After breakfast, we checked out of the Excelsior Hotel Gallia and traveled to Venice. After dropping off our bags at the Hyatt Centric, we took a vaporetto via the east side of Venice and visited the Doge’s Palace before walking around the city and having dinner and gelato.

Leaving Milan

We scheduled a short visit to Milan as the city is well connected with non-stop flights to the US so we can easily return if we want to. So, after waking up at the Excelsior Hotel Gallia, we headed downstairs for breakfast.

Today is the Festa della Repubblica, the day where a referendum in 1946 decided the future of Italy after World War II. This marked the end of the Savoys and the Kingdom of Italy and the beginning of the modern Italian Republic.

They put out a little Italian flag as well as dishes of green, white, and red. These were not here yesterday.

Otherwise, breakfast was similar to yesterday.

After breakfast, we checked out and walked over to Milano Centrale to catch the next train to Venice.

We made our way to the vast hall where the train platforms are located.

The train we are taking today is one of Trenitalia‘s Frecciarossa trains. The trip takes less than two and a half hours, covering about 250 kilometers. Not particularly fast, particularly compared to the Shinkansen.

As the train departed, we saw a Swiss train on one of the platforms. In our limited experience with Italian trains, we’ve found that the seats are extremely close together. The Swiss trains are much more comfortable.

Arriving in Venice

We arrived at Venezia Santa Lucia, Venice’s main train station, not long after 11am. We headed right out with our bags to the Grand Canal to catch the next vaporetto to Murano, an island north of the main Venetian islands where the Hyatt Centric is located.

We dodged the access fee inspectors as it looked relatively time consuming to need to interact with them. As we are staying in a hotel within Venice, we have an exemption, though that needs to be registered on the access fee website.

While looking for the right quay to depart from, we spotted this vaporetto with a Shin Ramyun livery! Definitely unexpected! In the US, the cheap Nissin Cup Noodles are probably the most mainstream product. Shin Ramyun, a Korean product, is significantly higher quality. It probably isn’t too well known in the US though, despite it being pretty awesome for what it is. Is it mainstream here in Italy?

Locating the departure point was a bit confusing as there are a number of busy quays, each of which service a variety of routes and in both directions. There is digital signage that indicates the next few departures as well as signs indicating which lines are serviced by the particular quay. The individual quays at each terminal are indicated by letter suffixes, for example, Ferrovia D.

The most sensible way to get to Murano is to take the ACTV‘s Line 3, which goes to Murano without intermediate stops. If you take it in the correct direction! Line 3 stops at two different quays here, C and D, depending on the direction.

The ACTV is the main transit operator in Venice. They are enabled for credit card tap and pay, which is extremely convenient as a foreign tourist. Simply tap on before boarding at the quay and tap off after arriving. There are also other transport operators and various types of boats both large and small.

After getting off at Murano Colonna, we walked along a canal to the Hyatt Centric. This ended up being a very hot and slow walk, taking around 20 minutes with our luggage. We didn’t take any photos on the vaporetto or during the walk due to all the stuff we were carrying.

The Hyatt Centric is in a former glass factory and opened as a Hyatt in 2019. Before that, it was the LaGare Hotel Venezia – MGallery by Sofitel, part of Accor, according to a few early posts in the hotel’s FlyerTalk thread.

Our room was not ready when we arrived. So, after reorganizing a bit, we left our bags with the hotel and headed back out. One thing we realized is that there is actually a ferry stop right here in front of the hotel, Murano Museo. While we were aware that there were ferry quays here, we didn’t realize Line 3 came here.

We decided to travel to the main tourist area of Venice around the Piazza San Marco. In particular, we were thinking of visiting the Palazzo Ducale, often referred to as the Doge’s Palace in English. While entry generally requires timed tickets, it is also possible to buy a multiple-day pass which can enter at any time.

There are two passes available, one is the MUVE Museum Pass and the other option is the Venezia Unica City Pass. The Museum Pass allows a single entry to each of the museums within a 6 month period. The City Pass provides access to some of the same museums but is more expensive. They do have a San Marco specific pass that is more or less the same price as the Museum Pass but it only allows visiting the Doge’s Palace on the first day of validity. We opted for the Museum Pass.

We caught the next vaporetto to arrive to head back to the main Venetian islands, which we probably should just refer to as Venice. We could see the Hyatt Centric fade into the background as we pulled away.

We passed by the Murano Colonna stop where we had gotten off earlier. It gets its name from the column by the ferry quays.

There are various industrial buildings here in Murano, many of them involved in the glassmaking business. We don’t know what the function is of this particular building though.

Its a bit hard to tell but there are various channels for boats set up in the waters of the Venetian Lagoon.

Up ahead, we could see a smaller island. This is the Isola di San Michele. It contains a church, the Monastero di San Michele di Murano, as well as a cemetery which occupies most of the space.

After passing San Michele, we approached the north side of Venice.

We got off the vaporetto at Fondamenta Nove (F.te Nove). We started to walk to the east along the north shore of Venice.

We walked past canals on our right.

There was even a hospital with ambulance boats! This does make sense as there isn’t really any other way to quickly get around. Other than using a helicopter, of course, but there probably aren’t too many suitable landing zones here on these densely structured islands.

We decided to hop on a ferry at the Ospedale quay, just past the hospital. Some of the ferry lines have a decimal number indicating their direction. Line 4.2, for instance, rotates clockwise around the outer edge of Venice. This is the ferry we took. Walking would have been faster but this would allow us to get a good overview of Venice.

Resoluti

An ambulance boat sped by as we headed east on our much slower vaporetto.

About 20 minutes later, we could see the San Marco area ahead in the distance.

We passed by a much larger car ferry going in the opposite direction.

The Italian frigate F594 Alpino was docked nearby. Interestingly, the Wikipedia page for the ship currently has a photo of it docked in Baltimore back in 2018!

The north and east sides of Venice were pretty quiet with very little traffic. Here, it was much busier!

To the south, we could see the island of San Giorgio Maggiore with its church of the same name and tower. We got off the vaporetto at S. Marco-San Zaccaria, just opposite of the island.

This monument with equestrian statue on top honors Vittorio Emanuele II. They seem to really like their first king, despite having kicked the Savoys out after World War II.

Looking to the west, we could see the Palazzo Ducale (Doge’s Palace) on the other side of a canal. The term doge, ducale in Italian, comes from the local Venetian language and is a local term specifically for an elected city-state leader. While it sounds like the term might be equivalent to a duke, it is quite different as doges are elected.

We were rather surprised to see a banner for Non-Belief, an exhibition hosted by the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts at the Taiwan Pavilion for the Biennale Architettura 2025. So, what is it about?

The page for the exhibition on the La Biennale di Venezia website states:

Do you believe?

