After breakfast at the Excelsior Hotel Gallia, we visited the interior of the Duomo and its museum. We had lunch, visited the Basilica di San Lorenzo Maggiore, and walked through the exterior of the Castello Sforzesco before dinner.

Morning

After waking up at the Excelsior Hotel Gallia, we headed downstairs for breakfast, which is complimentary as we are Titanium members in the Marriott Bonvoy program.

Breakfast at the Excelsior Hotel Gallia is mostly buffet style, though it is possible to order egg items such as an omelette. There was an ok selection with mostly pretty good dishes, though some things like the fruit weren’t as good as they could have been.

Duomo

After breakfast, we walked over to Milano Centrale to take the Metro down to the Duomo.

We were amused by this sign which had English indicating that we should walk on treadmills to reach the trains! This is a case where the the same phrase, tapis roulant, is used to mean a moving walkway and treadmill in Italian while in English we have different phrasing. Still, funny!

We caught the next Metro that was headed to the Duomo station.

Yesterday, this area was swarming with Inter Milano fans and part of it was fenced off due to a concert on the 30th of May. Today, everything was clear and open. We walked over to once again see the equestrian statue of Vittorio Emanuele II.

The magnificent Duomo!

There were two queues, one on either side of the front of the Duomo. The correct entry for us was on the right.

The line moved slowly due to ticket and security checks.

