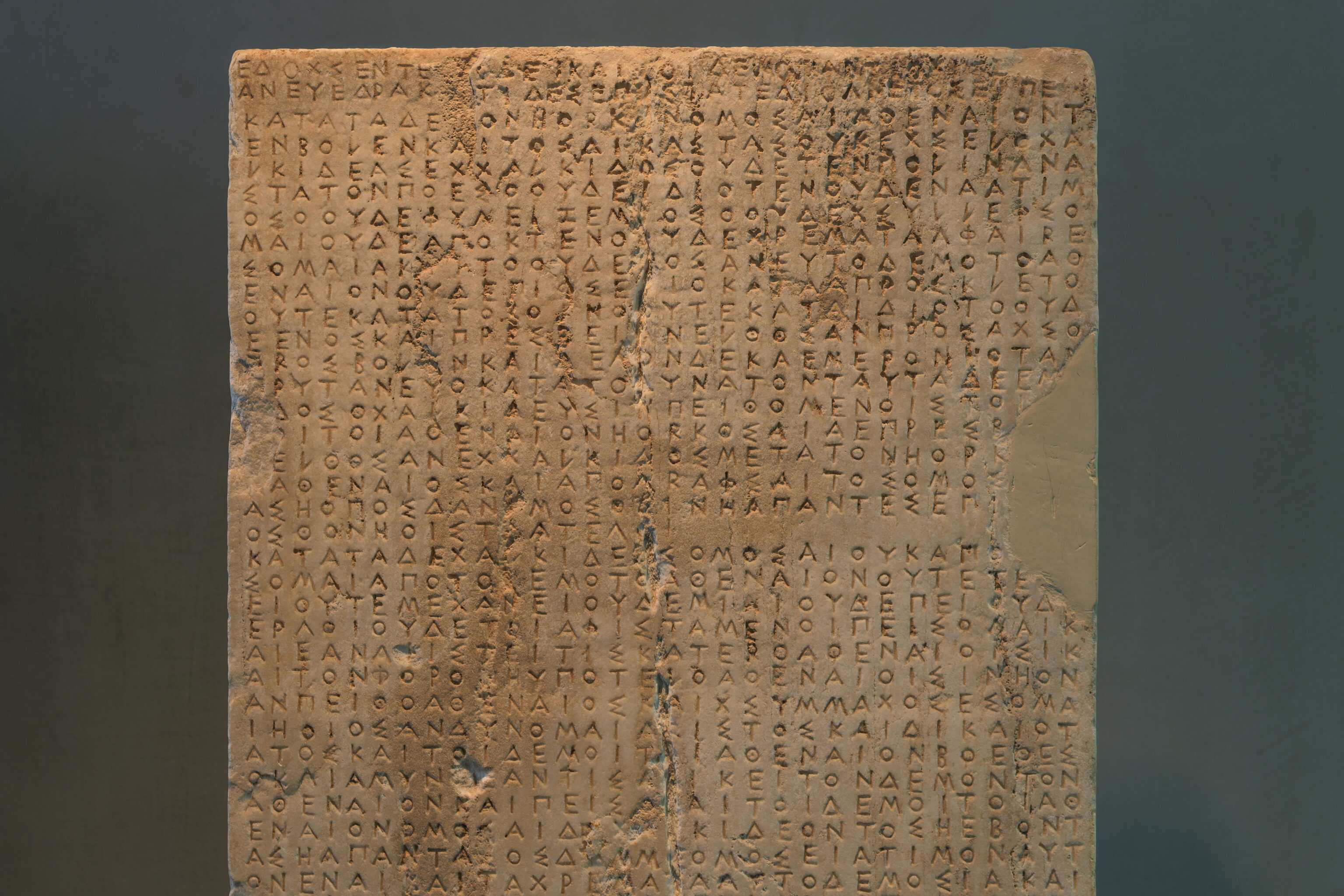

This stele from the Theatre of Dionysos contains decrees from the 5th century BC:

Decrees for Methone in Pieria

The Athenians bestowed economic, commercial and military privileges to their ally Methone, a city strategically located on the coast of the Thermaic Gulf. On the relief, the Goddess Athena extends her hand in a handshake with a figure accompanied by a hunting dog, perhaps the Goddess Artemis.

430/29, 426/5. 424/3 BC (EM 6596)

It seems almost like a literal wall of text that would be extremely hard to read!

…

We looked outside the window from this floor, the 2nd floor, and saw two huge queues to enter the museum! We’re glad it wasn’t nearly this busy when we first got here!

Somewhere, maybe around here, we noticed an owl sculpture on the outside of the museum. We noted that we should find it outside and take a photo. We forgot! The statue, described simply as Statue of an Owl, is actually mounted on a pole outside and dates back to the 5th century BC!

A nearby sign decsribes the various works of art that were present on the Acropolis around the 2nd century AD:

Votive offerings on the Acropolis during the classical period

When the traveler Pausanias visited Athens in the 2nd century AD, the Acropolis had the appearance of a vast open-air museum and was already a destination of choice for lovers of art and of Athens' glorious past.

The major building projects which had transformed the Acropolis during the 5th century BC, as well as the new dedications which had replaced those destroyed by the Persians in 480 BC, had completely altered the physiognomy of the Sacred Rock. The Acropolis of marble Korai (maidens) and horsemen dedicated by the wealthy families of archaic Athens gave way to an Acropolis filled with dedications from a democratic Athens and her politically enlightened citizens.

During the 4th and 5th centuries BC, it was the state, rather than private individuals or families, which placed the most marble or bronze dedications on the Acropolis. These depicted gods, heroes and mythical figures - as well as major personalities from public life, such as Pericles and his father Xanthippos. Of these dedications, few have been preserved. Their existence, however, is well known from descriptions by Pausanias and other ancient sources; from ancient copies of the original works; from the few bases which have survived, some bearing the signature of their creators, and from the depressions carved into the rock of the Acropolis where these bases were placed.

In the art of classical Athens, the mythological past was made to serve the democratic present. Through the allegory of myth, the city proclaimed its dominant position in the Hellenic world and inspired a sense of patriotism in its citizens. It was this vocabulary of myth which Alkamenes, the pupil and colleague of Pheidias, used in his statue of Prokne and her son Itys (Acr. 1358), one of the few 5th-century works to survive. The Athenian Prokne, daughter of King Pandion, killed her young son with her own hands in order to punish her husband Tireas, the king of distant Thrace, who had raped and dismembered her sister Philomela. Prokne, therefore, represented the ideal Athenian woman, placing her paternal family above her own married one, her Athenian identity above her personal pain.

Perhaps the most impressive of all the works described by Pausanias was the bronze statue of Athena Promachos (first in battle), which was created by Pheidias and dedicated to the goddess by the Demos (people) of Athens as an "aristeion" (recognition) for her contribution in the war against the Persians. The statue was placed between the Propylaia and the Erechtheion and reached a height of 9 meters. In the daytime, the tip of the spear carried by the armed goddess as well as the crest of her helmet shimmered and reflected the rays of the sun and could be seen from the sea by anyone approaching the coast of Piraeus. In the 5th century AD, the statue was removed to Constantinople and later destroyed. Today, the only traces which remain on the Acropolis are a few stones from the statue's base.

A fragment of a scene depicting a trireme found near the Erechtheion.