TSMC Chips, high speed, and the pursuit of efficiency have become Taiwan's “beliefs”, driving and transforming the world's operations. NON-Belief offers embodied Taiwan intelligens in architecture, examining and understanding how life adapts and transforms to establish a resilient and self-sustaining island republic in our collectively precarious future.

We read Taiwan Island’s built environment as comprising localised assemblages of digitally connected, democratically paradoxical contact zones. Taiwan Intelligens of Precarity locates these assembled worlds as comprising a front line in planetary resistance to authoritarian autocracy and adaptation to climate change at the Biennale.

What does this actually mean? We have no idea.

We saw many people photographing from the bridge that goes over the canal on the east side of the Doge’s Palace. The bridge over the canal is the Ponte della Paglia and the bridge we see between buildings on either side of the canal is the famous more than 400 year old Ponte dei Sospiri (Bridge of Sighs).

The story here is that prisoners would pass through this bridge from the Doge’s Palace to the prison on the other side of the canal after they were convicted. While passing through this bridge, they would get their final view of Venice. This name seems to have been made famous by the British poet Lord Bryon. Some sources credit him with coming up with the name, though it is unclear if that is true.

We walked around the Doge’s Palace to see the Campanile di San Marco in front of us. This tower is the tallest structure in Venice.

These two columns held sculptures on top. One is a man with spear and shield standing atop what seems like an alligator while the other depicts a winged lion.

Palazzo Ducale

After taking a quick look around, we headed over to enter the Doge’s Palace.

The columns in the covered walkway had some detailed elements carved into the stone.

After showing our digital tickets, we were able to enter. We’re not sure if there may be a queue during busier times, however, we were pretty much able to walk right in.

This chunk of carved stone depicts a winged lion, similar to the one atop the column outside.

Once inside, we were in a large courtyard. This type of area might possibly be referred to as a cloister, though that term is more often used for this type of area within a church. The Basilica di San Marco, which requires a separate ticket to enter, is on the north side.

A sign describes what we see here:

Having entered the Palace by the Porta del Frumento [Wheat Gateway], which is in the oldest, south-facing wing, one has the west-facing Piazzetta wing to one's left, and the east-facing Renaissance wing to one's right.

The north side of the courtyard is closed by the junction between the Palace and St. Mark's Basilica, which was the Doge's chapel. The small marble facade with clock (4) that stands there dates from rebuilding work in 1615. At the centre of the courtyard stand two vere da pozzo [wellheads] (5); massive and ornate works in cast bronze, they date from the middle of the sixteenth century.

The courtyard facads of the two oldest wings are simple and severe, whilst the Renaissance wing facade is much more ornate, and culminates towards the far end in the Giant's Staircase (6). Used for formal entrances into the Palace, this is guarded by two colossal statues of Mars and Neptune which were produced by Sansovino in 1565 and symbolise Venice's power on both land and sea. Designed by Antonio Rizzo, the staircase is near the Arch (7) commissioned by Doge Francesco Foscari (1423 - 1457); with a rounded vault and decorated with alternate bands of Istrian stone and red Verona marble, this veritable triumphal archway (8) links up with the Porta della Carta (Paper Gateway) through which modern-day visitors leave the Palace.

To the right of the Giants' Staircase is the Senators' Courtyard (9), where the members of the Senate gathered before government meetings. On the same wing of the Palace, but at the opposite end to the Giants' Staircase, the wide Censor's Staircase (10) rises from under the arcades to the loggia floor above. Built in 1525, perhaps to designs by Scarpagnino, this is where one's visit to the upper floors begins.

We walked up to the second floor to enter the museum area.

A sign here describes the loggias on the 2nd floor, the area where we are now:

The loggias enfold three sides of the building - east, south and west - offering atmospheric views of both the inner courtyard and the Piazzetta to the side of the Palace. They are also the feature which creates that extraordinary sense of lightness in the outside appearence of the building. Today, the fourteenth-century wing of the loggia-floor houses the Superintendence for Venice's Architectural and Environmental Heritage, whilst the Renaissance wing houses some of the offices of the museum's bookshop.

The route of the visit takes one from the Censors' Staircase to the Golden Staircase, which leads to the upper floors, by way of this Renaissance wing. Various state government offices were located here; and in the walls are set a number of bocche di leone [Lion's Mouths], the characteristic lion-head letterboxes through which, from the sixteenth century onwards, it was possible to post anonymous denunciations of crimes or misdeeds. On the other side of the lion's mouth, the denunciation fell into a wooden box which opened directly into the office responsible for the matter concerned.

It should be pointed out that only very rarely did the government act on such accusations, and only after careful investigation. Two plaques here are also worthy of note. One fourteenth-century plaque (1362) with Gothic lettering dates from the papacy of Urban V and promises Indulgences to those who give alms to the incarcerated; the other plaque stands opposite the head of the Giant's Staircase and can be most easily seen at the end of the visit; a refined piece of work by Alessandro Vittoria, it commemorates the visit to Venice by the French king Henry III in 1574.

There is quite a bit of basically illegible text here!

Kind of creepy.

We entered the Scala d’Oro, the Stairs of Gold, or more eloquently, Golden Staircase. The reason for the name is obvious!

A sign goes into some detail about these stairs:

The name of the Golden Staircase is due to the rich decoration of the vault in white stucco and 24-carat gold, upon which Alessandro Vittoria began work in 1557; the frescoed compartments in the decoration are by Giambattista Franco.

Commissioned from the architect Jacopo Sansovino in 1555 by the Doge Andrea Gritti, whose armorial bearings can be seen on the large archway, the Staircase was finally completed by Scarpagnino in 1559.

This was the ceremonial staircase that led up to the Doge's apartments and to the chambers in which the main bodies of state government met. Its sumptuous entranceway is surmounted by two marble sculptures: on the right, Atlas bearing up the Vault of the Heavens; on the left Hercules Slaying the Hydra. Both are the work of Tiziano Aspetti (sixteenth century).

The first ramp of the staircase is dedicated to Venus - an allusion to Venice's conquest of the island of Cyprus, birthplace of the goddess.

The stairs then fork into two ramps. The one of the right leads towards the Doge's apartments and is decorated with motifs referring to Neptune, and thus to Venice's mastery over the seas. In both cases, mythology is put to the service of the Republic and its celebration of itself.

The series of rooms at the top of the stairs is the Institutional Chambers. For Americans, this is the 3rd floor. For Europeans, the 2nd.

Institutional Chambers:

Here begins the long series of Institutional Chambers within the Palace, those rooms which housed the highest levels of a political and administrative system that was the object of widespread admiration for centuries. The very immutability of the system was amazing: without any written constitution as such, it was efficient enough to last over time and guarantee social peace. After the mid 1300s, the city was entirely free from riot or rebellion, and no one questioned the rights and abilities which enabled the city's aristocracy to monopolise management of the State; in fact, the regime symbolised by the Lion of St. Mark enjoyed extraordinary popular support and skilfully nurtured the myth of itself.

