After breakfast at the Grande Bretagne, we walked over to take the funicular up to Lycabettus. We checked out the church at the peak and walked down, visiting another church on the way. We then took the Metro to Monastiraki, had lunch, and visited Hadrian’s Library and the Roman Agora on our way to Philopappou, which had a fantastic view of the Acropolis.

Morning

We woke up at the Grande Bretagne in time to arrive at the GB Roof Garden restaurant just after the 6:30am start time for breakfast. We had a beautiful view of the Acropolis and Parthenon from our seats by the open windows. Although the sun hadn’t risen yet, the sky was already starting to brighten.

We got a few items from the buffet, mostly the things that we liked from yesterday.

We ordered the smoked salmon from the menu, which came with some crustless toast.

We also ordered the fresh fruit, which was a little better than what was available at the buffet.

We thought we were trying some Greek yogurt. However, the text in red identifies this is Rice Pudding from Goat and Sheep Milk. Oops. It was… Interesting…

Unfortunately there were clouds in the sky and we didn’t get a nice glow on the Acropolis at sunrise. It’s still a beautiful view though!

We saw many tour buses down below in front of the Old Royal Palace.

Lycabettus

We headed out at around 9am to walk over to the funicular that goes up to the top of the Lycabettus, a tall hill to the northeast.

These ruins at the northeast corner of the intersection on the east side of the Grande Bretagne are “Part of the Athenian Fortification” according to a sign. No other details are provided on the sign.

After walking nine blocks or so, depending on exactly how you count, we reached some stairs.

The view looking back. Up until now, it had been a pretty gentle uphill slope.

After walking up the stairs, we were greeted with more stairs!

When we looked behind us after climbing these stairs, we were happy to see the Acropolis and Parthenon in the background! There was also a somewhat large group of tourists climbing up, the only real group of people we’ve seen so far this morning.

We walked a few more blocks to the northeast before reaching the road that the Lycabettus Funicular is on. This was the view to the southeast, in the opposite direction of the funicular station.

There were more steps to ascend.

The view looking back to the southeast at the top of the stairs.

We reached the funicular’s lower station at 9:35am. The funicular only runs every 30 minutes so we had a bit of a wait for the next trip up. We knew we would miss the 9:30am departure as there was no way we could arrive five minutes earlier.

There wasn’t anything to see on the ride up as the entire route is underground. At the top, our first view was to the southeast.

We walked through a small restaurant area after ascending up some stairs. We were able to see to the west from here. We stopped to apply some sunblock before continuing on.

We made our way to the overlook on the west side of the hill.

The church here at the east side of the overlook is the Church of Agios Georgios Lycabettus.

The church’s bell tower is near the western end of the overlook. The flag is flying at half mast due to today being Good Friday, the day that Jesus was crucified.

The overlook has a fantastic view of everything to the west due to the Lycabettus’ elevation being much higher than anything else in the area. From here, we could see just about everything that we’ve visited so far in Athens.

We took a quick look inside the church. It is almost the end of Lent as today is Good Friday and Easter Sunday is in two days. Easter is a major holiday here in Greece.

In the middle of this small church, a canopy, decorated with flowers, is placed over the epitaphios, which rests atop a bier. This bier is walked around the neighborhood in a procession at 9pm.

We started to begin the trip down via a path on the southwestern slope of the Lycabettus. This path has a number of switchbacks as it descends.

The view from below the overlook is actually a bit better as there is nothing obstructing the view.

We switched to the telephoto lens, first taking a look at the Acropolis and Parthenon. We could see that the area was devoid of tourists as the Acropolis doesn’t open until noon today due to Good Friday.

The Philopappos Monument, atop Philopappou, can be seen to the left of the Parthenon.

The spelling of Greek words in English is often inconsistent. We’ve tried to use the spellings that seem to be the most common. For example here, Philopappos and Philopappou both represent the same Greek name, Φιλοπάππου. We’ll use Philopappou to refer to the hill and Philopappos when talking about the monument atop the hill.

Looking to the left of the Acropolis, we could see the Temple of Olympian Zeus, which we visited two days ago.