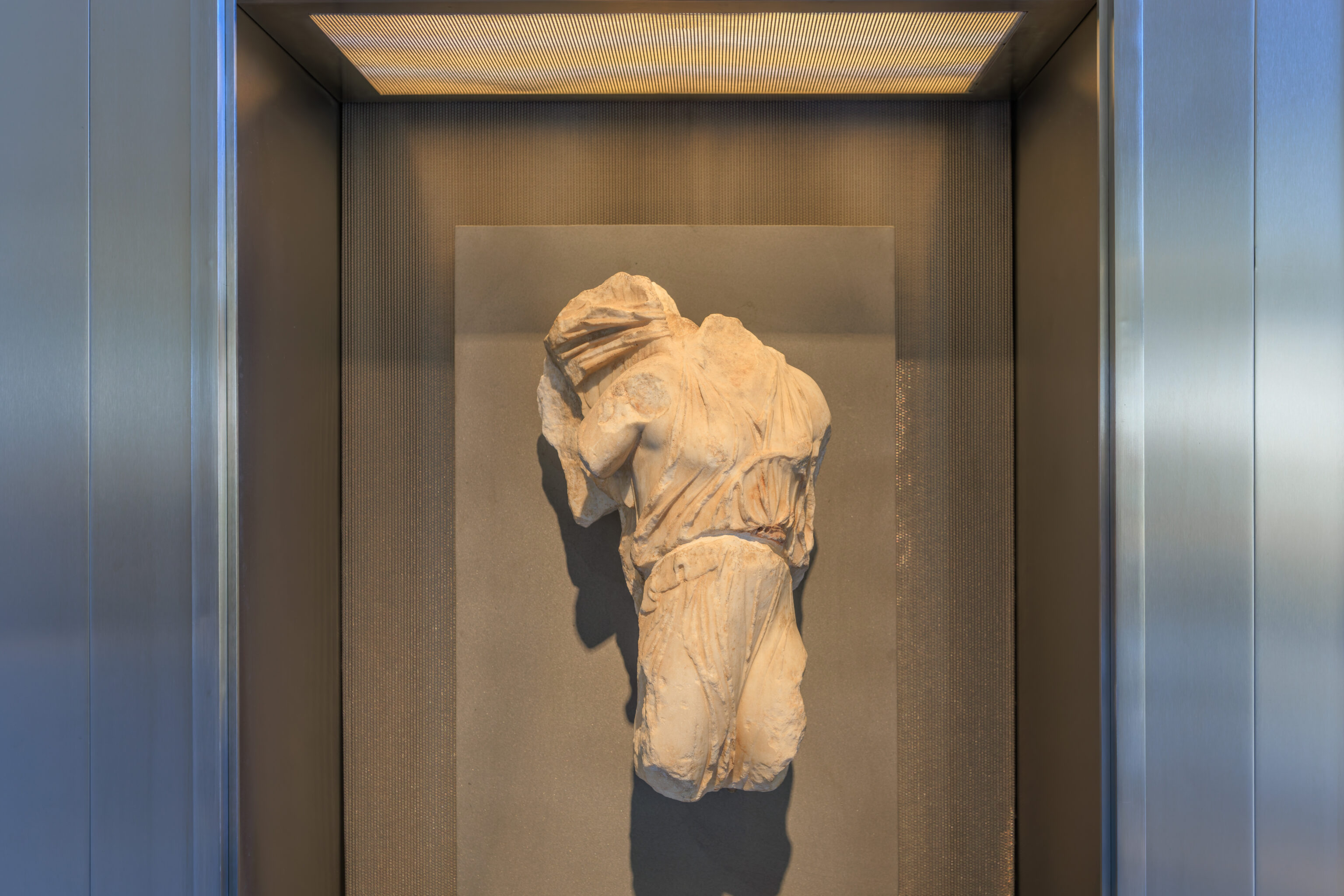

These are marble pieces from the Temple of Athena Nike atop the Acropolis.

A sign describes these marble pieces:

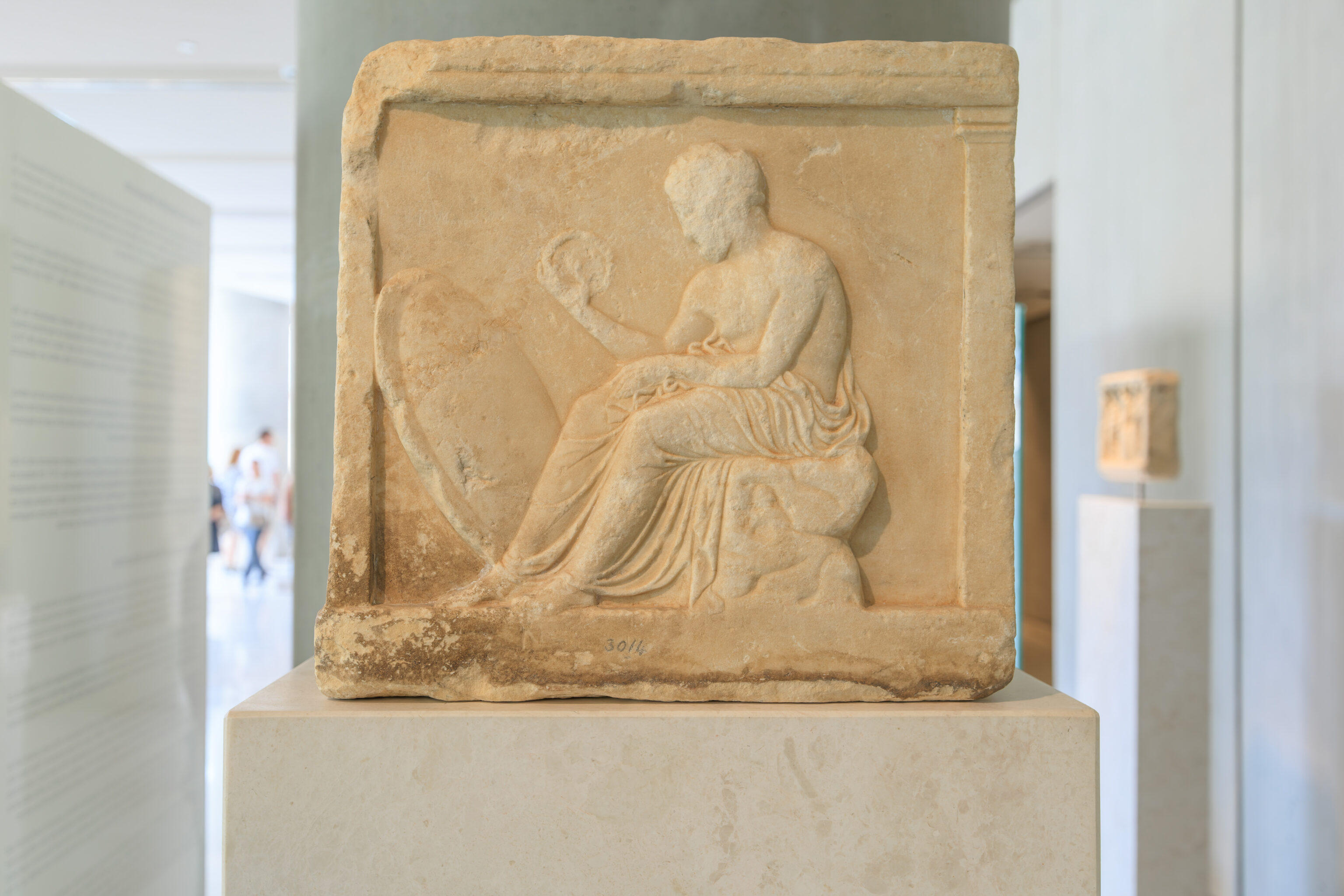

The Temple of Athena Nike. The balustrade

In order to protect visitors to the Temple of Athena Nike and prevent them from falling off the bastion tower where it was located, around 410 BC a marble balustrade (thorakio) was erected around three sides of the temple. This was constructed of marble slabs approximately 1 meter high, with scenes carved in relief on their exterior sides. Judging from holes drilled on the top of these plaques, it appears that a metal railing was added to increase the balustrade's height.

Most of the marble slabs have been lost, but from those which have been preserved it is clear that the scenes represent a celebration of Athena's victories over her enemies, both Persian and Greek.

The storyline is not continuous but is made up of separate, autonomous scenes which, with minor variations, are repeated on each of the balustrade's three sides: the Goddess Athena sits resting after her victorious battles and observes the winged Nikai leading bulls to sacrifice or carrying weapons and decorating victory trophies with Greek or Persian weapons and armor. Exceptional among these sculptures is the Nike adjusting her sandal (Acr. 973). These ethereal figures with their diaphanous clothing comprise the finest examples of the art of sculpture from the late 5th century BC.

This stele containing decrees is from the temple as well.

A nearby sign describes the Temple of Athena Nike:

The Temple of Athena Nike

Before the Propylaia could be completed, however, the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta forced a halt in Pericles' building plan for the Acropolis. At the first lull in the fighting, however, construction began on the small marble temple dedicated to Athena Nike, the goddess responsible for the city's military victories.

The temple was built between 426-421 BC on a bastion tower at the southwest edge of the Acropolis, following designs of the architect Kallikrates, as we have learned from an ancient inscription. It replaced other earlier temples whose remnants are preserved within the tower. The temple housed the wooden cult statue of the goddess (xoanon), which was adorned with gold and ivory. According to historical sources, the statue portrayed Athena holding a helmet in one hand and a pomegranate in the other, thus combining the militant and pacific aspects of her nature. In the 2nd century AD, the traveler Pausanias referred to the temple as belonging to the Wingless Nike and related that the Athenians had the statue made without wings so that Nike (Victory) would never leave their city.

The temple was Ionian in style and had a sculpted frieze showing different subjects on each side. The frieze on the temple's east side portrays the Olympian gods gathered around Zeus. On the other sides there are scenes of Greeks fighting Persians or Greeks fighting other Greeks. These are most likely historical, rather than mythical, encounters, about which various theories have been put forward. Most agree, however, that the south side depicts the Greeks defeat of the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, in which the Athenians played a leading role. The sculptural decoration of this temple, and of the entire sanctuary, celebrates their victories.

Only a few pieces of sculpture from the pediments have been preserved (display case 34). The west pediment probably showed the victory of the Olympian gods over the Giants, while the east pediment most likely presented the Athenians defeating the Amazons. The sculptures were carved by artists from the workshop of Agorakritos, a pupil and colleague of Pheidias. There was also an altar for sacrifices located to the east, at the entrance to the temple.

The temple survived for many centuries after the end of antiquity with practically no changes to its original form, although its function during this time is unknown to us. However, during the Turkish occupation (after 1458 AD), it was used as a gunpowder magazine. In 1686 AD, in order to repel the attacks of the Venetian forces under General Morosini, the Turks demolished the temple in order to use its building materials in the construction of a large tower in front of the Propylaia. From there Lord Elgin broke off four slabs of the frieze, which today can be found in the British Museum. The ruins of the temple were identified and reconstructed in 1835, shortly after the liberation of the Greek state from the Turks.

A nearby sign describes the Propylaia, the entrance to the Acropolis:

The Propylaia of the Acropolis

Already from the Mycenaean period, the summit of the Acropolis was protected by walls, which, with minor alterations and reinforcements, remained in place until 480 BC. After the Persian Wars, at the initiative of first Themistokles and then Kimon, new fortifications were built, while in Pericles' time the Propylaia complex was added, a monumental entrance which replaced the older gates of the sanctuary.