These chambers housed not only all the main organs of government within the Republic - from the Great Council, to the Senate and the more restricted Full Council - but also the most important bodies for the administration of justice, from the Council of Ten to the three Councils of Forty.

In each of the rooms, the decoration is always a throughly-planned celebration of the virtues of the State and the functions of government to be performed there.

This first room that we entered was the Square Atrium. Because it is a square room…

Square Atrium:

The room served largely as a waiting-room, the antechamber to all the various halls of government. The decoration dates from the sixteenth century, during the period of Doge Girolamo Priùli, who appears in Tintoretto's ceiling painting with the symbols of his office and accompanied by allegories of Justice and Peace.

The four scenes around, probably by Tintoretto's workshop, comprise biblical stories - perhaps an allusion to the virtues of the Doge - and allegories of the four seasons.

The celebratory decor of the room was completed by four paintings of mythological scenes by Tintoretto which now hang in the antechamber to the Hall of the Full Council. Their place here has been taken by Girolamo Bassano's The Angel appearing to the Shepherds and other biblical scenes that are, with reservations, attributed to Veronese.

Normally, the next room would be the Room of the Four Doors, however, it was closed for restoration activities.

So, the next room on our route was the Antechamber to the Hall of the Full Council. There was also some work being done here up above. There was netting in place, probably to prevent debris from falling into the lower part of the room.

Antechamber to the Hall of the Full Council:

This was the formal antechamber where foreign ambassadors and delegations waited to be received by the Full Council, which was delegated by the Senate to deal with foreign affairs.

Like the previous room, this was restored after the 1574 fire and so its decor, with stucco-work and ceiling frescoes, is similar to what one finds in the Hall of Four Doors.

The central fresco - by Paolo Caliari, better known as Veronese - shows Venice distributing honours and rewards. The top of the walls is decorated with a fine frieze, and other sumptuous fittings include the fireplace between the windows - designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi and sculpted by Tiziano Aspetti around 1586 - and the fine doorway leading into the Hall of the Full Council, whose Corinthian columns bear a pediment surmounted by a marble sculpture showing the female figure of Venice resting on a lion and accompanied by allegories of Glory and Concord; the work is by Alessandro Vittoria.

Next to the doorways are four canvases that Jacopo Tintoretto painted for the Square Atrium, but which were brought here in 1716 to replace the original leather wall panelling. Each of the mythological scenes depicted is also an allegory of the Republic's wise government.

The Antechamber contains other famous works, including Paolo Veronese's The Rape of Europe.

The next room we entered was the very impressive Council Chamber, the meeting room of the Full Council. It is, perhaps, more impressive than anything we’ve seen to date.

Council Chamber:

The Pien Collegio [Full Council] which met in this room was comprised of two separate and independent organs of power, the Savi and the Signoria. The former was in its turn divided into the Savi del Consiglio, who concerned themselves mainly with foreign policy; the Savi di Terraferma, responsible for matters linked with Venice's empire in mainland Italy; and the Savi agli Ordini, who dealt with maritime issues. The Signoria itself was made up of the three Heads of the Councils of Forty and of the members of the so-called Minor Consiglio (which consisted of the Doge and six councillors, one for each of the sestieri - districts - into which the city of Venice is divided). The Full Council was mainly responsible for organising and coordinating the work of the Senate, reading dispatches from ambassadors and city governors, receiving foreign delegations and promoting other political and legislative activity. The decor was designed by Andrea Palladio to replace that destroyed in the 1574 fire; and the wood panelling of the walls and end tribune - together with the carved ceiling - are the work of Francesco Bello and Andrea da Faenza. The splendid paintings set into that ceiling were commissioned from Paolo Veronese, who completed them between 1575 and 1578. This ceiling is one of the artist's masterpieces and celebrates the Good Government of the Republic, together with the Faith on which it rests and the Virtues that guide and strengthen it. The first rectangular panel shows the bell-tower of St. Mark's behind the figures of Mars and Neptune, Lords of War and the Sea. The central panel shows the Triumph of Faith, and the rectangular panel closest to the tribune, Venice with Justice and Peace.

Around there are some eight smaller, T-or L-shaped, panels that depict the virtues of government. The large canvas over the tribune is again by Paolo Veronese, and was produced in celebration of the Christian fleet's victory over the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto on 7 October 1571 - a victory to which the men and ships of Venice made an essential contribution. The rest of the paintings in here are by Tintoretto and his studio; they show various doges with Christ, the Virgin and saints.

This next room, the Senate Chamber, was also very large and very ornate.

Senate Chamber:

This hall was also known as the Sala dei Pregadi, because the doge "prayed" the members of the Senate to take part in the meetings held here. The Senate which met in this chamber was one of the oldest public institutions in Venice; it had first been founded in the thirteenth century and then gradually evolved over time, until by the sixteenth century it was the body mainly responsible for overseeing political and financial affairs in such areas as manufacturing industries, trade and foreign policy. In effect, it was a more limited sub-committee of the Great Council.

The refurbishment after the 1574 fire took place during the 1580s, and once the new ceiling had been completed work started on the pictorial decoration, which seems to have been finished by 1595. In the works produced for this room by Tintoretto and his studio, Christ is clearly the predominant figure. The room also contains four votive paintings by Jacopo Palma il Giovane which are linked with specific events in Venetian history.

This pair of windows was in between rooms.

The next room we entered, again just as ornate as the previous two, was the Chamber of the Council of Tens.

Chamber of the Council of Tens:

The Council of Ten that gives this room its name was set up after a conspiracy in 1310, when Bajamonte Tiepolo and other noblemen tried to overthrow the institutions of the State. Initially meant as a provisional body to try those conspirators, the Council of Ten is one of those many examples of Venetian institutions which were intended to be temporary but ended up becoming permanent. Its authority covered all sectors of public life - from religious orthodoxy to foreign policy, from espionage to state security - and this range of powers gave rise to the legend of the Council as a ruthless, all-seeing tribunal at the service of the ruling oligarchy, a court whose sentences were handed down rapidly after hearings held in secret.

The assembly was made up of ten members chosen from the Senate and elected by the Great Council. These ten sat in council with the Doge and his six counsellors, which accounts for the seventeen semicircular outlines that one can still see in the chamber. The decoration of the ceiling was the work of Giovanni Battista Ponchino, with the assistance of a young Paolo Veronese and Giovanni Battista Zelotti. Carved and gilded, the ceiling is divided into twenty-five compartments decorated with images of divinities and allegories intended to illustrate the power of the Council of Ten, which - like the court of Heaven - was responsible for punishing the wicked and freeing the innocent. It is very difficult to interpret each individual compartment because the artists often tend to overlap the traditional interpretation of a mythological event or figure with a reading that is specific to Venice and its history.