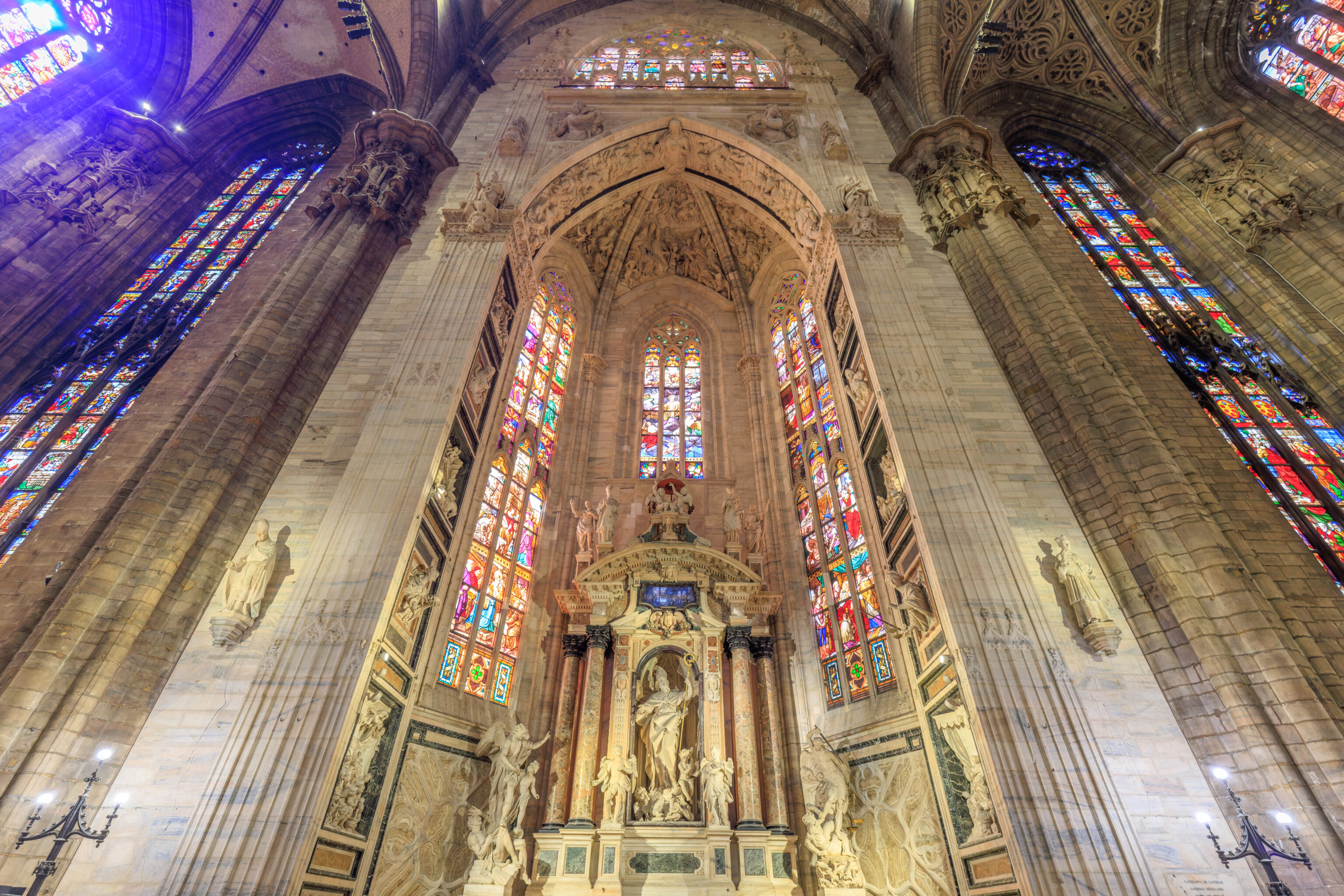

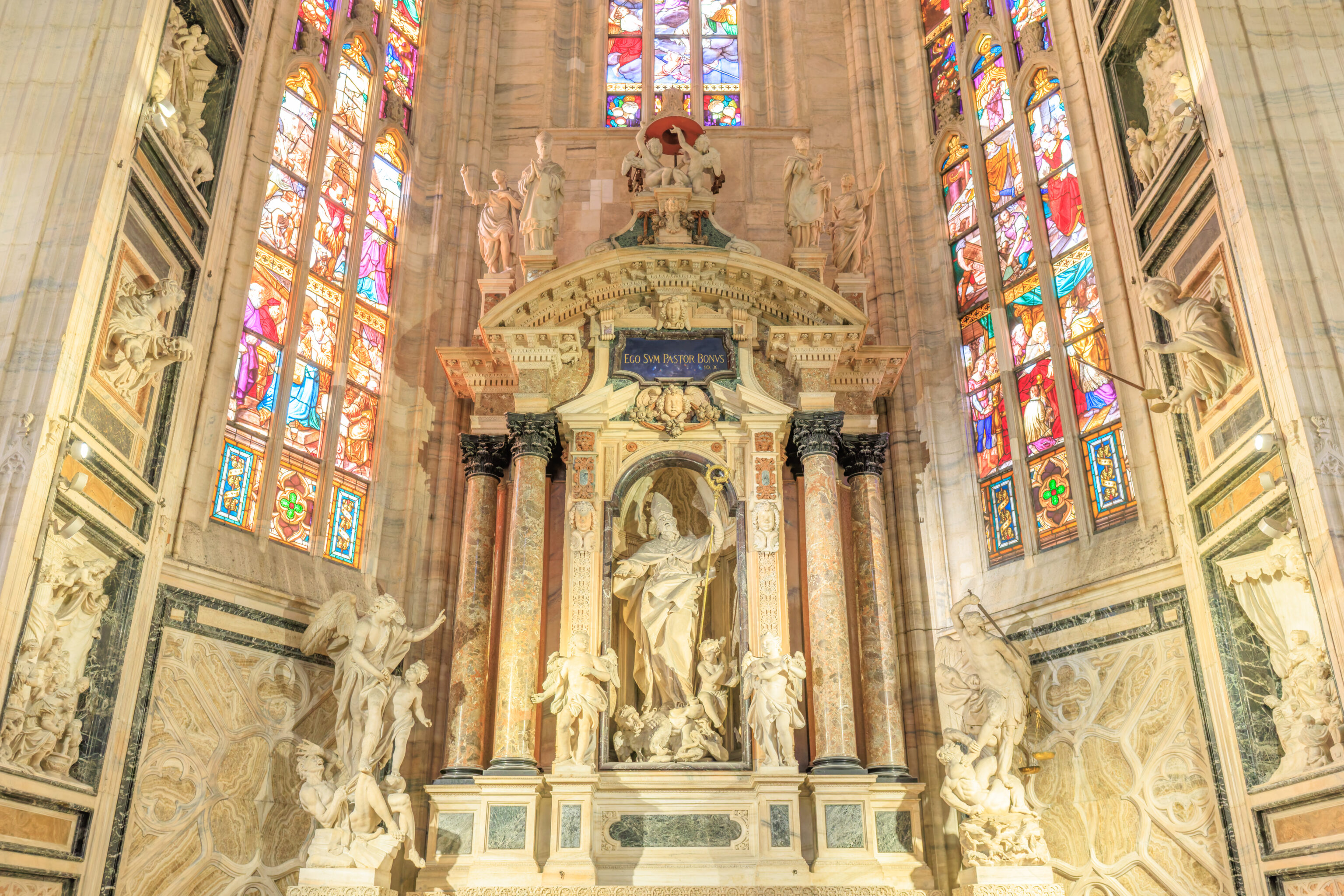

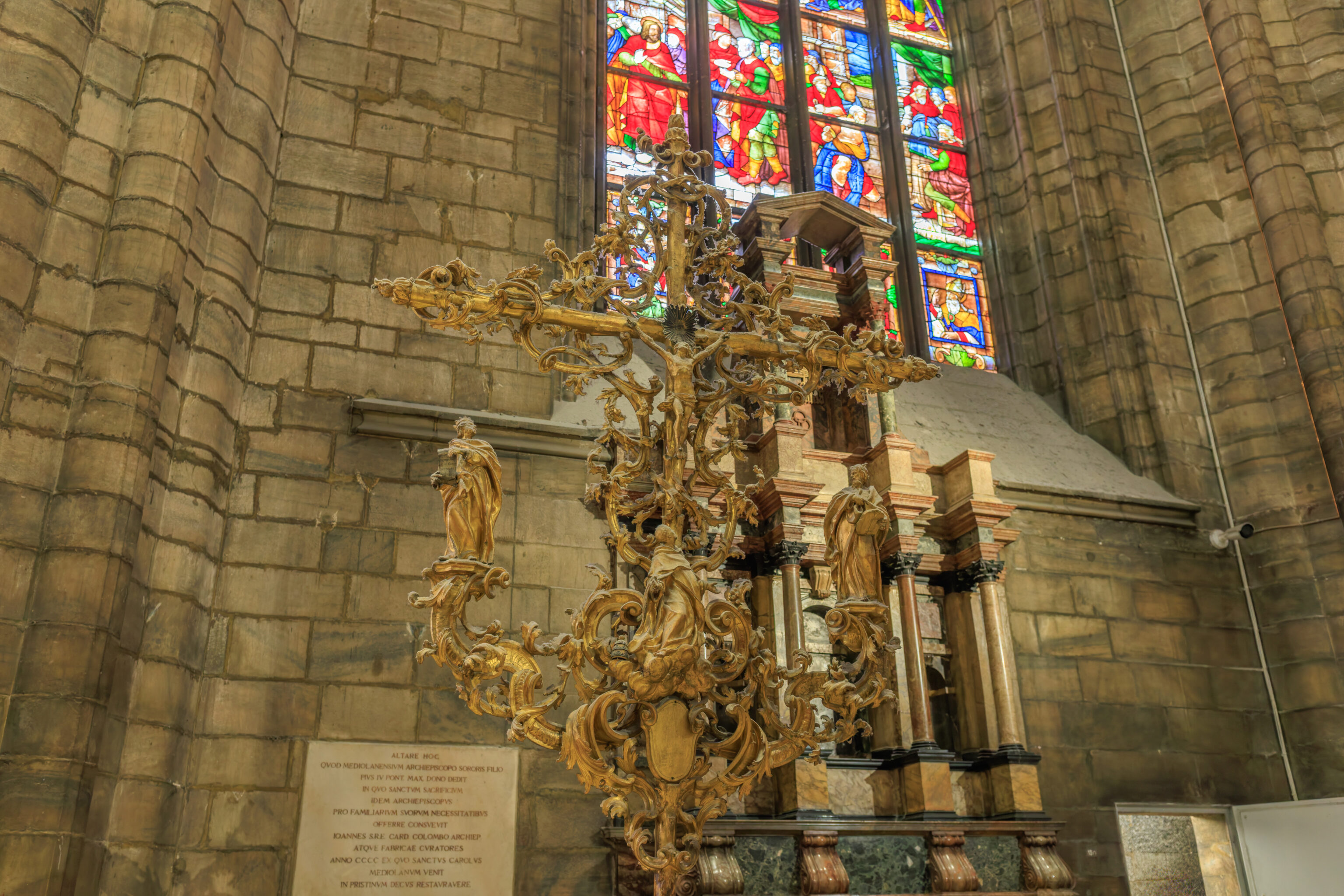

Soon, we were inside the vast interior of the Duomo. This huge structure is quite impressive on the inside due to its immense size. There is quite a bit of detail on the building, though overall it is not as ornate as some other cathedrals that we’ve been to.

There are, of course, stained glass windows.

This display lists all the archbishops of the current Archdiocese of Milan. The listing dates back to the year 51, though this cathedral was built in the late 14th century.

This is interesting as Christians were persecuted in the Roman Empire until Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313. Various sources such as Wikipedia indicate that Anathalon, the first bishop of Milan, lived during the 2nd or 3rd century. Other bishops on the list, for example, Ambrogio and the modern Cardinal Angelo Scola, do line up with modern references.

We saw Saint Ambrogio’s body yesterday at the Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio.

We spent quite a bit of time in the Duomo, looking through the vast interior and observing the Mass which was taking place in the front.

We recorded over an hour of video within the cathedral during our visit. The video is, unfortunately, rather dark compared to our photos. Oops. An editing fail which would be a bit time consuming to fix properly at this point.

Our ticket included entry into the archeological area below the cathedral. So, we went down to take a look.

Upon descending, we saw various ruins including walls and mosaiced floors.

Luckily, there are various signs in the archeological area that describe what we saw.

“The Rise in level of the Urban Surface to the south of the Baptistery between Antiquity and the Modern Age”