The Propylaia complex was designed and built between 437-432 BC by Mnesicles. The original plan, which was truly groundbreaking from both an architectural and artistic standpoint, was never completed in its entirety, probably due to a halt in construction on the eve of the Peloponnesian War.

The structure consists of a central entrance hall flanked by two wings. From the ceiling of one of them came the marble plaques (phatnomata) Acr. 280 and 639. Access through the Propylaia to the sanctuary was made through five different openings, the central entrance being the widest in order to accommodate the passage of the Panathenaic procession and its sacrificial animals. This central passage was lined by three pairs of Ionic columns, whose capitals were works of exceptional artistry - and parts of which are now on display in the Propylaia section of the Museum.

The north wing of the Propylaia contained a large room with antechamber, known today as the "Pinakothek" (Picture Gallery) from the description by the traveler Pausanias in the 2nd century AD in which he referred to paintings in the room portraying scenes from Athens' mythical and historical past. This room was probably furnished with couches and tables where visitors could rest and perhaps have something to eat.

The design for the south wing of the Propylaia originally seemed to have been the same as for the north wing. However, the presence of the preexisting temple of Athena Nike obliged the architect to change his plans. For this reason, only a "stoa" (roofed colonnade) was built in order to provide access to the small temple.

In the Propylaia were also displayed works by important artists, such as the "Hermes Propylaios" by the sculptor Alkamenes, of which the Hermaic stele (Acr. 2281) is thought to be a faithful copy.

After the middle of the 6th century AD, the Propylaia complex was converted into a Christian church, while during the middle part of the Byzantine period (9th - 12th century AD) the north wing was turned into the residence of the Bishop of Athens. During the time of Venetian rule (13th - 15th century AD), the Propylaia became an armed fortress and the headquarters of the Venetian, Catalonian and Florentine commanders, who transformed the north wing into a two-storey palace and erected a tall tower at the south.

During the time of the Turkish occupation (1458-1833), the Propylaia became the seat of the Turkish garrison commander, who used the central entranceway as a gunpowder magazine, which exploded in 1645 due to either lightning or a cannonball - inflicting on the monument its first truly catastrophic damage. After Greece's liberation from the Turks, the medieval and Turkish additions were demolished and excavations begun.

…

After reaching the far end of the second floor, we found the caryatids!

A sign describes these five original statues, which were building elements of the Erechtheion:

The Caryatids

The Erechtheion has two porches or porticos, on its north and south sides. The roof of the north porch is supported by six Ionic columns, while an opening in the floor of the building shows a mark which the Athenians claimed was made by Poseidon striking the rock with his trident.

The south porch is the better known of the two. In the place of columns, six sculpted Korai, the Caryatids, supported the roof. Although the name of their creator is unknown, it is thought that they are from the workshop of Alkamenes, a pupil of Pheidias.

Many interpretations have been offered for the Caryatids. The most convincing of these contends that they comprise the above-ground monument for the tomb of Kekrops, which was located directly beneath. These were the choephoroi (libation bearers), who were rendering tribute to the dead king, with phialai (shallow libation bowls) held in their hands, as we know from ancient reproductions.

The substitution of sculpted women for columns was not altogether rare in Greek architecture of the archaic period (7th - 5th century BC). The statues of the Erechtheion, in an inscription on the temple itself, were simply called Korai (maidens). The name "Caryatids" was given in later years because of their association with the young women of Karyai in Laconia, who used to perform a devotional dance in honor of the goddess Artemis.

Five statues of the Caryatids are located today in the Museum of the Acropolis, of which one was smashed by a Turkish cannonball, while the sixth is in the British Museum. In lieu of the original statues on the Erechtheion, cast reproductions have been put in their place.

They are quite impressive, even when damaged.

This is part of a statue of Athena.

This female lion eating a calf is likely from the east pediment of the Hekatompedos.

…

These pieces are all from the Temple of Athena Nike.

…

Photography was unfortunately not permitted in the section of the museum below. We don’t know why. Like the other parts of the museum that we’ve seen, it contains many sculptures, mostly statues. We were able to look down upon that area from the 3rd floor near the bathrooms.

The third floor has an outside area which offers views of the Acropolis to the north.

We could also see the Philopappos Monument atop the Philopappou Hill to the southwest of the musuem.

And, we could see the Lycabettus to the northeast.

It was still super busy below with super long queues!

The glassy modern building on the right is the eastern half of the museum.

The floor above, the highest floor in the museum, contains artifacts from the Parthenon. It is located in a large rectangular room surrounded by glass, which allows natural light in. Individual blocks from the Parthenon’s frieze are on display here. The Parthenon had 115 blocks in all with a total length of 160 meters. 50 meters of the original blocks are here while 80 meters are at the British Museum. There are a few blocks in other European locations, including one in the Louvre.

This section also displays blocks from the Parthenon’s metopes. The frieze was a continuous band of sculpted blocks between the Parthenon’s outer and inner columns. The metopes were on the outside of the temple above the columns.

Here in the museum, the frieze blocks are displayed lower on an inner wall while the metopes are displayed higher up on a band which runs around the room.

The windows on the north side have a fantastic view of the Acropolis. The higher elevation results in a better view compared to the outdoor area on the floor below.

Some of the blocks are completely missing while others on display here are reproductions.

These sculpted elements, presented on poles to reflect their original locations, are from the Parthenon’s west pediment.

This is a reconstruction of the arkoterion that stood atop the pediments of the Parthenon. This is basically the apex of the temple’s sloped roof with one on the east end and another on the west end.

A small sign describes this sculpture:

from nature to marble

The full reconstruction of one of the two akroteria from the Parthenon temple reveals its impressive size and illustrates the hybrid floral motif that it combines: a fan-shaped palm tree leaf which springs from acanthus leaves.

The four selected original fragments next to the reconstructed akroterion, exhibit wonderful details of the calyces, the stems, the jagged acanthus leaves and the blade palm tree leaves.

The floral akroteria on top of the Parthenon projecting on the blue Athenian sky, the continuous play of light and shadow and the slight angling of the leaves backwards - as if blown by the wind - completed the monument's façade and merged it with the natural environment.

These are four original pieces of the akroteria. They are depicted on the reconstruction in a warmer color.

This block is a metope, more specifically, South Metope 1. It was removed from the Parthenon in 2012.

This metope has its own small sign which provides a short description:

The metopes of the Parthenon were the first architectural sculptures to be fixed on the temple during its construction. The Centauromachy, or battle of the Centaurs, a favorite subject of the Athenians, metaphorically depicts the fierce struggle between civilization and barbarism.

South metope 1 was taken down from the Parthenon recently, after 25 centuries, to be preserved and exhibited at the Museum. The Centaur dominates the scene and gives the impression of being the victor. The blow, however, that he receives on the left thigh where the hole made by the spear of his Greek opponent is preserved is certainly serious. Like corner metope 32 on the north side, corner metope 1 on the south side is the work of a great artist.

…

These are elements of the east pediment. It’s interesting how the accommodated the horse’s lower jaw!

…

We’ve looped back to where we started from!

There are some additional items on display on this floor, which also contains a gift shop.

We bought an owl magnet.

We also bought two postcards featuring the owls.

We headed back out to see the ruins on the ground below the musuem.

There is a separate entrance on the west side of the museum building. Entry is included with admission to the museum.

A sign describes this ancient neighborhood just to the south of the Acropolis:

the ancient neighbourhood

An ancient Athenian neighbourhood stretches underneath the Acropolis Museum. Nesting on the gentle south slope of the rock, it houses life and human activities from the 4th millennium BC until the 12th cent. AD. Streets, residences, baths, workshops and tombs compose the complex image of archaeological remains. Amongst them those of late antiquity are the best preserved.

Today the visitor can only see part of what was brought to light by the excavations in the "Makrygiannis plot", as the area surrounding the Museum is named. Part of this excavation has been covered with a contemporary layer of earth to preserve it, while another was removed to make way for the underground levels of the Museum and the Metro Station ACROPOLIS.

Life here begins sometime between 3500 and 3000 BC. Until the 9th cent. BC houses, workshops and cemeteries coexist or succeed each other. Though sparse, the residential use of the site shapes from the middle of the 8th c. BC. Until the beginning of 5th cent. BC this area is located at the outskirts of the city, outside the fortification walls.

A major change takes place in the end of the 5th cent. BC when the area undergoes street planning acquires its urban character and is incorporated within the city walls. Until the beginning of the 1st cent. BC a dense street network develops, and houses with small interior courts, shops and workshops occupy the area. In 86 BC it is devastated by the troops of the Roman General Sulla and is abandoned for many years. A little later, industrial units are established on top of the ruins.

However, from the middle of the 2nd cent. AD the neighbourhood flourishes anew. The houses are now larger. Most of them acquire colonnaded courtyards, rooms with multicolor wall-paintings, and in some instances mosaic floors and private latrines. The most luxurious houses even feature private baths. This prosperity comes to a halt in AD 267 when the Herulians, a germanic tribe of the North, ravage the city of Athens and destroy the site.

The area is reorganized anew in the end of the 4th-beginning of the 5th cent. AD. All houses have colonnade courtyards but their character and dimensions differ. Next to smaller houses, probably belonging to middle-class citizens, stand larger and more luxurious residences, urban mansions of wealthy citizens.