And, further to the left, we could see the Panathenaic Stadium, which we also visited two days ago. It is open as we can see some people inside as well as many photographing it from outside.

Looking to the southwest, we could see the Hotel Grande Bretagne.

We could also see the Old Royal Palace.

The hill here in the background is the Pnyx, to the west of the Acropolis.

This is the west side of the Pnyx, The hill in front of it is the Areopagus.

The stairs that we had walked down after leaving the overlook at the top of the hill.

The path down was a bit steep but not hard to descend.

A wide angle view to the southwest as we were about to reach the end of the steepest portion of the Lycabettus.

The lower portions of the Lycabettus are not as steep and are lightly forested.

There is a restaurant, Prasini Tenta, here at this transition point. We did not eat there, though it does have a decent 4.5 rating on Google Maps. Instead, we walked to the northwest side of the restaurant to continue along a narrow road. This view was from a viewpoint just past the restaurant. We seem to still be at a slightly higher elevation than the top of the Acropolis.

We continued on the narrow road. It was lined with parked vehicles on both sides, leaving just enough room for one car to pass through at a time. This view is to the northwest.

We reached the Church of Saint Isidore. This church has a unique feature as it is built in a cave, or at least, part of it is within a cave. We went to take a look.

We walked up some stairs at the road leading up to the church.

We took a quick look around this first landing atop the stairs.

There was a small building here, a chapel? Interestingly, there is a tree that is growing through the side of the building!

We continued up one more level.

There was a small water feature here with a boat, koi, and even a turtle!

We continued up to reach the church. It wasn’t really possible to see anything as it was pretty crowded for such a small building.

We headed back down to continue our descent.

We ended up bypassing the lower funicular station as we descended. We ended up at the road that we had walked up earlier in the morning.

We wanted to take the Metro over to Monastiraki next. We decided to walk to the Evangelismos Metro station to the southeast as it is a little closer than the Syntagma Metro station, which is next to the Grande Bretagne.

We ended up walking through this small triangular plaza as we started walking to the southeast.

More stairs!

We came upon a farmers’ market on Xenokratous, a street that runs just a few blocks on the south side of the Lycabettus. This market is only here on Friday mornings so we were pretty lucky to come upon it!

We bought some delicious strawberries from one of the stands in the market. We then turned to head south to reach the Evangelismos Metro station. We actually briefly went into Evangelismos Park to take a quick look around. It didn’t seem particularly compelling as tourists so we headed down into the station.

There were some historic artifacts down in the Metro station. This is a terracotta pipe from the Pisistradid aqueduct and dates back to the 6th century BC!

This is part of a pottery kiln and is from sometime between the 1st century BC and 1st century AD.

This modern work of art is titled Mott Street and is by Chryssa, a Greek-American artist. Mott Street is basically the Main Street of Manhattan’s Chinatown.

The Metro station wasn’t too busy.

Monastiraki

We took Line 3 (Blue) to Monastiraki, just two stops away.

We decided to get lunch before continuing to sightsee. We passed by Monastiraki Square on its north side. The neighborhood of Monastiraki is named after this square which is named after a monastery that was located here. The monastery no longer exists but the Church of the Pantanassa, which was part of the monastery, is still here on the left. The road between us and the square was pretty busy so we didn’t try to cross here.