The paintings of Veronese - from that of the old oriental figure to that showing Juno scattering her gifts on Venice - are particularly famous. The oval in the centre, showing Jove descending from the clouds to hurl thunderbolts at Vice, is however a copy of the Veronese original, which Napoleon had taken to the Louvre.

The view from a window.

We then walked into the Sala della Bussola – Compass Room. Again, it is very ornate.

Compass Room:

This is the first room on this floor dedicated to the administration of justice; its name comes from the large wooden compass (bussola) surmounted by a statue of Justice which stands in one corner and hides the entrance to the rooms of the three Heads of the Council of Ten and the State Inquisitors (which can only be visited as part of the Secret Itineraries tour). This room therefore was the antechamber where those who had been summoned by these powerful magistrates waited to be called; and the magnificent decor was intended to underline the solemnity of the Republic's legal machinery, some of the most famous and efficient components of which were housed in these rooms.

The decor dates from the sixteenth century. and once again it was Paolo Veronese who was commissioned to decorate the ceiling. Completed in 1554, the works he produced are all intended to exalt the "good government" of the Venetian Republic; the central panel, with St. Mark descending to crown the three Theological Virtues, is however a copy of the original, now in the Louvre.

The large fireplace was designed by Jacopo Sansovino in 1553-54.

Within the Palace, all the rooms which served in the exercise of justice were linked vertically. From the ground-floor prisons known as The Wells, to the Advocate's Offices on the loggia floor, the Councils of Forty and the Hall of the Magistrates of Law on the first floor and the various courtrooms on this second floor, the progression culminated in the prisons directly under the roof, the famous Piombi or "Leads". All of these spaces were interconnected by stairways, corridors and vestibules.

From this room, in fact, one can pass to the Armoury and the New Prisons, on the other side of the Bridge of Sighs.

We next passed through some displays of weaponry in the Armory. There’s even a Gatling Gun!

The windows here provided views to the southeast, the area where we arrived by vaporetto.

We next walked into the Liago, more of a corridor than an actual room, described in English as the Liago Gallery.

Liago Gallery:

In Venetian dialect a liagò is a terrace or veranda enclosed by glass.

This particular example was a sort of corridor and meeting-place for patrician members of the Great Council in the intervals between their discussions of government business. The ceiling of painted and gilded beams dates from the middle of the sixteenth century, whilst the paintings on the walls are seventeenth- and eighteenth-century.

The next room was the Quarantia Civil Vecchia, the chambers of the Council of Forty.

Chamber of the Quarantia Civil Vecchia:

Here the itinerary continues with a visit to the rooms in which justice was administered.

The Quarantia [Council of Forty] seems to have been set up by the Great Council at the end of the twelfth century and was the highest appeal court in the Republic. Originally a single forty-man council which wielded substantial political and legislative power, the Quarantia was during the course of the fifteenth century divided into three separate Councils: the Quarantia Criminal (for sentences in what we would call criminal law); the Quarantia Civil Vecchia (for civil actions within Venice) and the Quarantia Civil Nuovo (for civil actions within the Republic's mainland territories).

This room was restored in the seventeenth century; the fresco fragment to the right of the entrance is the only remnant of the original decor. The paintings hanging here date from the seventeenth century as well.

The fresco remnant described on the sign for this room as the only remnant of the original decor of this room is right here behind a wooden access panel.

Guests at the Palace:

Vittorio Emanuele Bressanin

(Musile di Piave, 1860 - Venezia, 1941)

The Last Senate of the Republic of Venice

Oil on canvas

Venice, Museo Correr, Cl. I n.1994

THE ARTIST

Vittorio Bressanin is a painter originally from the Venetian mainland. He moved to Venice to attend the Academy of Fine Arts, where he was a student of Pompeo Marino Molmenti. He specialised in history painting and distinguished himself as an heir to the 18th-century Venetian tradition of frescoed decoration, which he interpreted with "sumptuous ease" (L. Bénédite).

He first gained notoriety at the 1887 National Art Exhibition in Venice with the painting on display here, which was purchased by the famous Venetian scholar Pompeo Gherardo Molmenti, Marino's nephew (Bressanin's teacher), who was a supporter of young artists and also made an important bequest to the Museo Correr.

Bressanin also exhibited at the 1894 Milan Triennale, where he won the Prince Umberto prize, at five editions of the Venice Biennale (1897, 1899, 1901, 1907, 1922); and at the Esposizione Nazionale in Rome in 1911. The Galleria Internazionale d'Arte Moderna di Ca' Pesaro houses nine of his paintings.

THE PAINTING

On May 12, 1797, with Napoleon's troops lined up for an attack on the shores of the lagoon, the Great Council of Venice met for the last time and abdicated in favour of a revolutionary government controlled by the French military command. On May 15, 1797, the last doge Ludovico Manin left the Palazzo Ducale forever. That was how the thousand-year-old history of the Republic of Venice ended.

Ninety years later, in 1887, Vittorio Bressanin wished to convey the powerful meaning of those events with this painting. An elderly senator descends the Giants' Staircase in the Palazzo Ducale. His heavy steps and lowered gaze show dignity and resignation. The old-fashioned wig and the famous red gown, which distinguished the magistrates of the Pregadi (the members of the Venetian senate) from all the other patricians of Venice, now belonged to a bygone era, the agony of which can be felt in the contrast between the external pomp and the historical reality.

In the interpretation of the nineteenth-century painter, we do not read decadence, but a reflection on the intimate drama stoically experienced by the magistrate, who here becomes a symbol of the entire city.

Continuing on, the next room was the Guariento Room. This room contains the remnants of huge frescoes from the 14th century.

Armamento Room or Guariento Room

Armamento Room or Guariento Room | Salle de Guariento

GUARIENTO DI ARPO

(Padua, active 1338 - 1367)

CORONATION OF VIRGIN know as PARADISO, 1365-1366

Fresco (detached 1905)

Venice, Doge's Palace, The Guariento Room

Partly because of the increase in the size of the Great Council in 1297, it was decided that there should be a radical reorganisation of the south wing of the Doge's Palace, which housed the government of the Republic. Ultimately giving the building the appearance we see today, work would begin in 1340 and continue for a long time. In 1365, the commission for the decoration of east wall of the new, enlarged Great Council Chamber went to Guariento. In the service of the Da Carrara family who ruled Padua, he was an artist known for his opulent Gothic style and for erudite compositions rich in theological, philosophical and literary references.