Around the middle of the 5th cent. AD most residencies are repaired and continue to be used. At the same time a luxurious building with mosaic floors and a private bath (Building Z) is established at the place of two older mansions. It is the headquarters of a high ranking official or a local patron with ties to the Imperial court.

In the beginning of the next century, Building Z acquires a new wing, the Building E with innovative architectural features for the city of Athens. This building along others, restored or newly erected, indicates the continuity of urban life in a period when Athens is considered to suffer decline and urban shrinkage.

In the end of the 6th cent. AD some buildings are destroyed and others badly damaged. The lower level of Building E is converted to workshops that function, at least, until the beginning of the 8th cent. AD. They are later abandoned and for several years the area is abandoned. New houses and workshops appear in the 10th-12th cent. AD, which stay in use until the final abandonment of the site at the beginning of the 13th cent. AD.

In the beginning of the 19th cent. on top of the ruins of Building Z, the first military hospital of the city of Athens, known as "Weiler Building" is erected. Today this building houses the Acropolis Museum's administrative offices.

The ancient neighbourhood and the 4.500 year history which can be traced through its remains, is incorporated in a unique way in the Acropolis Museum architecture as yet another exhibit which converses with the masterpieces of the ancient Greek civilization presented in its galleries.

This seems to be the West Bath.

A sign provides more details:

West Bath

The private baths of the lavish mansions in this neighbourhood provide a luxury for the few. One of those baths, the West Bath, is established in the 2nd cent. AD by the wealthy owner of House E, located for the most part outside the borders of the excavation. It is destroyed in the 3rd cent. AD and the rooms of the next phase of the residence are constructed over it.

Visitors, upon their entry in the bath, leave their clothing in the changing-room (2). They cross the cold chamber (I) and reach the heated ones. First they enter the warm chamber (II) to give their body time to adjust to the temperature, and then to the hot one (III), for a steam-bath and a dip in the heated pool (IIIß). Afterwards, following the reverse route, they return to the warm chamber to get a massage and rubs with scented oils and finally to the cold chamber to cleanse their body from sweat and ointments and to obtain nice, firm skin by submerging in the cold water pool (la).

The bath's heating system forms between two floorings: an underground one, supporting a series of low poles and an elevated one, supported by those poles. The latter provides the ground where people walk on, wearing shoes with thick soles, to protect their feet from the heat and the water. The gap between the two floorings and a small gap between the double walls, permits the circulation of hot air, produced by the fire in the hearth (IIly) located under the heated pool.

The bath's size doesn't allow its simultaneous usage by people of both genders, and separate days or time were assigned to each one.

This area contains Building E. It sems to have been made up of many rooms with the circular foundation visible here at one of the corners.

A sign describes Building E:

Building E

In the beginning of the 6th cent. AD, Building E is founded over the ruins of houses r, H and ET. It constitutes a new wing added to, the slightly older, Building Z. The two buildings compose an impressive complex, covering a surface of over 5,000 m2, unique in Athens on this period. Its size and architectural features leave no doubt that it belongs to a prominent citizen of Athenian society, who has at his disposal wealth, power and authority.

Building E develops in floors with the upper one being the main residential quarters, while, the lower one, still surviving nowadays, housing auxiliary functions.

The core of the building is a large apsidal hall (50), where the host receives guests and treats them to dinner (triclinium). The hall connects with a chamber with three niches (51), perhaps a second triclinium for the owner's closer associates or a chapel for private religious practices.

Entrance to the lower level is achieved by six steps leading to an open-air antechamber (53) providing access to the surrounding areas. The northwest extremity is occupied by a large circular tower-hall (52), a relatively popular architectural element in mansions of late antiquity, not necessarily of defensive character.

This complex is destroyed in the end of the 6th cent. AD and soon after the lower level is used for workshops which remain is use at least until the 8th cent. AD. Their facilities include several constructions still visible in the area.

There were also public latrines here! They seem to be what now appears as various channels in the foreground.

A sign describes these ancient bathrooms:

Public Latrines

From the 2nd cent. AD most of the houses of the ancient neighbourhood have their own, private latrine. However, public latrines are erected, which operate consecutively in four different time periods, in an unoccupied area between three streets.

The two best preserved (3 and 4) resemble small houses and serve simultaneously seven or eight people. Although the seats with the characteristic openings were not found, the drainage trenches on the three sides however, are still preserved. These trenches receive the waste and with the help of running water are driven to the main sewer under the central street.

These latrines are a smaller-scale imitation of the large public latrines, known as "vespasians". The term "vespasians" derives from the name of the roman Emperor Vespasian (69-79 AD) who constructed many public latrines throughout the Empire. In the latrines on the excavation site, the arrangement of the drainage trenches on three sides is similar with that of the large public ones, but the latter accommodate more people.

Nowadays the simultaneous usage of such a private place seems strange and off-putting, but in antiquity it is the rule, as moral codes and the perception of timidity and privacy differ. The usage, however, of the public latrine by both genders remains a problem, which is probably solved with the establishment of separate hours per sex, as it was done in the small baths.

This area contains Houses H and Γ (Gamma), both from the 4th or 5th century AD. The square area with the decorated ground seems like it may be the courtyard for House Γ.

A sign describes these two houses:

Houses H and Γ are founded in the end of the 4th or the beginning of 5th cent. AD, a period of residential prosperity for the area and the whole of Athens. They constitute spacious, although not luxurious buildings, dwellings for the people of the middle class. Developed over the remains of older houses, they are in use until the beginning of the 6th cent. AD, when Building E is constructed over them causing major disruptions.

House H, on the left, is a small residence with six rooms. An entryway (1) leads from the street to the courtyard, the centre of family life (2). The courtyard, equipped with a well for the provision of fresh water, is surrounded on three sides by porticos. One of the rooms (3) might have served as the place where the owner would dine with his guests, the triclinium.

House Γ, situated on the right, is a larger residence with ten rooms. The entryway (1) leads from the street to the lowest level of the courtyard with the water-well (2). This courtyard is paved with marble slabs and multicolored plaques. A terracotta pipeline starts here and directs water to clean the latrine (5) whose waste is subsequently driven to the street's underground sewer. The courtyard is framed on three sides by porticos which lead to the other rooms. Large room 8 is probably the triclinium of the residence. Corner room 7, with its own well and separate entrance from the street, possibly functions as a store or workshop, which the house's owner either rents out, or personally manages it.

This was on the outer side of the path through the ruin area.

There seem to be some pipes and water channels here.

Thus is House ΣT (Epsilon Tau). It should in front of us, identified by the large courtyard with water well near its middle.

A sign describes this house:

House ΣT is constructed in the end of 4th and the beginning of 5th cent. AD over the remains of a previous residence. It is the largest house on the block where Houses H and Γ are also located. However it does not have the size and luxury of the mansions build at the same time in the northern, highest plateau of the area. It is inhabited until the beginning of the 6th cent. AD when Building E is erected over it disrupting its layout.

Access from the street is achieved through an entryway (1), which leads to the courtyard with the water well (2). A few fragments of the courtyard's terracotta floor tiles are preserved as well as part of the stylobate, which is the base where the columns supporting the roof of the porticos were erected.

The porticos surround all four sides of the courtyard, leading to the twelve rooms around it. These rooms provide us with no evidence of their function, with the exception of the large northern room (6) which should be identified with the triclinium, the place where the host would dine with his guests. The latrine (13), situated next to the entrance, is kept clean by water from the courtyard which is carried though a terracotta pipeline and subsequently diverted to the underground sewer of the street.

There is a small single room museum here at the furthest point along the more or less square route through the excavation site. This museum room had a queue to enter as it has a limited capacity. We queued for a few minutes before we could go in.

Like we saw up above in the main Acropolis Museum, there is a pottery collection.

There were also glass items…

As well as jewelry.

They even had dice!

We don’t quite recall what these little pieces are.

Keys are still recognizable!

This is a mortar and pestle.