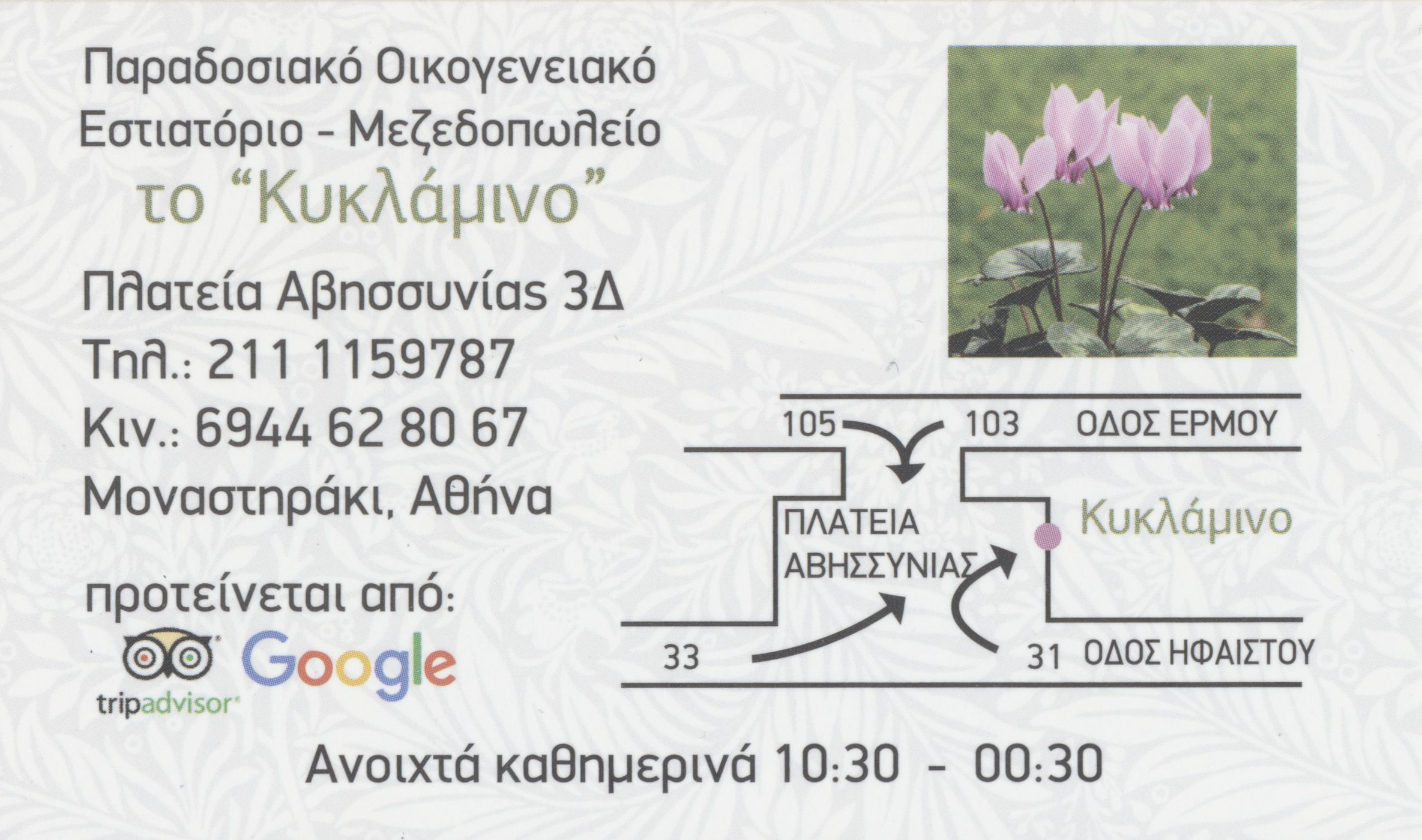

We ended up walking a few blocks to the west to The Kyklamino, a “Traditional Family Restaurant” according to their menu.

We ordered some juice…

And pork with wine sauce…

Lamb with oregano…

Meatballs…

And fried anchovies.

A free halva was provided for dessert, which seems pretty typical here. It was an excellent lunch!

The restaurant is on the east side of Avissinias Square.

We returned to Monastiraki Square after lunch.

The square has a view of the Acropolis, which is directly to the south. Only the very top of the Parthenon can be seen from this perspective as it is set back from the north side of the Acropolis.

Hadrian’s Library

We walked over to Hadrian’s Library to take a look. Admission is free today as it is the International Day For Monuments and Sites. Free admission days are great for visiting smaller sites like this one that are normally not as poplar as more well known locations. Generally, its a bad time to visit places like the Acropolis as they will be packed.

We did have to get free tickets from the ticket booth to the right of the entrance. As the name suggests, books, possibly in the form of papyrus, were kept here.