Soon famous for the splendour of its colours and its dazzling gold and silver decorations, the great fresco he produced centred around the figure of the Virgin, seated on a Gothic throne and being crowned by Christ (1). Below were seated the four Evangelists (2), with angel musicians beneath them (3). To the sides of the Evangelists were angels bearing lilies (4) or an orb and sceptre (5). To the left of the throne were the Cherubim (6), blue-winged and holding wheels in their hands; to the right were the red-winged Seraphim (7). Beyond these angelic hierarchies were two lines of seated saints - perhaps Prophets and Patriarchs - holding cartouches in their hands (8). Behind them stood more angels in armour (9) or bearing sceptre, orb and crown (10). Then followed a further two rows of seated saints holding books (11), behind whom were the relevant orders of the angelic host (12). A further two rows of saints with angels (13) has been lost entirely; in fact, all nine choirs of the angelic host were depicted, in strict observance of their place in the heavenly hierarchy. At the ends of the entire composition, two aedicules (14 and 15) contained the figures of the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin of the Annunciation. The entire work contained a number of features which underlined the parallel between the divine hierarchy of Heaven and that to be seen in the Council which met in this Chamber: the Virgin's throne was placed to correspond to the seat occupied by the doge; the lines of seated saints echoed the benches along the length of the chamber occupied by the councillors; the depiction of the Annunciation recalled that the city was traditionally believed to have been founded on the feast day of the Annunciation (25 March) in 421; the identification of the city with the Virgin Mary emphasised Venice's triumphant role in the world. The extant fragments of the fresco were discovered in the Great Council Chamber when Tintoretto's canvas was removed from the wall in 1903.

They were then transferred to canvas; thorough restoration, in 1995/1996, further improved their state of preservation.

This room, the Chamber of the Great Council. can be described as huge. And it is indeed the largest room in the Doge’s Palace.

Chamber of the Great Council:

53 metres long and 25 wide, this is not only the largest and most majestic chamber in the Doge's Palace but also one of the largest rooms in Europe. Here were held the meetings of the Maggior Consiglio [Great Council], the most important political body in the Republic. A very ancient institution, this Council was made up of all the male members of patrician Venetian families, irrespective of their individual status, merits or wealth. This was why, in spite of the restrictions in its powers which the Senate introduced over the centuries, the Great Council continued to be seen as bastion of republican equality - equality amongst aristocrats, that is.

The Council had the right to call to account all the other authorities and bodies of the State when it seemed that their powers were getting excessive and needed to be trimmed. The 1,200 to 2,000 noblemen who sat in the Council always considered themselves as the guardians of the laws which were the basis of all the other authorities within the State. Every Sunday, when the bell of St. Mark's rang, the council members would gather together in the hall, with the Doge presiding at the centre of the podium and his councillors occupying double rows of seats that ran, back-to-back, the entire length of the room.

This room also housed the first phases in the election of a new Doge, which in the later stages would pass into the Sala dello Scrutinio. These voting procedures were extremely long and complex, in order to frustrate any attempts at cheating. Restructured in the fourteenth century, the Chamber was decorated with a fresco by Guariento, the remains of which we have already seen, and later with works by the most famous artists of the period, including Gentile da Fabriano, Pisanello, Alvise Vivarini, Carpaccio, Bellini, Pordenone and Titian. When fire broke out in the Sala dello Scruinio next door in 1577, it also seriously damaged the structure of this chamber. Restoration work, maintaining the appaerance of the original chamber, was quickly completed; and decoration of the finished space involved such artists as Veronese, Tintoretto and Palma il Giovane. The walls were decorated with episodes from Venetian history, with particular reference to the city's relations with the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire, whilst the ceiling was decorated with the Virtues and individual examples of Venetian heroism, and a central panel containing an allegorical glorification of the Republic.

Facing each other in groups of six, the twelve wall paintings depict acts of valour or incidents of war that had occurred during the city's long history. Immediately below the ceiling runs a frieze with portraits of the first seventy-six doges (the portraits of the others are to be found in the Sala dello Scrutinio); commissioned from Jacopo Tintoretto, most of these paintings are in fact the work of his son, Domenico.

Each Doge holds a scroll bearing a reference to his most important achievements, whilst Doge Marin Faliero, who attempted a coup d'état in 1355, is represented simply by a black cloth (a traitor to the Republic, he was not only condemned to death but also damnatio memoriae, the total eradication of his memory and name). One of the long walls, behind the Doge's throne, is occupied by the longest canvas painting in the world, the Paradiso, which Jacopo Tintoretto and workshop produced between 1588 and 1592 to replace the Guariento fresco that had been damaged in the fire.

The room also contains three important works of sculpture: Adam, Eve and The Warrior. These are the originals produced to adorn the facades of the Foscari Gateway in the courtyard of the Palace. The work of Antonio Rizzo, they were sculpted between 1462 and 1471 and are masterpieces of realistic modelling and psychological insight.

The three important sculptures mentioned in the sign for this room are here. They depict, from left to right, Adam, The Warrior, and Even and were sculpted by Antonio Rizzo in the 15th century.

Statues:

Adam, Eve and Warrior (Mars), stunning masterpieces of the early Venetian Renaissance by Antonio Rizzo (c. 1430-40 .- c. 1499) are among some of the most important 15th century sculptures in Italy. The statues originally stood out in the open, in the niches on the middle section of the Foscari Arch: Eve on the right and Adam on the left of the east side façade, facing the staircase with the Giants by Sansovino; the Warrior (Mars) was instead the first sculpture on the south side of the Foscari Arch, facing the courtyard. The three sculptures were created for the Arch, but not all at the same time. Although their dating is not certain, they can be placed between 1470 and 1490.

The statues, of larger than natural dimensions, are made of Carrara marble.

In the Roman style, the Warrior (Mars) wears sandals, lorica armour with a skirt of leather lappets and metal plates and a cloak fastened on one side by a clasp. His face is exposed with his helmet raised and he leans on his rhomboid shield (the current design is a replacement from a nineteenth-century restoration).

Barefoot on a grass lawn, Adam leans against a tree trunk with numerous cut branches in the style of Mantegna and clutch the forbidden fruit in his hand and looks aloft in dialogue with the Almighty Father. Adam a sinewy, taut muscular mass and intensified, accurate anatomical study that bear traits of Paduan influence, but also have much in common with the physiognomies of Antonio Pollaiolo, something which suggests that Rizzo must have been to Florence at least once.

Eve seeks to cover her nudity, assuming the famous pose of the Venus pudica. The reference to the classical style is accentuated by the fact that Adam and Eve are the first monumental nudes of Venetian sculpture. Yet the body of Eve is not classical. It is instead heavily influenced by modern and Nordic models in its elongated proportions, narrow shoulders, long neck, wide hips, small head and graceful, elegant long hair (stylistic features that endured in countries North of Italy right up until the female figures of Lucas Cranach). Between Adam and Eve runs the headway and full formulation of Venetian Renaissance sculpture.

This smaller room is the Chamber of the Quarantia Civil Nuova, the judicial body that handled civil cases on the mainland rather than within the Venetian Lagoon.