We now enter the area of the episcopal complex and return to the end of the 4th century when Ambrose had the Baptistery of San Giovanni alle Fonti built.

The rich stratification, preserved along the southern boundary of the archaeological area and approximately four metres in height under the old parvis (1942-1943), shows the development of this area of the city between the 1st and the 20th century; it also demonstrates both the progressive increase in height of the urban surface and the succession of buildings constructed during the Middle Ages where, previously, there had been open spaces.

The signs have both English and Italian. Unfortunately, the English is a subset of the Italian text.

“A Funerary Basilica”

Severely damaged by the construction of sewer-works in the 1800s, this building, paved in cocciopesto, was built to the south-west of the baptistery after the 6th century, probably in the Early Middle Ages.

The funerary purpose of the church has been documented by the presence of a burial site inside the main apse, discovered during the works of the 1960s.

During more recent works (1996) more tombs constructed by cutting the cocciopesto flooring, were found. A large structure, covered by a heavy serizzo stone slab, utilized several times, was probably a family tomb. A small ditch near the perimeter is all that remains of the grave of a new-born child.

The family tomb mentioned on the sign seems to be at the bottom of this photograph.

“A very precious Baptistery”

Thanks to the marble remains in situ and material found in the demolition layers, we can reconstruct the rich decoration inside the paleo-christian baptistery: polychrome mosaics in glass paste on the vault and upper part of the walls and costly panels inlaid with imported marbles and local stone on the lower part. The commissioning of these decorative works is attributed to urentius, Bishop of Milan from 489-510/512.