The first sign that we photographed was around here, in the middle of the site. There was a large church here, the Tetraconch Church, dating back to the 5th century AD.

The sign reads:

This is a monumental tetraconch church, which occupied the inner peristyled courtyard of Hadrian's Library. It was built according to one view by Herculius the Prefect of Illiricum (AD 407-412) or by the empress Eudocia, former Athenais, daughter of the sophist Leontius and wife of the emperor of Byzantium Theodosius B' (AD 425-430). The main church consists of a central hall, which ends on the east side at a semicircular apse. On the other three sides other semicircular apses are opened, each one of which has got four columns in semicircular disposition.

Some parts of a mosaic floor decorated with floral patterns are preserved. On the west side there was a narthex, which provided access to the main church through three gates. There is also a large atrium, which had galleries on three sides except that next to the narthex. The tetraconch was ruined towards the end of the 6th century AD. At the same site two churches were built successively, a three-aisled basilica in the 7th century AD and a domed church called Megali Panaghia in the end of 1lth - early 12th century AD, which was probably the first cathedral of the city of Athens. It was burnt and demolished in 1885, so that the first archaeological excavations could take place.

Part of the mosaic floor referenced on the sign for the Tetraconch Church might be here on the ground in front of us?

We continued walking to the east. Some of the ruins here were part of the Tetraconch Church. There is also a mosaic floor here which has some resemblance to the mosaic floor we just saw to the west.

The wall in the background is actually the side of the library’s main room.

A sign describes this large room:

THE MAIN EAST ROOM OF THE LIBRARY (BIBLIOSTASIO)

The main room of the Library, the one that Pausanias called 'oikimata', was at the eastern part of the peribolos. It had five large halls and four smaller of secondary use. The main hall, the bibliostasio, was rectangular in plan and its west side opened on to the inner peristyle of the monument through five large openings. It had a tall, continuous podium on the other three sides on which stood a colonnade of at least two storeys that supported a series of passageways. The walls on each storey had niches with wooden cupboards in which the books were kept. The total number of niches was 40, 16 niches on the eastern wall and 12 niches on the side walls. An estimate of the dimensions of the papyri gives an approximate number of 16.800 books. The wider, arched niches on the main axis of the eastern wall on both storeys probably housed statues of Athena and the deified emperor. The walls of the hall were decorated by marble revetments, while coloured marble slabs covered the floor.

The two halls at the left and right of the bibliostasio were probably subsidiary rooms (reading and transcription rooms), while the smaller rooms at the back served as staircases for the upper floor.

It seems like the columns were probably part of the library rather than the church?

This section of the library contained two auditoria.

A sign here describes these two auditoria:

AUDITORIA

The two corner halls of the eastern side of the monument were small, somewhat sloping auditoria, used for lectures and text' readings. They had marble seats and prohedriae (seats of honour) of a slightly curved form. The approach to the seats was by two staircases, along the long walls. The floor was made of marble, with diagonal quadrangular slabs of coloured luxurious marble, while marble revetments decorated the walls of the halls as well. The north auditorium is fully visible today, while most of the south auditorium is underneath the modern Adrianou street and the building at the corner of Aiolou and Adrianou streets.

We passed by some very neatly organized stone building parts!

We had a better look at the floor mosaics while walking by on the north side as we headed back to the entrance.

We walked down a short side path which didn’t actually lead anywhere. We did spot a black cat resting on a chair in the shade.

We passed by tons, likely literally, of building pieces!

We reached the wall of the large building to the left of the entrance. We weren’t able to get close to this building earlier as it can be only accessed when exiting.

There should be something under this metal roof. We weren’t able to access that area though so we don’t know what’s there. Maybe more carefully stacked building parts?

The large building on the right seems like it should be part of the library. There was another building here, the Church of Saint Asomatos, from the 12th to 19th century.