Chamber of the Quarantia Civil Nuova:

Established in 1492, the Quarantia Civil Nuova was the judicial body responsible for civil cases on the mainland, unlike the Quarantia Civil Vecchia, which dealt with civil cases within the lagoon territories.

The current appearance of the room is due to the restoring and conserving interventions carried out after the fire of 1577.

The seventeenth-century allegorical paintings found in the upper part of the walls refer to the judicial skills of the Quarantia magistrates. On the walls you can admire the Lions of San Marco by Donato Bragadin and Jacobello del Fiore. The latter comes from the Magistrato alla Bestemmia [Magistrate of Blasphemy], a body established by the members of the feared Council of X, whose officials were responsible for judging crimes against religion, morality and good customs.

The next room, the Chamber of the Scrutinio, is large and ornate once again.

Chamber of the Scrutinio:

From this room one enters the fifteenth-century wing of the Palace, built during the reign of Doge Francesco Foscari. It was here that the precious codices which Petrarch and Cardinal Bessarion had left to the Republic were housed before the building of the Biblioteca Marciana. Thereafter, in 1532, it was decided to use this chamber for the voting procedures required by various state appointments, hence its present name.

The decor dates from 1578-1615. The richly-decorated ceiling was designed by the painter-cartographer Cristoforo Sorte and depicts Venetian naval victories in the East and the conquest of Padua in 1405.

The walls are decorated with various military victories over the period 809 to 1656; Andrea Vicentino's rendering of the Battle of Lepanto is particularly striking.

It may seem strange that a room destined to be used for voting purposes has a decor which exalts military might rather than political wisdom; but the whole scheme was carried out just after that victory of Lepanto, at a time when Venice's pride in its arms was at its greatest.

The frieze under the ceiling continues the series of portraits of Doges, whilst one of the shorter walls is decorated with a Last Judgement. Painted by Jacopo Palma il Giovane between 1587 and 1592, this could be seen as linked with the Paradiso in the Hall of the Great Council.

The Voting Chamber ends with a majestic triumphal arch. The work of Andrea Tirali, this was raised to commemorate Doge Francesco Morosini Peloponnesiaco, who died in 1694 during the successful campaign in which Venice took control of the Peloponnese from the Turks.

We passed through a corridor with windows on one side…

And headed into the Chamber of the Quarantia Criminale. This was the highest court in the Venetian Republic.

Chamber of the Quarantia Criminale:

Housing one of the three Councils of Forty, the highest appeal courts in the Venetian Republic, this is another room used in the administration of justice. The Quarantia Criminal was set up in the fifteenth century and, as the name suggests, dealt with cases of criminal law. It was a very important body as its members, who were part of the Senate as well, also had legislative powers. The wooden stalls date from the seventeenth century.

We immediately recognized this painting in the Cuoi Room as being in the style of Dutch painter Jheronimus Bosch. We had visited his hometown, Den Bosch, during our trip to Amsterdam last year and visited the Jheronimus Bosch Art Center.

Unfortunately, this painting, from the 16th century, is not by Jheronimus Bosch but is instead a painting in his style. The artist seems to be unknown.

This painting was in the Chamber of the Magistrato alle Leggi. It is Lion of Saint Mark by Vittore Carpaccio in the early 16th century. The winged lion, the Lion of Saint Mark, is a symbol of Saint Mark, the patron saint of Venice and thus a symbol of Venice.

Chamber of the Magistrato alle Leggi:

This chamber housed the Magistratura dei Conservatori ed esecutori delle leggi e ordini degli uffici di San Marco e di Rialto, to give them their full title. Created in 1553, this authority was headed by three of the city's patricians and was responsible for making sure the regulations concerning the practice of law were observed.

In a mercantile city such as Venice, the courts were of enormous importance (think, for example, of the amount of litigation, the number of court-cases, which must have arisen within such a huge market as the Rialto). And the administration of justice in the city was made all the more special by the fact that it was not based on Imperial, Common or Roman law but on a legal system that was peculiar to Venice.

This painting in the same room is Neptune Offering the Riches of the Sea to Venice by Giambattista Tiepolo in the 18th century.

Continuing on, we passed over the Bridge of Sighs into the prison area of the palazzo. This narrow bridge has two lanes, one for going in each direction. The windows here are small and unfortunately were very dirty during our visit. Photography on the Internet suggests that the windows are cleaned, we were simply unlucky.

These were actually taken while we were returning to the main part of the palazzo from the prison area, however, it makes sense to present them here.

There’s not really much to see in the prison section. It’s kind of like a tiny Alcatraz. After quickly walking through this section, we passed back over the Bridge of Sighs, taking the photos on the way that were presented above.

We then entered the Chamber of Censors.

Chamber of Censors:

The State Censors were set up in 1517 by Marco Foscari di Giovanni, a cousin of Doge Andrea Gritti and grandson of the great Francesco Foscari.

The title and duties of the Censors resulted from the cultural and political upheavals that are associated with Humanism. In fact, the Censors were not judges as such, but more like moral consultants - a role that is clear from the fact that they were only two in number, and thus incapable of giving a majority ruling. Their main task was the repression of electoral fraud and the protection of the State's public institutions. On the walls hang a number of Domenico Tintoretto's portraits of these magistrates, and below the armorial bearings of some of those who held the post.

The next room was the Chamber of the State Advocacies.

Chamber of the State Advocacies:

This particular State Advocacy department dates from 12th century. The three members - the Avogadori - were the figures who safeguarded the very principle of legality, making sure that the laws were applied correctly.

Though they never enjoyed the status and power of the Doge and the Council of Ten, the Avogadori remained one of the most prestigious authorities in Venice right up to the fall of the Republic. They were also responsible for preserving the integrity of the city's patrician class - that is, verifying the legitimacy of the aristocratic marriages and births inscribed in the Golden Book.

The room is decorated with paintings showing some of the Avogadori venerating the Virgin, the Risen Christ or various saints.

We then passed into the entrance to the Coffer Room.

Coffer Room:

The Venetian nobility as a caste came into existence because of the "closure" of admissions to the Great Council in 1297; however, it was only in the sixteenth century that formal measures were taken to introduce restrictions that protected the status of that aristocracy: marriages between noblefolk and commoners were forbidden, and greater controls were set up to check the validity of aristocratic titles, etc.

The enforcement of these restrictions came within the duties of the Avogaria di Comun, which was also responsible for drawing up the Golden Book, which registered the baptismal vows of each new-born patrician (if a baptism was not so registered, the aristocrat concerned risked finding himself excluded from the Great Council and thus from any role in the city's political life). It later became compulsory for each aristocrat to produce a marriage certificate before the Avogaria, irrespective of the social status of his wife.