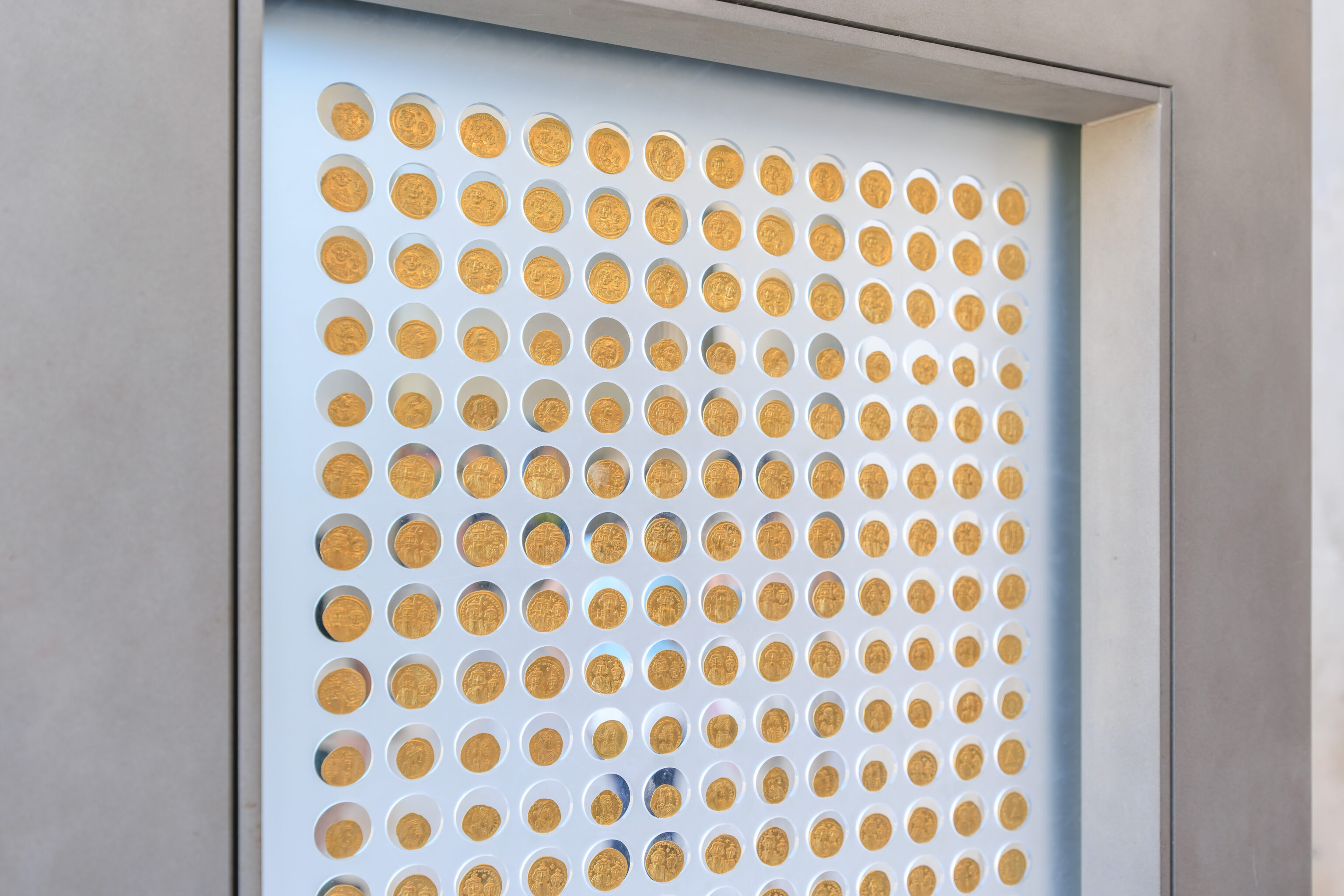

Some very old money!

There is quite a bit in this small museum.

This section of the excavation site was visible from the museum’s glass panel windows.

Text on the wall explains that many of the items here in this small museum were recovered from a cistern at one of the houses. When Athens was taken over by the Roman Empire in 86 AD, this are was pillaged and the residents possibly killed. Afterwards, when this area was repopulated, the leftover items were discarded into a cistern where they were recovered in modern times.

The cistern is described as being near House A at the western side of the excavation site. That may be somewhere near where we entered and unrelated to the area by this small museum.

The full text reads:

Due to a disaster

On the night of March 1, 86 BC, Athens was bound to live one of the greatest disasters in its history. After the month-long siege, the armies of the Roman general Sulla captured the city, killed part of its population, pillaged and levelled many areas. Among them the excavation site.

Years after, when new residents came to settle in the neighbourhood, they cleared the debris from the houses and discarded the destroyed household equipment into pits, water wells and cisterns.

One such cistern was the dumping place for the objects presented here. This is how an ancient catastrophe became the reason to reconstruct today the equipment of 1st century BC house and to obtain information about its form and the dietary and other habits of its inhabitants.

Cistern III, as it is conventionally called, was the water reservoir of House A, a house located in the western part of the excavation, which was also destroyed by the Roman army. Dozens of minor objects and thousands of fragments of clay pots were recovered from its interior and a significant part was able to be restored.

These were vessels for transporting, storing and measuring products, vessels for preparing. making and serving food, containers for oil and herbs, jugs and wine cups, beehives for honey production, lamps and loom weights, as well as vessels for perfume, cosmetics and jewellery. The original household equipment would have been certainly much larger if one considers vessels made of perishable materials that have not survived, or those made of metal that were recycled.

The large number and type of vessels, some of which were measuring utensils, lead to the suggestion that some kind of shop for selling liquid or solid products was operating out of the house's ground floor. This hypothesis is reinforced by the 19 lead tokens found inside the cistern (showcase 12, nos 63-81), which might have been used as coupons for purchasing the products.

A small section of a tiled floor mosaic.

This is described as a double-faced hermaic stele.

The sign for this stele has a drawing of what it may have looked like. We’ve seen this sort of thing before! On our first day in Athens, we saw a pair of similar steles at the Panathenaic Stadium!

In particular, we noticed the addition of genitalia on the stele which otherwise only has two busts at the top.

The English text on this sign reads:

Double-faced hermaic stele

1 st-2nd cent. AD (M 35)

One face depicts the god Hermes and the other Dionysos. In antiquity, hermaic stelae were considered sacred. They attributed to them protective and apotropaic properties and placed them at roadsides, crossroads and entrances to public and private spaces.

This one was last used in the middle of the 5th century AD, when it must have been placed outside the southern entrance to Building Z, where it was found.

…

This is a depiction of Empress Eudocia.

Its sign reads:

Portrait of Empress Eudocia

AD 421-430 (NMA 5257)

The statue would have stood in Building Z, implying a connection between its occupant and the imperial court.

Eudocia (AD 401-460), born in Athens under the name Athenais, was the daughter of the sophist Leontius, from whom she received a remarkable classical education. In AD 421, she married the Emperor Theodosius Il and converted to Christianity. As empress, she promoted literature and founded important public buildings in her native city.

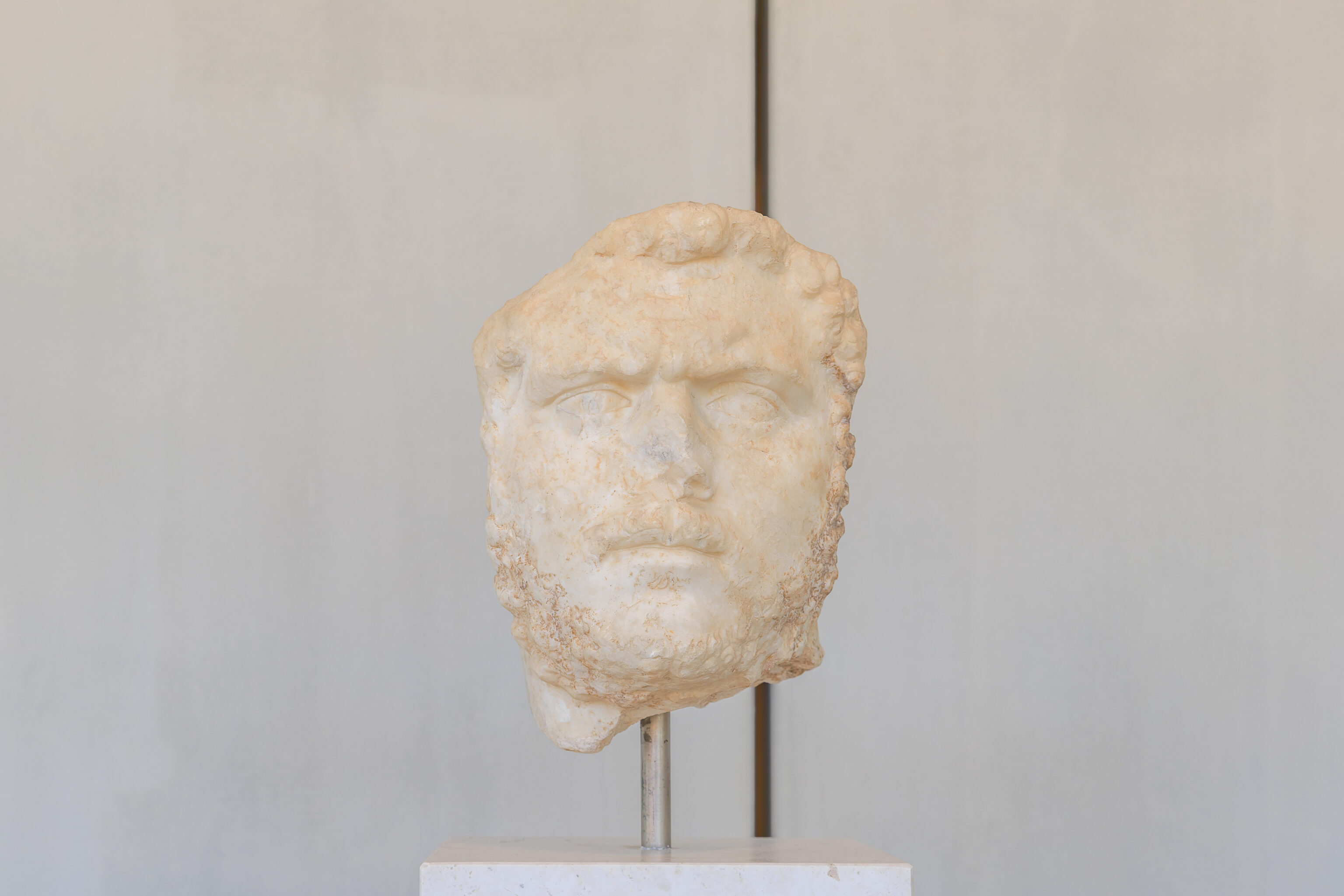

This bust depicts the philosopher Aristotle.