A sign here provides some details about this church:

THE CHURCH OF SAINT ASOMATOS "STA SKALIA"

Small church in the domed concised crosstype with the apse at the north side. It was built by the noble family Chalkokondyli at the 12th century and was renovated in 1576 by Michael Chalkokondylis. It was named Saint Asomatos because it was devoted to Archange! Michael by its synonymous founder, while because of its position at the Hadrian Library's propylon was named "sta Skalia" (on the stairs). At the beginning of the 18th century the narthex was fell into disuse and after 1843 the church was demolished. On the floor of the main temple, as well as in the narthex, were excavated eleven cist and vaulted graves, in which were buried mainly members of the Chalkokondyli family. The only visible remains of the church are the remains of a wall and the frescoe on the Library's façade, which represent "The Prayer in Gesthemane", "The Treachery of Judas" and busts of Saints.

An overview of Hadrian’s Library as seen through a fence after we exited and walked over to the southwest corner.

We continued on, walking one block to the south where we passed by some ruins. These ruins seem to be part of the Ancient Agora, which we’ll hopefully visit on another day.

The Roman Agora is on the other side of the street. We went in to visit, however, were instructed to go to the ticket office to pick up free tickets from there.

So, we walked over to the ticket office, which is in a building by the northwest corner of the site, and picked up our free tickets. We ended up resting on a bench behind the ticket office for awhile and also visited the bathroom.