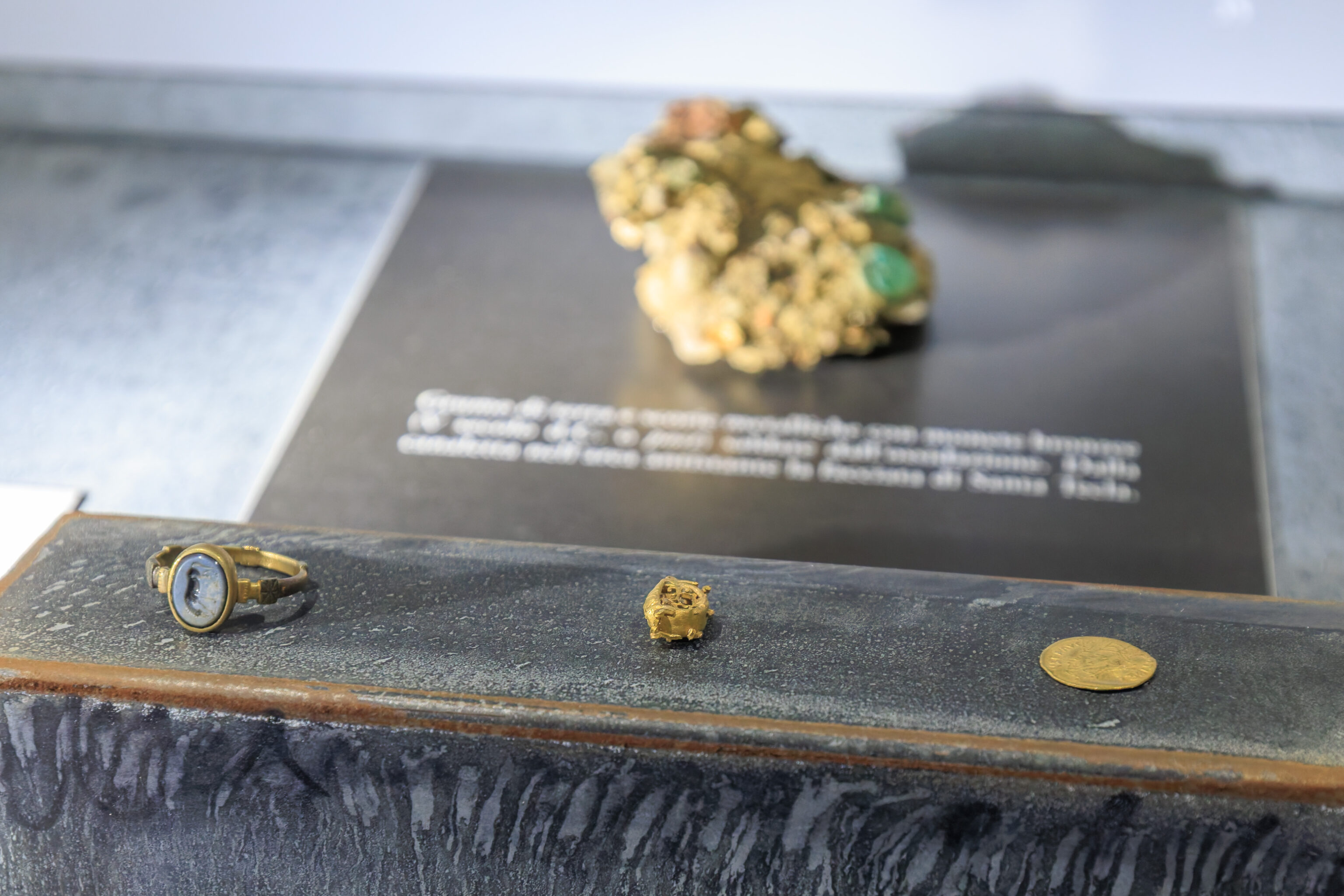

“The Baptismal Offering”

Inside the perimetric trench of the baptistery, 222 coins dating to between mid-4th-beginning 7th century were found. Passages by Church Fathers suggest several ways to interpret the function of the coin:

1. an offering for the healing of the soul from sin

2. a symbol of the passage from one condition to another

(death-life)

3. an amulet to keep demons away.

It sometimes wasn’t obvious exactly what the signs are referencing in terms of what we saw here in front of us.

There were various items discovered here on display.

“Inside Santa Tecla”

We are inside the apse of Santa Tecla (1st phase) where the imposing walls, with foundations in pebble conglomerate and vertical sections in brickwork which characterised the original floor plan of the great cathedral, can be recognised. Before its foundation, the whole area was densely built up.

Not only were there dwellings with heating systems, discovered under the apses but archaeological surveys have also revealed a sizeable building, presumably with a public function, in the area of the central nave and, slightly west of it, contexts of small dimensions and differing orientations.

We spent about 15 minutes walking through the archeological area before heading back up into the modern Duomo.

We ended up leaving at noon, having spent almost three hours inside the cathedral!

We went to find the Museo del Duomo. We came across this display which shows the time until the start of the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games. A neat feature of this display is that it snows inside. Obviously, not real snow, but it was a nice effect.

The entrance to the museum was just beyond this display, basically directly south of the entrance door to the Duomo that we queued at earlier in the morning.

The museum houses a vast collection of religious artifacts.

We arrived at a tiny courtyard on the south side of the museum.