Its sign reads:

Bust of philosopher Aristotle

End of 1 st cent. AD (NMA 5053)

It is in the form of a herm that was probably placed at the entrance or the peristyle of the imposing Building Z.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) was born in Stagira, Chalkidiki. He was a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. In 335 BC, he founded his own philosophical school, the famous Lykeion or Peripatetic School, in Athens. His philosophical conquests formed the foundation for the development of science in the Western world.

This bust depicts the philosopher Plato.

Its sign reads:

Bust of philosopher Plato

1 st cent. AD (M 163)

It comes from a hermaic stele, which may have adorned the mansion of a cultivated inhabitant of the area.

Plato (427-347 BC), a leading figure of all time, was born in Athens. He was a pupil of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle. In 387 BC, he founded his own philosophical school, the famous Academy, in Athens. His work, in the form of dialogues, had an enormous influence on ancient and modern Western philosophy.

…

This marble panel depicts three gods – Baal, Iarhibol, and Aglibol.

Its sign explains:

Relief with the trinity of Palmyra

The trinity of gods from Palmyra, city in Syria, with identifying and allegorical symbols. At the centre is Baal, ruler of the sky and the world's destiny, on the left is larhibol, god of the sun and on the right Aglibol, god of the moon

Probably 4th cent. AD (NMA 1825)

These two figures depict Zeus Heliopolitanus and a mix of the Egyptian Osiris and Greek gods Dionysos and Aion.

Each has a sign:

Statue of Zeus Heliopolitanus

Zeus in the aspect he was worshipped in Heliolopis of Syria (Baalbek in Lebanon) as a young god of agricultural nature and fertility

End of 1st cent. AD (NMA 96)

Statue of Osiris-Dionysos Chronokrator

The Egyptian Osiris, god of vegitation, the Underworld

and resurrection assimilated with Dionysos and Aion.

the everlasting time who rules human life

End of 2nd cent. AD (NMA 282)

…

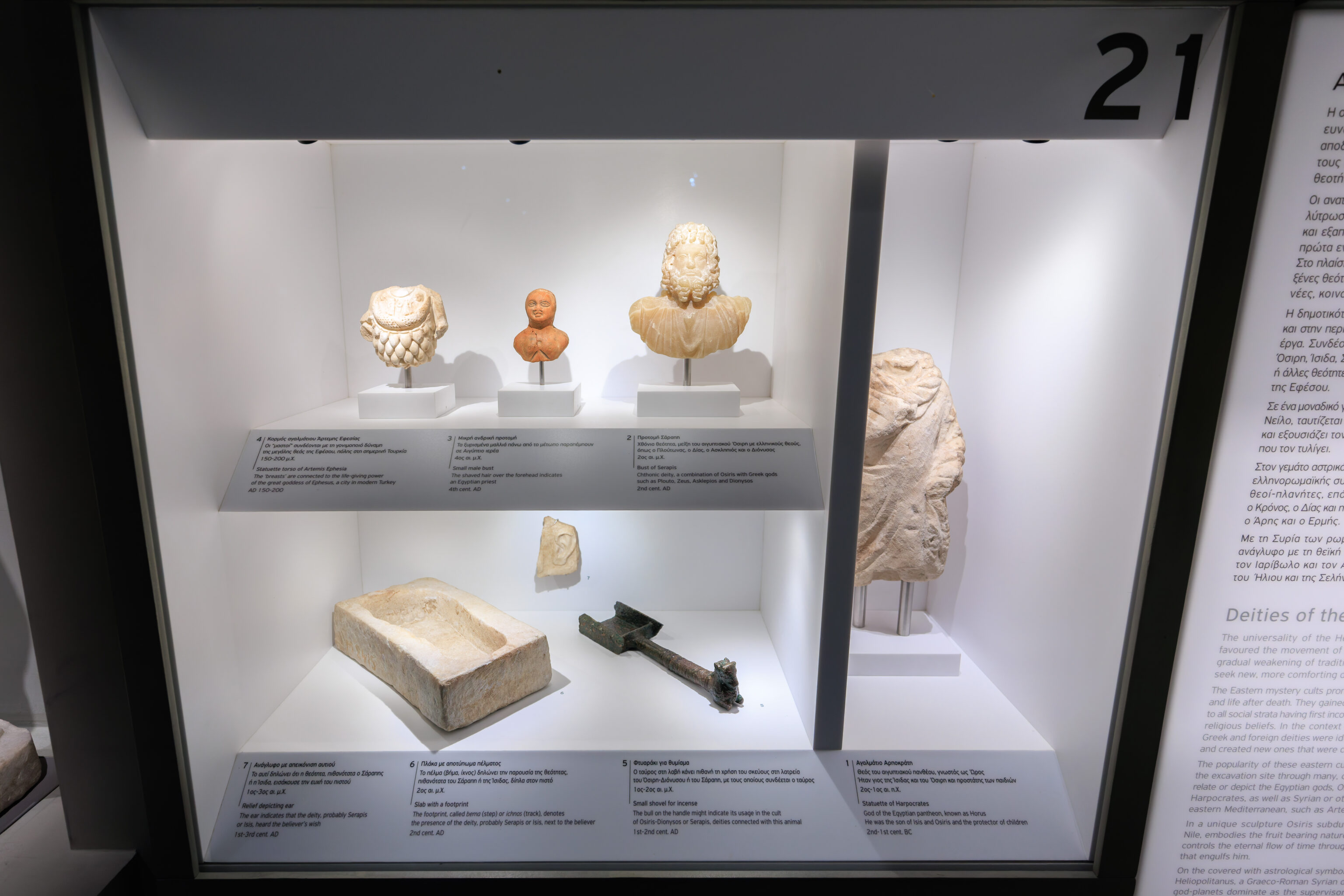

This piece depicting Artemis is notable because our last trip was to Rome where we saw something similar. Its sign reads:

Statuette torso of Artemis Ephesia

The 'breasts' are connected to the life-giving power

of the great goddess of Ephesus, a city in modern Turkey

AD 150-200

We continued on after exiting the museum. A few building parts were neatly arranged near the walkway.

We continued through the remainder of the route before exiting the same way that we entered.

We decided to continue on via a path to the south on the west side of the Acropolis Museum.

Lunch

It was almost 1:30pm by the time we exited. So, lunch time! We decided to eat at Piato El Greco (The Greek Plate), a restaurant one block away from the southwest corner of the Acropolis Museum.

Decorations in the interior of the small restaurant.

We spotted this cat outside from our table by the windows, which were open. This restaurant had the large window door panels which could be folded or moved out of the way.

We ordered the Grilled Pork Belly Chops…

And the Lamb Shish Kebab. Both were good!

This column from the 2nd century AD was across the street from the restaurant, which can be seen here in the background.

Odeon of Herodes Atticus

We decided to head to the Areopagus via the south side of the Acropolis, traveling on a route that we haven’t walked yet.

This was the view to the east, back towards the entrance to the Acropolis Museum which isn’t visible from this perspective. The Acropolis is to the left.

The Acropolis, as seen from the same spot.

We started walking to the west. This was two streets away.

We turned in the opposite direction to walk towards the Acropolis and the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, which was directly in front of us.

Some columns below the modern street level.

We arrived at the base of the odeon. So far, we’ve seen it from the other side while at the Acropolis and we’ve seen it from a distance. We haven’t yet seen it from this perspective.

It wasn’t possible to enter the odeon, though we could see through a doorway into a passageway into the odeon. The odeon is still in use today so we assume one or more of these are used for entering and exiting.

The view to the west showing the rear of the ruins of the stage building.

A nearby sign describes the Odeon of Herodes Atticus:

The Odeion of Herodes Atticus (160-169 A.D.) was donated to the city of Athens by the famous orator, sophist and great benefactor of the city, Herodes Atticus, in memory of his wife Rhegilla. It was used for musical events and philosophical lectures.

Its semicircular cavea has a diameter of 76m and contained 39 rows of marble seats that could host up to 6,000 spectators. The marble paved orchestra is also semicircular and has a diameter of 19m, while the huge rectangular proskenion had a wooden floor 1.5m above the orchestra. It is 35m long and its façade projects 8m in front of the south wall of the concert hall. Further to the south, was the stage with a luxurious mosaic floor. Unfortunately, the external walls of the stage are the ones least preserved. Towards the proskenion, pilasters and columns framed the three doors of the stage and the doors of the side walls: The monument had a roof of cedar wood, without intermediate braces. This was a great achievement, commemorated with admiration by ancient writers like Pausanias and Philostratos. To the east, the Odeion was so perfectly connected to the Stoa of Eumenes, that one would assume that the Stoa was built to serve the Odeion, while, in reality the Stoa had been built three centuries earlier, for the spectators of the theatre of Dionysos.

The Odeion was burned down by the Herulians in 267 A.D. Later it was incorporated in the Late Roman fortification wall of the slopes of the Acropolis, which remained in use with various modifications until 1877. In this way the monument survived demolition and stone pillaging so that its southern wall still stands to a height of almost 29m.

Archaeological excavations (1847 - 1858) conducted by Kyriakos Pittakis freed the Odeion of Herodes Atticus of medieval deposits 10m high and shed light to its history. The reuse of the Odeion for musical events and theatrical performances started in the 1930's and became regular after 1957. For this purpose the marble seats of the cavea and the staircases were reconstructed under the direction of Anastasios Orlandos (1960-1964).