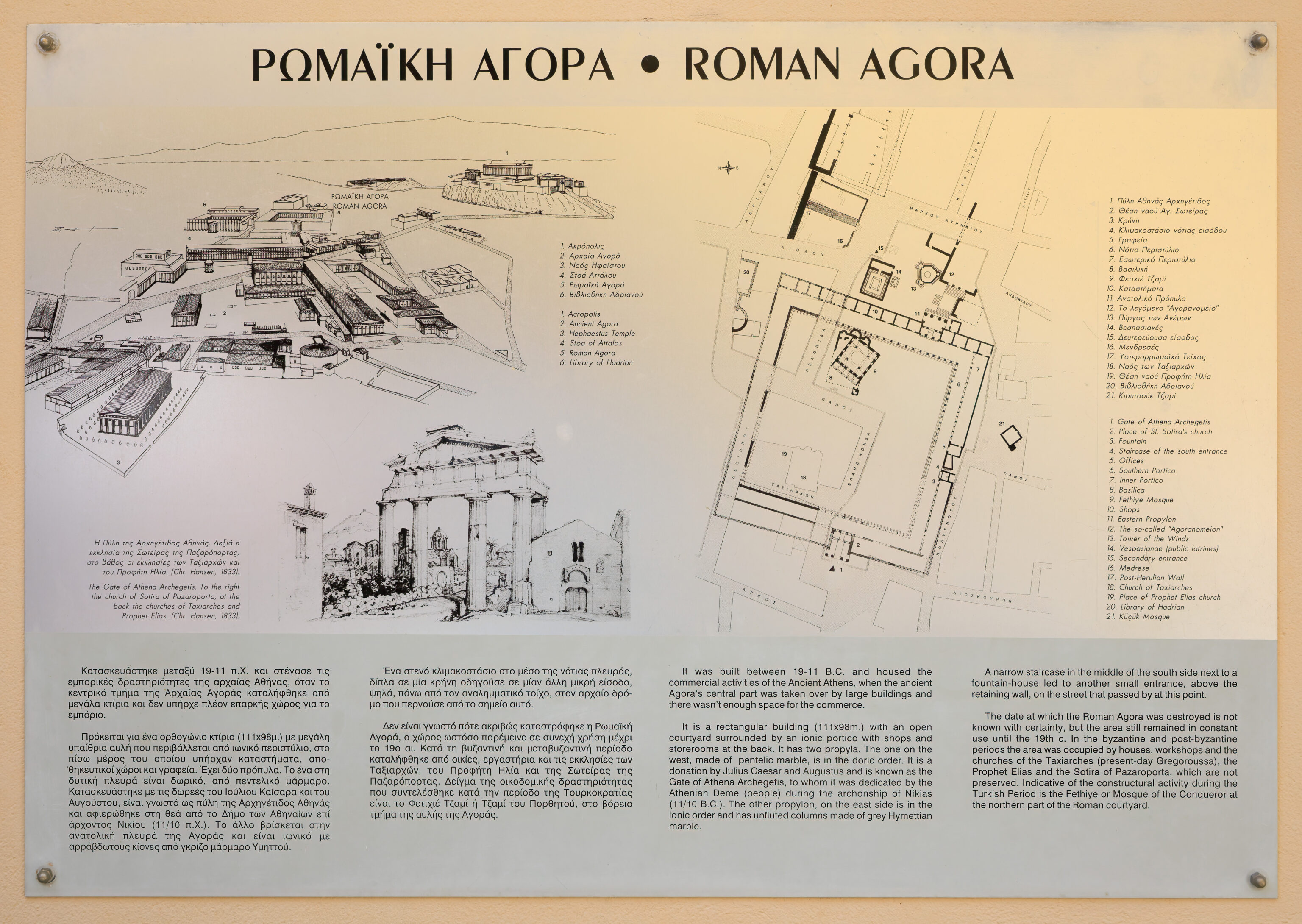

There was a pretty good map of the Roman Agora by the ticket office.

The English text on this sign reads:

ROMAN AGORA

It was built between 19-11 B.C. and housed the commercial activities of the Ancient Athens, when the ancient Agora's central part was taken over by large buildings and there wasn't enough space for the commerce.

It is a rectangular building (111×98m.) with an open courtyard surrounded by an ionic portico with shops and storerooms at the back. It has two propyla. The one on the west, made of pentelic marble, is in the doric order. It is a donation by Julius Caesar and Augustus and is known as the Gate of Athena Archegetis, to whom it was dedicated by the Athenian Deme (people) during the archonship of Nikias (11/10 B.C.). The other propylon, on the east side is in the ionic order and has unfluted columns made of grey Hymettian marble.

A narrow staircase in the middle of the south side next to a fountain-house led to another small entrance, above the retaining wall, on the street that passed by at this point.

The date at which the Roman Agora was destroyed is not known with certainty, but the area still remained in constant use until the 19th c. In the byzantine and post-byzantine periods the area was occupied by houses, workshops and the churches of the Taxiarches (present-day Gregoroussa), the Prophet Elias and the Sotira of Pazaroporta, which are not preserved. Indicative of the constructural activity during the Turkish Period is the Fethiye or Mosque of the Conqueror at the northern part of the Roman courtyard.

We returned to the site to enter with our tickets.

Our tickets were accepted, though it seems that the ticket office here now had additional free tickets to hand out. It seems they likely had just ran out when we arrived. After entering, we took a look at the Gate of Athena Archegetis from within the Roman Agora site.

Once again, they had lots of neatly stored building pieces!

The Roman Agora today appears mostly as an empty field with various columns and ruins on the sides. We actually encountered the same sign that we saw by the ticket office around here.

So neat and orderly! Much different from Rome!

We walked to the east end of the Roman Agora via its south side.

The building here on the right, of which only the facade survives, is of an unknown purpose. It is from the 1st century AD.

A sign briefly describes this ruin:

THE SO-CALLED "AGORANOMEION"

It is a public building the identification of which is not yet ascertained. It was built with porous ashlar masonry higher than the level of the east propylon of the Roman Agora.

A wide staircase leading to a façade with three archways and parts of the north and south walls are preserved.

According to the inscription on the epistyle of the façade the building was dedicated to Athena Archegetis and the divi Augusti (middle 1st c. A.D.).

The view looking back to the west.

This octagonal building is the Horologion of Andronikos of Kyrrhos. It dates back to the 2nd century BC and contained a water clock.

A sign describes this tower:

The Horologion of Andronikos of Kyrrhos

The Horologion of Andronikos, also known as the "Tower of the Winds" or "Aerides" (the blowing winds), a work by the architect and astronomer Andronikos of Kyrrhos in Macedonia, is located on the northern slope of the Acropolis, within short distance from the eastern propylon of the Roman Agora. It was built during the late Hellenistic period, possibly at the end of the 2nd century BC.