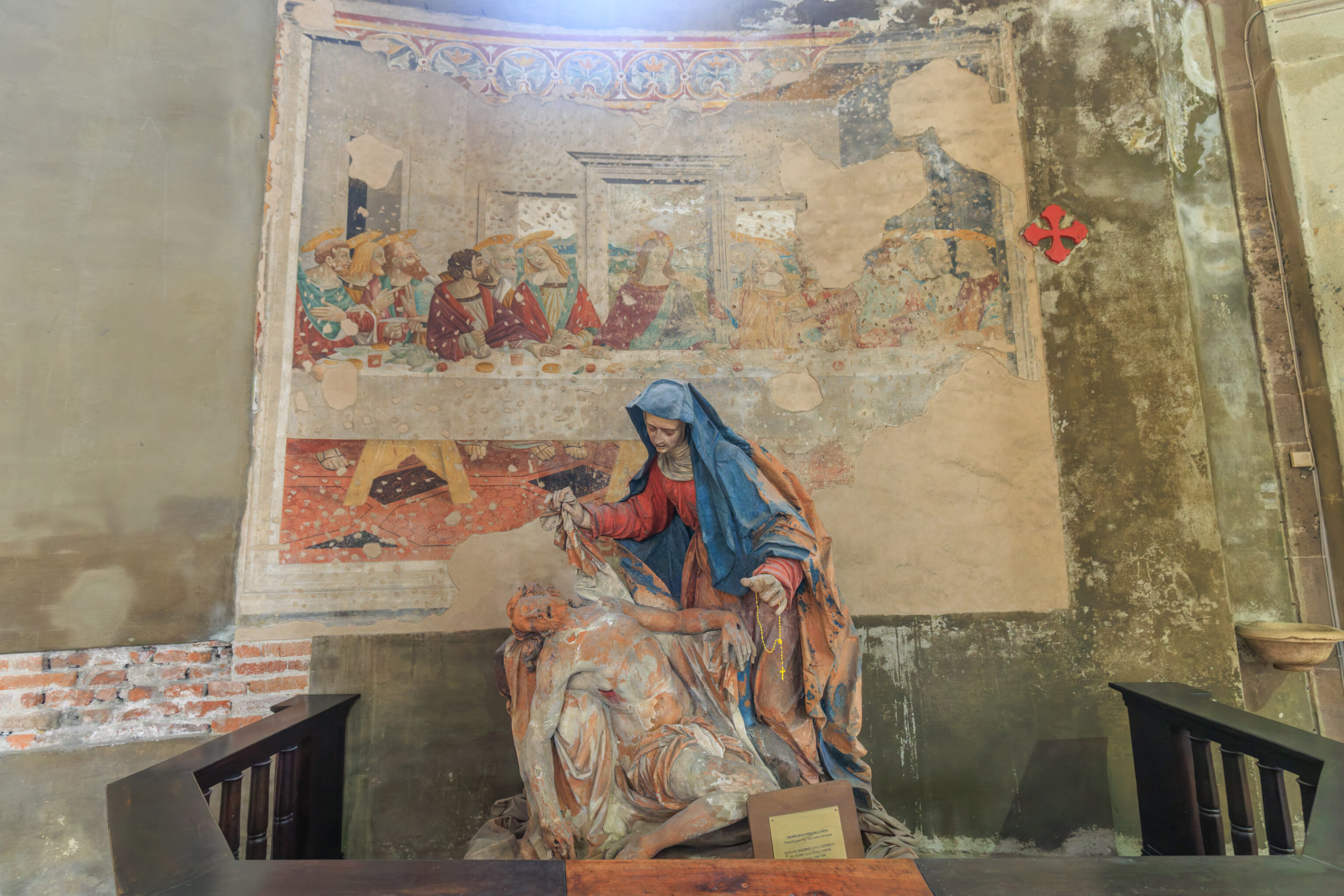

The courtyard led into the Chiesa di San Gottardo in Corte (Church of San Gottardo in Corte), a former chapel from the 14th century.

This damaged fresco from the 14th century was found in this church’s bell tower in 1926.

“The Crucifixion”

This extraordinary masterpiece from the Giotto School was discovered in 1926 during the renovation of an area adjacent to the Church. The fresco with the Crucifixion was found at the base of the bell tower, hidden beneath a thick layer of plaster that was later removed.

Conservation of the work outside the tower immediately presented significant issues, which is why it was removed and brought inside the church in 1953, where it is still visible today on the back wall of the nave. Though heavily damaged, the lower section of the work can still be appreciated: near the three crucifixes, a complex and fragmentary composition develops, with figures arranged on several levels, and the wings of angels that laterally invade the surrounding segments of the geometric design. Following the latest restoration, a feature of a cogwheel has re-emerged on the far right, thanks to which Saint Catherine of Alexandria can be identified, alongside maybe Catherine of Savoy-Vaud, wife of Azzone Visconti whose profile is positioned symmetrically on the left of the fresco.

The Master of San Gottardo, active around 1340 in the Palatine Chapel, used a revised style of contemporary Tuscan figurative culture, demonstrating that he had assimilated the lesson of Giotto, called by Azzone Visconti to work on the "old court" (today the Royal Palace) between 1335 and 1336.

We headed outside the church to take a look. We ended up at a completely fenced-in area.

We headed back in to complete walking through the museum and its vast collection of artifacts.

After we headed back out, we took one more look at the Duomo before continuing on.

Lunch

We decided to have lunch at Via Pasteria, a nearby restaurant. We took a tram to get there, which ended up taking longer than expected due to some trams still not running today. We ended up taking #15 from P.Za Fontana. We probably should have just walked!

We got off the tram at the C.So Italia Via S.Sofia stop. We came upon this column while walking north from the tram stop.

Just past the column, we spotted this church, the Basilica di Sant’Eufemia.

And, just beyond the church, we reached Via Pasteria. This particular restaurant is something like what we would consider fast casual in the US. You are first seated but then place your order at the counter.

Both dishes were excellent with great pasta and sauces. This small restaurant had unlimited free water which was quite nice as usually the only water options we’ve seen in Italy are overpriced.

Basilica di San Lorenzo Maggiore

We decided to walk to our next destination, the Basilica di San Lorenzo Maggiore, as it wasn’t too far to the west.

We walked past a winged lion.

We arrived at the rear of the basilica. There was a fence here so we decided to walk around to its front to the east via the north side, or counter-clockwise.

We arrived at this remnant of a brick gate. Or maybe this is the side of a building?

Beyond, we saw a line of columns as well as as a similar brick structure on the opposite side.

These columns are referred to as the Colonne di San Lorenzo. They are believed to be from the 1st century, or 2nd depending on the source, and were moved here in the 4th century.

The basilica was undergoing renovations. We weren’t sure if it was open.

We decided to check out the area to the south first. After walking past the columns, we saw that there was a gate beyond, the 12th century Porta Ticinese Medievale.

After walking to the piazza before the gate, we looked back to see the dome of the basilica.

Just past the Porta Ticinese Medievale, we visited VERO here for some gelato, seen here from two perspectives. We got mint & basil, coffee, strawberry, and apple & cinnamon. The apple & cinnamon was like a really good apple sauce!

From here, looking to the west, we saw a church, the Santuario di S. Maria della Vittoria.

The south side of the gate as we passed back through.

We returned to the the Basilica di San Lorenzo Maggiore to see if it was open. Outside, there is a statue of Emperor Constantine.