There was also a Silver Book, which registered all those families that not only had the requisites of "civilisation" and "honour" but could also show that they were of ancient Venetian origin; such families furnished the manpower for the State bureaucracy - and particularly the chancellery within the Doge's Palace itself. The Golden and Silver Books were kept in a chest (scrigno) in this room, inside a cabinet that also contained all the documents proving the legitimacy of claims to be inscribed therein. The cabinet which one sees here nowadays extends around three sides of a wall niche; lacquered in white with gilded decorations, it dates from the eighteenth century.

The final room on the route through the Doge’s Palace was the Chamber of the Navy Captains.

Chamber of the Navy Captains:

Made up of twenty members from the Senate and the Great Council, the Milizia da Mar - first set up in the middle of the sixteenth century - was responsible for recruiting the crews necessary for Venice's war galleys. No easy task, given the large number of people required by the city's extensive fleet.

Contrary to what one might expect, the bulk of these crews were made up of paid oarsman drawn from the Venetian manufacturing industries - that is, from those various crafts and guilds which had a direct interest in preserving the city.

Another similar body, entitled the Provveditori all'armar, was responsible for the actual fitting and supplying of the fleet.

The furnishings and covered furniture are sixteenth-century, whilst the wall torches date from the eighteenth century.

The next room, now the Palace Bookshop, used to house the Lower Chancellery of the Doge's Palace.

Passing through there, you come out onto the loggia, opposite the Giants' Stairway.

Well, technically, the gift shop was the last room. We got a magnet and postcards.

Once we returned to the large courtyard outside, we went to take ac loser look at the two bronze well heads.

It looks the same as it did when we first arrived, other than the location of the Sun…

We went into a long and relatively narrow room to the side on the ground floor. This room was the Museum of the Opera. Other than the common modern usage of the word opera, this word can also mean work. This room was basically a maintenance facility for the palazzo, hence, the opera name.

Museum of the Opera:

The Opera, also known as the 'fabbriceria' (Works Office) or procuratoria (Procurators' Office), was a sort of technical office responsible for the maintenance of the Doge's Palace.

During the time of the Serenissima Republic, the care and maintenance of the building were under the jurisdiction of the Senate. In more recent times, one of the most significant restoration plans was launched in 1875, involving both the facades of the palace and the ancient capitals of the ground-floor portico and loggia. Forty-two of these capitals, particularly ancient, valuable, or fragile, were replaced with copies. The originals, stored in the palace, later underwent careful restoration, while a Museum of the Opera was designed and set up on the ground floor to house them with other important architectural relics of the Palace. The capitals displayed here are a valuable and important part of the extraordinary collection of sculptures and reliefs that adorn the medieval facades of the Doge's Palace.

Today, this room houses a variety of architectural elements from the palazzo.

This gondola was outside.

We walked to the north side of the courtyard to exit.

We spotted this sculpture by the exit. It may look familiar. It depicts Saint Theodore and was originally atop one of the two tall columns outside.

Statue of Saint Theodore:

"II Todaro"

the first Patron Saint of Venice

The statue depicting Saint Theodore of Amasea, the "Todaro", one of the most revered saints among the martyr soldiers of the East and patron saint of Venice before St. Mark, was originally on the top of the western column of Piazzetta San Marco, next to the column with the lion of St. Mark.

The statue is a pastiche of pieces from different eras and places: the head probably belonged to a colossal statue depicting Constantine, the bust belonged to a loricate statue of a Roman emperor, perhaps Hadrian; the other parts of the body and the dragon at its feet, similar to a crocodile, were added at the beginning of the fourteenth century. It is interesting to note the diversity of the materials used: the shield in Istrian stone; the legs, arms and dragon in Marmara marble (from the island of Marmarain the Sea of Marmara between the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea), the armour perhaps in lunense marble (Carrara marble named after the Port of Luni) or pentelic marble (from the quarry of the Mount Pentelicus, not far from Athens, also used for the Parthenon); and the head, which is in white marble from Docimium, near Afyon (today's Afyonkarahisar) in the western Turkey.

The dragon recalls the iconography of St. George, whose cult is traditionally linked to the protection against swamping and the healthiness of the air.

We didn’t see anything that discusses the winged lion atop the other column. It is referred to on some sources as the Lion of Venice. Its history is unclear but is believed to be made from pieces of other sculptures or may be a modified form of some other sculpture. Based on a recent study in 2024 at the University of Padua, it may be from the Tang Dynasty in China!

The Giants’ Staircase is right by the exit.

Giants’ Staircase:

We walked under this cherub to exit.

These four figures, on a corner of Saint Mark’s Basilica by the exit of the palazzo, caught our attention enough to photograph them. We didn’t see anything about them, however, they are the Four Tetrarchs. They depict four Roman emperors and were created around 300 AD. They are believed to be from Constantinople, now Istanbul, but ended up here in the early 13th century.

There’s that winged lion again!

The northwest corner column of the Palazzo Ducale. It’s incredibly detailed!

The Campanile di San Marco can be visited, though it is not included with the MUVE Museum Pass. We may or may not visit on this trip, we’ll see if we do!

Although the Basilica di San Marco is also not included with the Museum Pass, we do plan on visiting, just not today.

This building from the 15th century is the Torre dell’Orologio (Clock Tower). It is a civic museum and can be visited.

A Stroll Through Venice

By now, it was 5pm. A bit early for dinner by Italian standards but we were pretty hungry as we did not have lunch. So, we decided to eat somewhere nearby. There were a few options in the area that looked promising. We ended up going to La Piazza, a few confusing blocks to the north. As this is Venice, we intend to eat as much seafood as we can while we’re here!

Both dishes that we ordered were excellent! The squid ink pasta was better than the ones we’ve had before, including yesterday in Milano. The lobster was also excellent and very flavorful! It was basically a half lobster, though smaller than a Maine lobster.

After dinner, we started walking the labyrinthine paths of Venice, intending to ultimately end up on the north side of the island to catch a vaporetto back to Murano.

Of course, we had to get gelato on the way. We stopped at Gallonetto, which had a queue outside and currently holds a 4.9 rating on Google Maps.

Luckily, the queue didn’t take too long. We got strawberry, pistachio, chocolate fondant. The flavors were excellent!

We continued on, turning to the west on a small detour to see the Rialto Bridge.

We noticed this shop, Nino and Friends, with its interesting chocolate display. Just as we were ready to walk away, it started to pour. We had rain gear but it was raining extremely hard. So, we ended up going into this shop to wait out the rain and to take a look. The staff were friendly and extremely generous with samples.

We ended up getting some snacks. They had quite a bit that we could have bought, however, much of it had limited expiration dates and some would not have been acceptable to bring into the US.

It was still lightly raining when we headed back out to continue walking to the west.

We decided to get more gelato, this time from Suso. They also had a queue and some interesting flavors that aren’t typical of Italian gelato shops that we’ve been to.. We got:

MENTACIOK - Mint and chocolate chips

GRAEKOS - Yogurt ice cream with passion fruit pulp

PISTACCHIO ASSOLUTO - Selection of premium pistachios

DARK CIOK - Pure dark chocolate cream with no milk. Intense flavour.