It is an octagonal edifice, 13.85 m. in total height, which incorporates a circular in plan space on the south side. The monument is made entirely of Pentelic marble with the exception of the foundations, which were built of poros, has two propyla and rests on a three-stepped base (crepidoma). The fully preserved roof of the building consists of twenty - four slabs and a circular "keystone" on which a Corinthian capital rests and possibly served as the base of a bronze wind vane in the form of a Triton. Inside the building a hydraulic mechanism operated, that powered a water clock or a 'planetarium' device of a manufacturing philosophy comparable to that of the Antikythera mechanism. It was powered by water pressure, which came from the interior of the cylindrical space situated on the south side of the monument. The incised lines on the exterior of the eight sides of the edifice corresponded to an equal number of sundials, whereas on the frieze above them, the personifications of the eight main winds are depicted in relief, bearing their symbols.

During the byzantine period, but also after the capture of the city by the Ottomans, the monument served as a church, as attested by the fragments of frescoes with christian content dated at the 13th-14th century, which still adorn the northern and northwestern side of the building's interior, and also by a documentary source that dates back to the end of the 15th century. In the late period of the Ottoman occupation, the building was also used as a tekke of the Mevlevi order. In later times, during 1838-1839 the Archaeological Society at Athens unearthed the entire monument, which was partly buried in the exterior and also to the level of the first cornice in the interior.

Another sign describes the modern conservation efforts undertaken to preserve this structure:

Horologion of Andronikos of Kyrrhos, the conservation of the monument

The 'Conservation and Valorization of the Horolcgion of Andronikos, at the Archaeological Site of the Roman Agora of Athens' was implemented based on the approved by the Directorate of Conservation of Ancient and Modern Monuments study, in the context of the National Strategic Reference Framework 2007 - 2013.

The surfaces of the monument were marked by a wide range of twenty-two different forms of deterioration. These were recorded as cracks, flaking, detached fragments, craquelure caused by the movement of blocks of marble due to external agents, heavy deposits of dirt, extensive biodeterioration, but also damage caused by man, in the course of the various functions the monument had.

The conservation of the monument encompassed a series of systematic interventions performed on the surfaces of the stone blocks, which completed the conservation and valorization of the monument: these included consolidation and cleaning of the surfaces, filling of cracks of different length and width, bonding of loose and detached fragments, removal and replacement of ineffective past interventions, investigation and conservation of the painted decoration and sealing protection of spots and openings against rainwater.

The 'healing' effect of conservation is evident and indeed astounding on the interior surface of the roof of the monument that was more severely damaged due to the ingress of rainwater. Persistent and arduous efforts revealed, conserved and maintained all traces of paint and coatings from the ancient polychromy up to the Ottoman inscriptions. The research methods applied brought to light new elements; a band of meander motif under the Ionic cornice and fragments of a byzantine fresco bearing the figure of an angel and a Saint on horseback that attest to the use of the building during the byzantine period are the most prominent finds.

Additional measures that concerned rainwater runoff were conducted on the outer surface of the roof of the monument. Water is channelled through the lion-head spouts away from the walls, in accordance with the initial estimate of the architect, further protecting the conservation interventions. The relief of the frieze bearing the eight sculpted figures of the winds was heavily damaged due to atmospheric pollution which is accountable for marble dissolution and the formation of thick black encrustations on its surface. The ancient surfaces were preserved, without performing any filling of the voids caused by the damages of the sculptural decoration or removing the black encrustations, so as to avoid losing valuable evidence that survived.

The entire conservation project - that was fully documented in deference to the principles of the international standards - handed over the now restored monument to the public and the future generations.

We took a quick look at the interior of the tower.

A sign outside describes the interior:

Horologion of Andronikos of Kyrrhos, the interior of the monument

The Horologion of Andronikos, a monument of the late Hellenistic period, that possibly dates back to the end of the 2nd century BC, is octagonal in plan and has two propyla as well as a circular in plan space on the south side, and it is made entirely of Pentelic marble with the exception of the foundations, which are built of poros.