A nearby sign discusses the history of this basilica:

This central-plan church is of particular significance in the history of western architecture. It was built between the late 4th and early 5th centuries outside the city walls on the road to Ticinum (present-day Pavia), not far from the Roman circus and amphitheatre, from which the large stone blocks used for its foundations are thought to have been taken. It was probably a palatine basilica, linked to the nearby imperial palace, like San Vitale in Ravenna. Despite being extensively rebuilt after damage by fire and the collapse of the vault, it retained its original layout: a 24-metre-square hall with exedrae on the four sides (each pierced by five arches) and a surrounding ambulatory topped by matronea. The four square corner towers are designed to counteract the lateral thrust of the dome. Adjoining the main quatrefoil structure are three octagonal sacella of different sizes: to the south the Chapel of St. Aquilinus, a 4th-century imperial mausoleum with semicircular and rectangular niches, an umbrella domě and a vestibule (some of the remarkable original mosaic decorations survive); to the east the Chapel of St. Hippolytus, a Greek-cross martyrium with a hemi-spherical dome, built to contain the remains of saints Lawrence and Hippolytus; and to the north the Chapel of St. Sixtus, similar to but slightly smaller than the mausoleum of St. Aquilinus and with a square atrium. The basilica was radically remodelled twice: in the late 11th and early 12th centuries in the Romanesque style, and in the 16th century by Martino Bassi, who created the large octagonal dome, set on a tall drum decorated with paired pilaster strips.

The basilica was open! We headed inside to take a look. A small sign inside provided a bit more information about this basilica:

The basilica of San Lorenzo was probably built at the beginning of the VIth Century, though it was often altered over time. When the dome collapsed in 1573 it was replaced by an octagonal dome. In the early XVIIth Century construction began on the two rectories. The facade was completed in 1894. The main church features a central square plan. The chapels and sacristy radiate from the ambulatory around the perimeter. The sixteen columns that led to the original four-sided peristyle are still standing in front of the basilica complex. Of the original Early Christian decoration, the mosaics of the chapel of Sant'Aquilino and the frescoes in the matroneum are still visible.

We saw that members of the congregation were setting up inside the basilica. Interestingly, they were all Filipino. A bit of Googling reveals that this is likely the Filipino Community of San Lorenzo with nearly 500 members.

We walked through the basilica, looking at some of the elements on the sides of the interior.

A sign goes into a history lesson about this church and Milan:

Milan

Milan, one of the most important cities in the Roman Empire and strategic junction in the communication routes to the North, became the Imperial Seat of the Western Empire; here, in 313 A.D., the Emperor Constantine issued the edict granting freedom of worship to Christians. Due to mounting pressure along the borders by the Visigoths who, led by Alaric, besieged the city in 401 A.D., the Imperial Seat was transferred to Ravenna in 402 A.D .; during the following centuries, Milan was sacked several times by the barbarians crossing the peninsula. The most serious was carried out by the Goths in 539 A.D.

When the Longobards conquered the territory in 569 A.D., they made Pavia their capital as it was situated in an area easier to defend.

It was only during the Carolingian period that Milan regained its role as an important, vital centre thanks to its bishops who, in the power vacuum which had been created, had acquired ever-increasing religious prestige and political power.

The Basilica

In the 4th century, San Lorenzo was erected outside the city walls, not far from the amphitheatre, the Imperial Palace and the circus, along the Ticinensis road which linked Pavia to Milan and thus was the most important access road of the city. People arriving in Milan saw the mass of the Basilica as "the most imposing building of central symmetry of Western Christendom"(M. Mirabella Roberti)

1500 years ago, entering San Lorenzo

The Basilica, built on an artificial hill, was and still is comprised of a building with a central floor plan, delineated by four towers and, around it, three small satellite buildings with an octagonal floor plan. Entry was through a four-sided portico which was preceded by a colonnaded entrance.

On the western side, three doorways opened on to a square hall inscribed inside a tetraconchoid composed of four exedras; each of these was semi-circular, lined with 4 columns on the inside and on the outside, by curving masonry. Then, as now, a deambulatorium or walkway followed the inside perimeter of the central hall and, above it, there was a loggia, the original function of which is not known but which came to be used as a women's gallery over the following centuries.

Opposite the wall of the entrance (towards East), the Basilica extended into a chapel designed with a Greek-cross floor plan inside an octagonal perimeter which was successively dedicated to St. Hippolytus. Four doorways opened out from the side of the chapel. Two, under the towers, became the entrances to two absidal rooms which were probably built in the 6th century. From the right exedra (towards South), through an atrium, one entered an octagonal building (probably the Imperial mausoleum but incorrectly identified as a baptistery) which is the present-day chapel of St. Aquilinus. Between 489 and 511 A.D., Bishop Laurence I had the chapel of St. Sixtus built on the north side, symmetrical with that of St. Aquilinus, for the tombs of bishops.

A series of wide windows illuminated the lower part of the Basilica and similar openings were made in the lower part of the towers. It is reasonable to assume that the lower part of the walls was faced in marble while the vaults, the arches and the higher parts were decorated with mosaics.

The Basilica was constructed with material recovered from pre existing buildings, a practise which became widespread from the 3rd century onwards, due to the economic crisis which also affected the business activity of quarries. For example, material recovered from the nearby amphitheatre was used for the foundations, a 1st century doorway was used in the St. Aquilinus chapel and the columns in front of the Basilica came from a 2nd century building.

The same sign also had a panel discussing the columns that we saw outside:

The Columns of San Lorenzo

The sixteen columns of Musso-Olgiasca marble, 7.60 metres tall, were placed there, where they still are, perhaps during the construction of the Basilica as the entrance to a probable four-sided, Late Antiquity (end 4th century) portico. They were recovered from a 2nd century building.

At the present day, the colonnade stands on a Mediaeval plinth and the central intercolumniation, surmounted by a baluster dates to this period as well, probably added as part of rebuilding works between the 11th and 12th centuries.