Some of the doorways had views of the seating area opposite of us. We could see many Acropolis visitors looking down from above. We were there too when we visited!

This passageway held a statue at the far end.

The view looking to the east from the west end of the odeon.

We noticed one piece of probably new marble up above in an alcove, or rather, just a gap in the outer wall of the structure. There are words carved into it but we can’t read it from this distance.

We continued on, following a path that led southwest onto the wide pedestrian street that we were on before.

Aeropagus

We continued on, reaching the a junction that we’ve been to before. We continued on to the northwest.

We could make out some ruins on our right. The Pnyx, which we visited the day before yesterday, is behind us from this perspective.

We spotted a resting cat.

We came across a tile mosaic floor, also on the right.

A sign describes this area:

STENOPOS KOLLYTOS AREA

The area between the hills of the Areopagus and the Pnyx was known as the "Dörpfeld Excavations" area, after the archaeologist who excavated it in the years 1892-1898. It belonged to the central part of the ancient municipality of Kollytos. "Stenopos Kollytos", a narrow carriageway 4 m wide, passed through the houses, workshops and shrines of the municipality. This main street was crossed by other thoroughfares that led to the Acropolis, the Areopagus and the Pnyx.

On the west side of the street was located a building of the 4th cent. B.C. called the Leschi (club), which was built on a pre-existent temple of the 6th cent. B.C., dedicated to a deity whose name has not been preserved. The Leschi served as a gathering-place for the homeless.

On the same side of the street to the south are remains of large houses dated to the period between the 4th cent. B.C. and the 4th cent. A.D. For two of them, the "House of Periandros" and the "House of Aristodemos" their owners' names have come to us, from mortgage inscriptions incised on their external walls. Another private residence, known as "the House of the Roman Mosaic", had an elaborate mosaic floor of the 2nd cent. A.D., with a pair of parrots drinking water out of a vase.

Two important shrines of the 6th cent. B.C. with numerous votive offerings and inscriptions, were found on the east side of Stenopos Kollytos. The shrine at the north end was identified with the Dionysio en Limnais, or alternatively, the Shrine of Herakles Alexikakos. It consisted of a triangular enclosure, within which was a small temple. It had a roofed altar and a winepress, added in the 4th cent. B.C. The Baccheion, an oblong, three-aisled hall, was constructed in the eastern part of the shrine in the 2nd cent. A.D. This was the meeting place for a religious and social group, the Thiasos ton lobacchon, followers of the cult of Dionysus. To the south lies the Amyneion, an open-air sacred enclosure, dedicated first to the Attic hero and healer Amynos and from 420 B.C. to both Amynos and Asclepius.

Another residence, known as the "House of the Greek Mosaics" (4th cent. B.C.-4th cent. A.D.), was located between the two shrines. It had a central court surrounded by many rooms, some bearing pebble mosaic floors.

This door is labelled Fountain of Pnyx.

A sign describes what we see here:

During the rulership of the tyrant Peisistratos (6th cent. B.C.) the growth of the city's population necessitated the construction of a well organised system of fresh water to supply the city's needs. An extremely complex water-providing net was opened, subterrain in a great extend, divided into several branches, covering a distance more than 9.500 m. The fresh water was led from Hymettus into the town through sealed clay pipes, laid in underground tunnels of stable inclination, necassary for a continuous flow. A certain branch of this network has been traced at the east side of the Pnyx hill, and supplied water for more than eight centuries to a system of rock-cut and build cisterns.

Due to the poor state of knowledge of ancient Athenian topography during the beginning of the 20th century, German excavator W. Doerpfeld described these installations as the "Enneakrounos" fountain of the tyrants and the "Kallirroe" spring. Already by that time this identification was seriously questioned. Today the most prevalent theory sets "Kallirroe" in the area of the llissos river, SE of the Olympeion while "Enneakrounos" is according to the description of Pausanias the archaic fountain that has been discovered in the SE side of the Agora.

Nonetheless, the installation of the chamber-like, rock-cut fountain in the east slope of the Pnyx hill, is still conventionally named "Kallirroe". It consists of a rectangular chamber, chiselled into the bedrock with a shallow well across the entrance, where the water was collected. A second subterrain chamber on a lower level, is connected to the former with a stepped corridor. By the time of the emperor Hadrian (2nd cent. A.D.) the floor of the first chamber was decorated with an elaborate mosaic.

During the Second World War the "Kallirroe" was used as a shelter to protect antiquities and the entrance was sealed with concrete.

Some more ruins can be seen here along with a small Greek flag. The Acropolis can be seen in the background above the trees.

These caves, at the base of the Pnyx on the left side of the path, are described as possibly being used as a sanctuary for the worship of Pan.

A sign explains:

Archaeological research conducted during the works of the Unification of the Archaeological Sites of Athens close to the intersection of two ancient roads, revealed a rock-cut, underground chamber, accessible through a door-shaped opening. Excavation inside the chamber uncovered in the north wall a relief, chiselled directly on the bedrock, presenting Pan, a naked Nymph and a dog. The presence of this relief led to the identification of this monument as an unknown, not reported by any ancient writer, sanctuary of Pan.

The cult of Pan in caves is well documented in the countryside of Attica at 5th century B.C. (caves of Vari, mount Parnes, mount Penteli, Marathon) as well as inside the ancient city (NW slope of Acropolis).

Excavation on the exterior installations of the chamber also revealed wall-paintings and a mosaic, both related to architectural reformations of late antiquity. In close distance above the chamber, the coursed roadway of the "East Road", chiselled on the bedrock, is still visible as well as important remains of two rock-cut houses or the classical period, with an intact system of subterrain cisterns.

Normally, the Areopagus is accessed from an entrance near the western entrance to the Acropolis site. However, the Areopagus entrance is temporarily closed for construction. Instead, the Areopagus can be accessed from the west. The western entrance is through a simple open gate near where we descended from the Pnyx when we visited. This entrance is near the beginning of the community to the north of the Pnyx. South of this entrance, there is park land on both sides.

There is no real official route here. Basically, find a path up that seems acceptable and keep going up!

Soon, we ascended enough that we could see above the trees to the north. This area is just above the south side of the Ancient Agora, which we recently visited. The Temple of Hephaestus, within the Ancient Agora, is visible from here.

We continued on a bit further. Looking to the west, we could see the top of the Pnyx. It isn’t too much higher than we are.

We walked a little bit further. Looking to the northeast, we could see the Lycabettus in the distance.

This location, on the northern edge of the Areopagus, gave us a nice view of the Ancient Agora below. We could see all the major structures that remain below.

We walked a bit further, reaching the rocky peak of the Areopagus. We didn’t try walking any further as after my torn ACL, I tend to avoid walking on this kind of terrain as much as possible! Maybe if we had brought our trekking poles…

It wasn’t very busy up here, just a few small groups of people here and there.

The view of the Pnyx is better here compared to when we were a little bit further down in elevation.

Looking to the south, we could see the Philopappos Monument atop the Philopappou Hill.

There is actually a paved path on the southern edge of the Areopagus. This is the path that leads up from the normal entrance which is right below us here on the right.

We walked forward a bit on the path as much as we could.

These are the stairs that normally provide access to the Areopagus.

We started heading back down the west side of the hill. Out of the three hills near the Acropollis, this is the one to skip. The other two have very good views. The differing perspective from each of them makes them both worthwhile. The view here is basically a lower elevation view compared to the Pnyx and at a less interesting angle.

After returning to the bottom of the hill, we decided to get some ice cream from Fresko, which actually specializes in yogurt more than ice cream. We ordered mango and strawberry chocolate. It was a nice treat!

This cat was resting right by the shop.

Back to Syntagma

We decided to walk back to Syntagma as we haven’t done that yet from here. It isn’t too far.

When we visited the Pnyx, prior to ascending the hill, we walked by to the west of the Sanctuary of Zeus when we were at the Church of Agia Marina. That sanctuary is here at these rocks.

A sign explains:

Two early archaic (6th century B.C.) retrograde inscriptions, "HOROS" boundary and "HOROS AIOS" boundary of Zeus have led to the identify the visible remains on this projection of the Hill of the Nymphs (St. Marina) as the earliest known sanctuary of Zeus in Attica.

According to the literary sources and the archaeological evidence the worship of Zeus seems to prevail in the area around the Pnyx. Furthermore, the cult of the father of gods and men is strongly related with several other deities (Nymphs, Muses, Eileithyia, Artemis), which had their sanctuaries in the same area.

The main area of the sanctuary in the center of the foothill correlates with the inscription and the neighboring rock-cut structure with a drainage channel as its circumference is compatible with an altar for the god. In the south this area is bounded by a grooved road, to which the inscription "HOROS" is also though to refer.

The complex on the foothill is shaped into five rock-cut terraces, which function as a unit, being connected by stairs, while two entrances with carved staircases give access to the sanctuary from the south. On the surfaces of the five terraces the density of the drainage channels, rooms, wells, cisterns, and altars is Impressive; investigation has shown a continuous use of the area from archaic to post-Byzantine times.

The founding, in Byzantine times, within an ancient cistern, of the chapel of St. Marina as protectress of sick children is considered a continuity of ancient worship. The chapel preserves six superimposed series of wall-paintings dating from the 13th through the 18th century. In 1927 the elegant church of St. Marina was build, designed originally by Ernest Ziller.