We continued on, still to the west.

We soon arrived at the Rialto Bridge. This is perhaps the most famous bridge in Venice and was built in the late 16th century to replace an earlier wooden bridge. It was the only crossing of the Grand Canal until the mid-19th century.

The view from the bridge looking in both directions. There’s the Shin Ramyun vaporetto again!

The view looking back to the east from the north side of the bridge.

Both sides of the bridge are actually lined with small shops.

The Rialto Bridge, as seen from the northeast. We didn’t cross as that would have meant a much longer walk for us. We could have just caught a vaporetto but we’ll save a trip down the Grand Canal for another day.

We started walking to the north.

We briefly went in to see the interior of a small church, the Chiesa di San Giovanni Grisostomo (Church of Saint John Chrysostom). It was built in the 16th century..

We continued walking through the north. The area got more confusing as we continued.

We photographed a canal from both sides of a bridge here. But, we failed to take a more important photograph here, of the far side of the bridge to the northeast. It ends at the front door of a building! It was a dead end! There are bridges on either side of this one, we needed to backtrack and take one of them!

We ended up backtracking too far but eventually found our way to a different bridge. What will be on the other side? The narrow path between buildings and the turn ahead meant that we couldn’t see what was on the other side! GPS works poorly here due to all the narrow passageways and multi-story buildings.

Luckily, this was the bridge to the northwest of the one were were just on, seen here now to the southeast.

The view to the northwest.

This is probably the narrowest passageway that we walked through today!

We continued walking to the north…

We ended up at the F.te Nove quays. Looking to the north, from here we could see the Isola di San Michele (Saint Michael’s Island).

We boarded the next Line 4.1 to arrive. It was not busy.

The vaporetto departed F.te Nove…

And we passed by Saint Michael’s…

And continued on to Murano.

We checked in at the front desk again and got our room keys.

We also got some information about the hotel and a welcome letter.

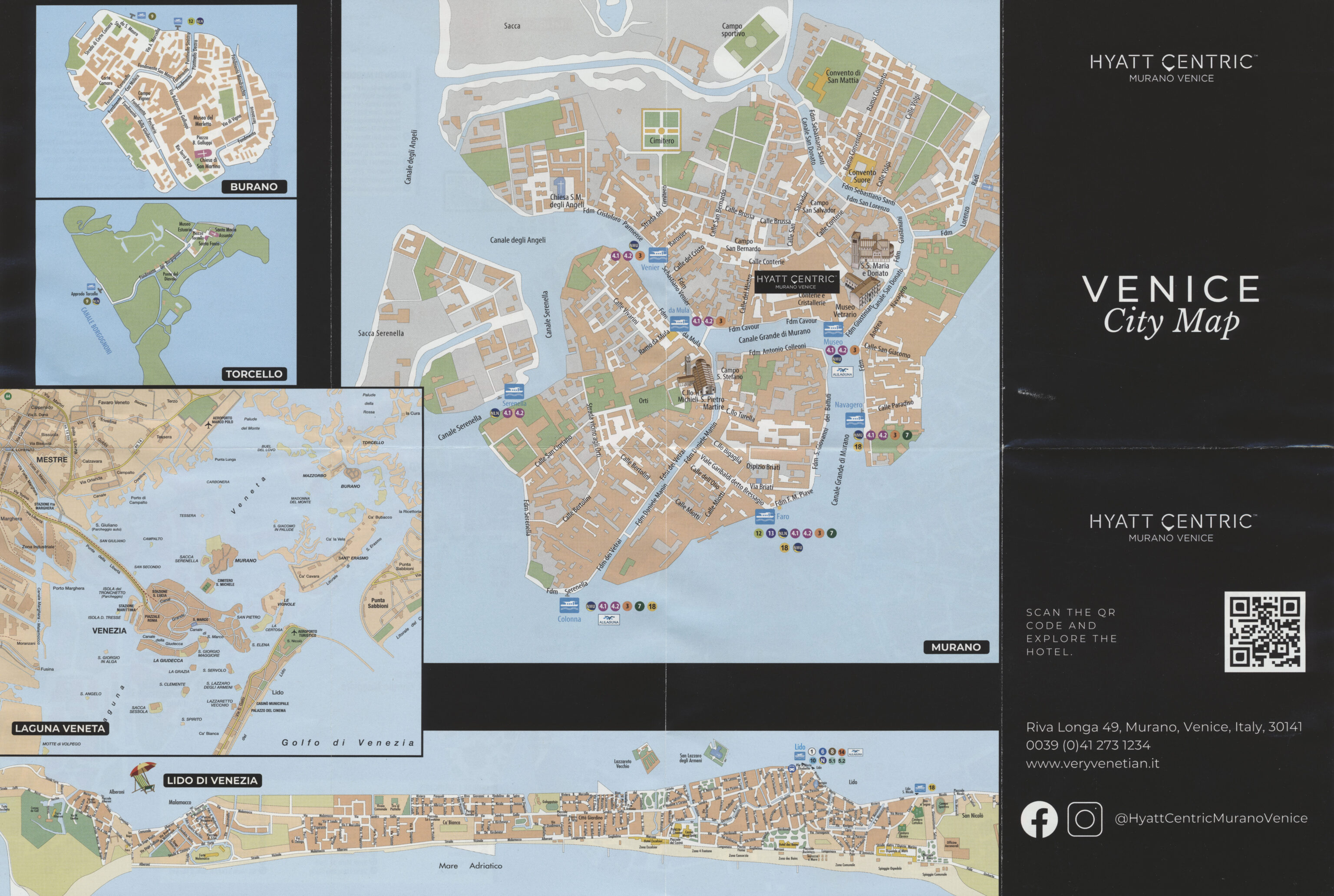

And, a detailed map of the Venice Lagoon.

Our room was pretty simple. It wasn’t too big but had enough room.

There were a few reasons why we picked this hotel over the other options. It was in a relatively convenient location with frequent vaporetto service as well as one that goes directly to the airport via Alilaguna, possibly the next largest transport operator here after ACTV. The Alilaguna service also runs early in the morning, which we will be useful as we have a morning flight out. The price was also cheaper than the other options we were looking at, and we were able to use a free night certificate for one of our three nights.

The bathroom was also simple but modern. Unfortunately, it did not have a tub.

The photos for this hotel are misleading in that most of the room types do show a tub in the bathroom, however, it is not in the room description for everything but the Grande Suite with Canal View. It is unclear if some rooms have a tub and some do not, or if the tubs are being phased out as they have been from many hotels.

The view is of the hotel’s restaurant. It ends up being a bit noisy in the evenings as a result as there is also a bar down there.