Over the centuries, the houses built between the Basilica and the columns isolated them from their architectonic context and placed them at continual risk of demolition: in 1548, they were already under threat when the road was widened for the entry of Phillip II, King of Spain. The danger of demolition occurred again during the following centuries: at the end of 1700 when they were defended by the illustrious Pietro Verri and again in 1830 during the new layout of Corso di Porta Ticinese.

By the beginning of 1900, the principle of conservation became established and in 1933, demolition of the buildings between the colonnade and the Basilica started, thus restoring their visual unity.

Due firstly to the heavy bombing of August 1943 and then the vibrations caused by passing trams, a difficult and immense restoration of the columns became necessary in the post-war period.

Another sign goes into further detail about this basilica:

The Origins of the Basilica

As the date of construction cannot be defined precisely (see Chronology, Panel 1) theories regarding its origin oscillate between mid-4th century and the beginning of the 5th century, a period characterised by important historical changes.

Scholars agree on its Imperial origins for the following reasons:

· The architectonic model differs from the basilica-type construction preferred by St. Ambrose in Milan;

· The massive dimensions and original design of the "tetraconchoid" architectonic complex with its "double-frame";

· Massive costs involved;

· The use of materials recovered from pre-existing public buildings probably including the nearby amphitheatre.

The archaeological surveys of 2002-2004 defined the date of construction as between the last decade of the 4th century and the beginning of the 5th century, that is, during the final years of the Emperor Theodosius and the period of Honorius and Stilicone. If this were the case, the building would have been constructed to demonstrate the stability of the Theodosian dynasty and to reinforce the role of Milan as Imperial Residence during an historically difficult period due to the pressure of the barbarians along the borders of the Empire.

However, the purpose of such a vast complex is yet to be clarified. The hypothesis of it being an Imperial church arose from its presumed proximity to the Imperial Palace and the tetraconchoid floor-plan would have been intrinsic to the court ceremonies introduced by Theodosius. However, the most accepted theory is that it was a vast ceremonial area, both civic and religious related to the Imperial Mausoleum, the present-day chapel of St. Aquilinus (according to Mediaeval tradition, chapel of the Queen, related to Galla Placidia, daughter of Theodosius).

Another theory suggests that the whole complex was designed as a mausoleum for the Imperial family of Stilicone, and his assassination in 408 A.D. would have shrouded both commissioner and building in silence. In either case, the added civic function would justify the four towers which give the structure the appearance of a fortress. In opposition to these theories, however, it can be noted that the building was constructed according to a single plan and despite the temporary departure of Honorius for Ravenna in 402 A.D., work was not interrupted; it is therefore doubtful that such a costly undertaking would have been commissioned and completed by an Imperial Court planning to leave Milan. If this were the case, advancing its dating, the older hypothesis of equating San Lorenzo with the Portiana basilica, given to the Arians by the Emperor and never identified except for its location outside the walls, cannot be excluded.

The uniqueness of its construction raised questions even in Mediaeval times when it was considered to have been either a pagan temple or a thermal building.

We were not able to visit all the interior areas of the basilica as one section was closed off, possibly due to whatever event the congregants were preparing for, maybe mass?

We headed back outside, briefly resting on some seating underneath a tree.

We started to head to the De Amicis Metro station to the west.

On the way with a slight detour, we stopped by Gelateria LAB. We got matcha, lemon, 85% dark chocolate, pistachio & salt. The matcha was better than expected given that we haven’t really seen matcha in Italy. It was a bit too sweet but still had more matcha flavor than we expected.

A bust by the station.

Ruins were recently discovered here during station construction in 2016. They were moved to accommodate the station and o display here.

“San Gerolamo Canal Embankment: The Redevelopment Project”

SECTION OF THE SOUTHERN/OUTER EMBANKMENT/QUAYSIDE OF THE SAN GEROLAMO NAVIGLIO

Discovered in 2016 in Piazza Resistenza Partigiana, the section of San Gerolamo canal's external bank / quayside witnesses the enormous works carried out starting from the 14th century in order to transform the medieval defensive moat into a navigable canal inside the complex system of the Navigli, which allowed to connect Milan with rivers and lakes of Northern Italy and, therefore, with the Mediterranean and Northern Europe.

To allow the construction of the De Amicis station and preserve the material evidence of the artefact, the masonry was broken down into 16 pieces and for a while placed in the Metroblu base camp in via Cavriana. Once the station was completed, in 2024 it was repositioned and recomposed in a dedicated niche, reproducing its original orientation and height.

Passing by it while walking through the station hall, you can admire it from the same point of view as those who travelled along the Naviglio di San Gerolamo on one of the many boats that sailed it from the 13th until the middle of the 19th century, when the closure of the so-called Fossa Interna del Naviglio was decreed.

Castello Sforzesco

We took the Metro over to Cadorna Station, which we passed through yesterday. Looking to the northeast, we could see the outer wall of the Castello Sforzesco. We saw the castle from this perspective yesterday, however, did not approach any further.

We walked up to the castle’s wall and took a look around the immediate area. It was pretty hot and we ended up sitting on a bench in the shade for awhile.

This tower, at the southern corner of the castle’s wall, shows the historic coat of arms of the Visconti of Milan, former dukes of Milan, depicting the biscione.

We passed through the gate underneath another the coat of arms of the House of Sforza, which includes the biscione. They were the subsequent dukes of Milan after the Visconti.

This castle is home to Michelangelo’s Pietà Rondanini, the incomplete sculpture that he was working on at the time of his death.