In the custom of "Kylethra", in which women slide down the smooth rocks of St. Marina in order to ensure fertility, we see, even in recent times, the function, of Eileithyia and the Nymphs as goddesses of fecundity

Unfortunately, there isn’t really anything that can be seen here through the fence.

The opposite side of the path from the sanctuary has a nice view of the Acropolis through the fence which surrounds the Ancient Agora.

We decided to backtrack a bit to take the path that we saw along the southern boundary of the Ancient Agora when we were there. We had this view of the Lycabettus through the foliage after walking a short distance. The Stoa of Attalos, within the Ancient Agora, is visible here and almost seems like it is at the base of the Lycabettus.

We quickly reached the path we were looking for. It actually begins through the same open gate that we used to access the Areopagus. This area of the Ancient Agora, on the left side of the path, contains the State Prison were Socrates was held and drank the poison that ended his life.

So, here, the Ancient Agora is on the left and the Areopagus is on the right.

As we continued along the path to the east, both sides became lined with fencing. This was the portion of this path that we saw from the Ancient Agora.

We could still easily see and photograph over the fence though! Here, we can see the Acropolis to the southeast.

And, we are just a bit above the Ancient Agora to the north.

There are ruins to the south.

It didn’t take long to reach the end of the path. It seems like there was once a paved path that led south from there to the Acropolis. There is another path visible here in the background at the base of the Acropolis. This is the path we walked on when we walked from Monastiraki to the Philopappos Monument.

We looked through the fence to the northwest to see the southeastern corner of the Ancient Agora.

We continued on the path which leads to a small road. This road led to the east to the west end of the Roman Agora.

We found three cats at the southwestern corner of the Roman Agora site!

A wider angle view of the scene after the black cat got up and moved.

We walked to the north past the western edge of the Roman Agora and the Gate of Athena Archegetis.

At the northwestern corner of the Roman Agora, we turned right to walk along the northern edge of the site.

The road turned left, which led us to the southeastern corner of Hadrian’s Library.

The ruins of Hadrian’s Library extend to the south across the road we are walking on.

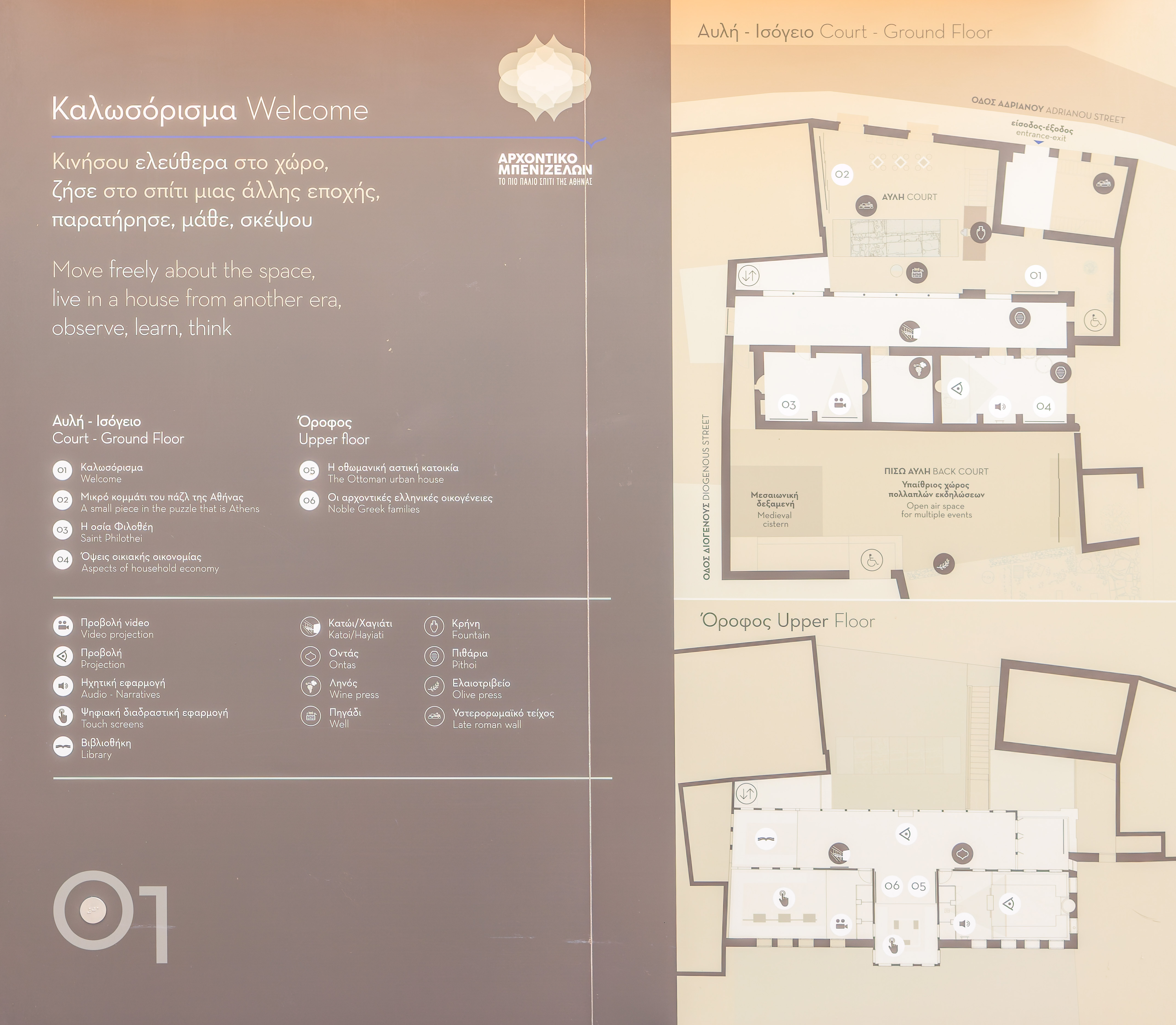

We followed the road to the east and ended up in front of the Benizelos Mansion. This is the only surviving konaki in Athens. This is a style of housing compound used by the wealthy in the Ottoman Empire.

Entrance is by donation with no mandated quantity.

This is one of two courtyards in this mansion. A small sign provides a short description:

One of the most important elements of mansions (archontika) of the period, the court is spacious with a garden and fruit trees. There are two courts in the konaki of the Benizelos family, one in the front and one in the rear of the house, interconnected via a narrow passageway.

Signs in this courtyard detail the history of Athens:

Early and Middle Byzantine period

After its destruction by the Heruli (267 AD), the city was initially limited to the area to the north of the Acropolis, protected by a new wall, called the Late Roman wall. Nevertheless, it quickly regained its previous extent (by the end of the 4th century), while the ancient wall was repaired and reused as an outer fortification enclosure until the late 12th century.

The city certainly loses its old glory when the philosophical schools closed (6th century). It is transformed into a provincial center that is gradually Christianized. Ancient monuments are converted to Christian churches. The numerous churches built beginning in the 9th century are records of a new period of prosperity in the city. A new fortification, called the Rizokastro, is also built around the Acropolis.

In 1154 the Arab geographer al-Idrisi describes the city as prosperous and populous. Pestilence, famine and pirate raids put an end to the prosperity of Byzantine Athens.

Frankish period

The city comes under the control of the Duchy of Athens, which has its seat in Thebes. Masters of the city: the French dukes De la Roche and Brienne (1204-1311), the Catalans (1311 -1387) and finally the Florentine house of Acciajuoli (1387 -1458). The settlement is greatly diminished, restricted to the area within the Late Roman wall and Rizokastro. When the Florentine rulers choose Athens for their residence, they install their palace on the Acropolis and restore the Orthodox metropolis to the city. At this time, Athens again sees intense building activity.

First Turkish period, 1456 - 1687 AD

Athens is a significant urban center of the empire. The Acropolis, the castle, is exclusively inhabited by Ottomans. The city, unfortified, extends once more outside the Late Roman wall. Mosques, hamams, tekkes, churches, monasteries, shops, houses and fountains find their places within the labyrinthine urban fabric, which is separated into eight sectors and 32 parishes or mahalle.

Indeed, from the second half of the 16th until the middle of the 17th century, the city sees notable demographic development - almost 18.000 residents have been recorded towards the end of the 16th century. The Greeks are superior in numbers, making up two thirds of the population. According to one account, 1.300 Greek, 600 Turkish, 150 Arvanite and 3 foreign households co-existed in the city.

Second Turkish period, 1687 - 1833 AD

Athens remains an important urban center of Central (Sterea) Greece and expands even further, acquiring 35 parishes. Administration buildings, mosques, tekkes, churches, schools, baths, shops, a clock tower and many mansions are visible within the urban fabric.

In 1778 the city acquires a new wall, the so-called "Haseki" wall, on the initiative of the Voevoda (governor) Hatzi Ali Haseki, renowned for his cruelty and greed. The city's economic development is particularly noticeable in the 18th century when the urban upper class becomes more powerful. In the late 18th century, approximately 8.000 to 9.000 residents are recorded as living in the city. The Greeks are always greater in number and socially superior.

The mansion had a well here and a cistern in the back, as described by a small sign atop the well:

Well

A well in the center of the court is a characteristic element of houses of the period. Notice the marks made by the rope on the marble mouth of the well. The house of the Benizelos family additionally had a cistern in the back court.

A sign describes evidence of an older house in an adjacent room:

Abstract rendering of elements of the older house