These signs describe this sculpture in various languages, including English:

The Pietà Rondanini

by Michelangelo

Since 1952, Milan has been home to the last sculpture produced by Michelangelo Buonarroti, who was born in Caprese in the province of Arezzo, in 1475, and died in Rome in 1564. The work was unfinished at the death of the artist, who worked on this block of marble for over a decade. It represents the Madonna, on her feet, supporting the dead body of her son Jesus after the Crucifixion. The two figures are very elongated, almost thread-like, and far removed from the physical power with which Michelangelo's creations are usually endowed. In the block of marble there are some traces of a previous version, where the characters had a more robust anatomy. The dramatic intensity of the relationship between Mother and Son, almost fused into a single body, should be seen in the light of Michelangelo's profound religiousness.

The artist tackled the theme of the Pietà several times, with different techniques and solutions: starting at least from the work now in the basilica of Saint Peter's in the Vatican, when Michelangelo was twenty-five and was pursuing a completely different idea of beauty, with the healthy-looking body of Christ on the knees of an adolescent Mary. At over eighty years of age, he reduced everything to the essential, drawing on a medieval iconographic scheme.

The vicissitudes of the Milan Pieto are still shrouded in considerable mystery: the sculpture was in Michelangelo's Rome workshop when he died on 18 February 1564. Subsequently, it disappeared and only resurfaced with certainty in 1807 in the palazzo of the marchesi Rondinini (or, less properly, Rondanini) in via del Corso - hence the name by which the work is known: the Rondanini Pietà. After several changes in the ownership of the Roman palazzo, the sculpture was purchased, thanks also to a public raising of funds, by the City of Milan in 1952. In the meantime the style of the work, long ignored and considered marginal to Michelangelo's output, won over critics and contemporary artists, and the Rondanini Pietà, a unique piece of sixteenth- century sculpture, acquired a privileged position in art history.

In 1956, Michelangelo's Pietà went on display, in a celebrated exhibition layout designed by the Milanese studio BBPR, in the Sala degli Scarlioni of the Sforza Castle: a vast room packed with Lombard Renaissance sculptures - in particular by Bambaia - modified greatly over the years and with difficulties of access for the disabled. Hence the decision of the city council to devote an independent space to Michelangelo's work - the former hospital in the castle's courtyard of arms, which, in the period of Spanish dominion, treated sick soldiers. Since 2 May 2015, this space, which has witnessed a great deal of suffering and of prayer, has been home to Michelangelo's Pietà, in a layout designed by Michele De Lucchi.

While in the Vatican Museums, we saw casts of the three Michelangelo Pietà sculptures, including the one here. Unfortunately, even if we could get tickets right now, it is closing time for the museums here.

We walked around this section of the castle within its outer walls.

We walked through a passageway to the northwest, ending up here in this much smaller courtyard, the Rocchetta Courtyard. The word rocchetta here is presumably used to mean small castle.

“The Restored Rocchetta”

THE RESTORED ROCCHETTA

The extensive works carried out on the Castle in 2012 led to the uncovering of the richly decorated walls and ceilings of the porticoes of the Rocchetta courtyard, which had been partially plastered over in the post war years. A Renaissance sgraffito decoration was revealed on the courtyard façades, at the centre of which is an S shaped motif surrounded by a circle of rays representing the sol invictus of the Visconti-Sforza families. They are also decorated with Greek, floral and geometric motifs painted with spontaneity. The architectural lines are accentuated by painted frames. These decorative musical scores are echoed on other ducal buildings as well as on the nearby complex of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

The works also brought to light decorations on parts of the vault carried out during Beltrami's restoration of the Castle in the 19th century. These were intended for the lapidarium, which was located here between 1899 and 1960 circa.

The cycle draws on the exploits of the Sforza family. The sol invictus, adopted from the family's heraldry was used to decorate the key stones. Faux late Renaissance architecture adorns the walls of the Rocchetta portico, most probably as the embellishment of an earlier entrance, as does an emblem that can be dated back to the Spanish occupation.

The restorations of 2012 had the purpose of bringing the Renaissance, Baroque and late 18th century decorations to light while maintaining, in part, the neutral layers of plaster applied in the post war years. These served the purpose of conserving the remaining fragments of decoration for future generations.

We left the courtyard and continued on to the northwest.

There is a large park to the northwest of the castle, the Parco Sempione. If we had more time, we’d possibly go walk through it.

We headed back to the castle.

This courtyard was opposite of the Rocchetta Courtyard that we just visited.

We walked by some pieces of some larger sculptures.

The main entrance to the castle is ahead of us below this tower to the southeast.

We looked around again before exiting.

There is a large fountain outside of the castle’s entrance.

Beyond the fountain, there is a large traffic circle with an equestrian statue of Giuseppe Garibaldi in the middle. This is the second large statue of him that we’ve seen. The first was on our first day in Rome atop the Janiculum.

There was some sort of gathering here. It wasn’t exactly a protest. They seemed to be roughly the Italian equivalent of the American PETA organization. They’re mostly out of frame on the right.

This tram stop featured an advertisement for Essence Birthday Bomb shiny lip gloss.

We walked around to the far side of the circle where we were able to see the Giuseppe Garibaldi with the front tower of the Castello Sforzesco in the background. And lots of wires for the trams.

We continued walking around the circle to exit on the north side to head to dinner nearby.

Dinner

We decided to eat at TheFisherMan, which was nearby. As the name suggests, their specialty is seafood. Specifically, with pasta.

We started off with some drinks.

Both seafood pasta dishes were interesting and very good! This small restaurant was different from most that we’ve been to in Italy in that you order at the counter but pay after eating.

And of course, we went to have gelato afterwards. We visited DASSIE, which was right by the nearby Lanza Metro station. We got mango, passion fruit, and white mint. All three flavors were good!

Milano Centrale

After dinner, we headed back to Milano Centrale from the Metro station.

It was pretty quiet when we returned to the station.

We briefly looked at the station’s exterior before returning to the Excelsior Hotel Gallia to end the day.