Inside the monument, the holes that were used for mounting the hydraulic mechanism, which was installed in its interior and cuttings that were intended for water supply conduits, but also for fixing the marble parapet which isolated the mechanism, are still preserved on the floor's surface. The elevation of the masonry inside the monument is divided into four zones formed by three architectural elements that run the perimeter of the edifice: two lonic cornices, with the second one being more elaborately decorated, whereas the third zone takes the form of a stylobate that supports eight decorative colonettes, which prop up a two-banded epistyle. The traces of ancient wall painting, such as palmettes, lotus flowers and meander, which are still preserved in places are particularly significant. Blue paint covered the inner surface of the roof - one of the few roof structures of ancient Greek monuments that live on, which is comprised of twenty-four slabs and the circular 'keystone' that holds them together.

The fragments of the frescoes that survive on the northern and northwestern side of the edifice, which depict, an angel (possibly an Epitaphios lament scene) and a saint on horseback, are associated directly with the use of the Horologion of Andronikos as a church during the late byzantine period (13th-14th c.), if not earlier. In the late period of the Ottoman occupation, the building was also used as a tekke of the Mevlevi order, as denoted by the mihrab niche at its southeastern wall. Also inside the monument, the incised Roman ship (2nd - 4th c. AD), as well as the graphite drawings of sailboats that date from later times are notable.

The northeastern corner of the Roman Agora site, again with more stored stone pieces.

They already had public bathrooms in the 1st century AD!

A sign describes these “public latrines”:

PUBLIC LATRINES

It is a rectangular building with an oblong lobby and a rectangular hall, which has a bench with round holes around all four sides. It was roofed, except of an area above the centre of the great hall, which was open for the lighting and ventilation of the latrines. It worked in a very simple and practical system of running water, which flushed away the waste products through a deep peripheral canal to the main drain of the city (1st cent. A.D.).

It intended to serve the public that frequented the Roman Agora.

The Horologion as seen from the area around the latrines.

We returned to the entrance, walking along the north side of the Roman Agora this time.

A look back at the Roman Agora before leaving the site.

Philopappos Monument and Hill

We decided to head to the Philopappos Monument, atop the hill of the same name by the neighborhood of the same name.

We walked to the south towards the west side of the Acropolis, ascending up a bit of the side of the northern edge of the Acropolis. We then followed a path, which seems to be named Theorias, that went to the southwest. The view from this path overlooks the Ancient Agora.

The sign in the last photo reads:

THE AREA SOUTH OF THE ANCIENT AGORA

The "Eleusinion in the City", a shrine sacred to the mystery religion of the goddesses Demeter and Kore/Persephone, together with their mortal counterpart Triptolemos, dominates the north slope of the Acropolis, to the southeast of the Ancient Agora.

These Eleusinian deities were already worshipped here in the 6th cent. B.C., in an open-air shrine surrounded by a wall. In the 5th cent., a small rectangular lonic temple was built in the shrine. The following centuries auxiliary establishments, and dedications were added. The shrine was bordered by the Panathenaic Way on the west and the two branches of the «Street of the Tripods» on the north and south.

The Panathenaic Way extended from the Dipylon in the Kerameikos to the entrance to the Acropolis, cutting diagonally through the central square of the Agora. It was mainly of soil, but in the Ist or 2nd cent. A.D. the section in the northeast corner of the Agora and that along the west side of the Eleusinion was paved with stone.

On the west of the Acropolis is situated a rocky outcrop called the "Areopagus". The hill derives its name probably from Ares, the god of war, and the Ares-Erinyes or Semnes, underground goddesses of punishment and revenge. A judicial body, the Areopagus Council, met on this hill. The Areopagus was also a place of religious worship. Among the several sanctuaries located here was that of the Semnes or Eumenides.

In the Mycenaean and Geometric periods (1600-700 B.C.) the northern slope of the hill served as a cemetery, with both vaulted tombs and simple cist graves. From the 6th cent. B.C. onwards the hillside as a whole became a residential quarter belonging to the fashionable district of Melite. By the Late Roman period (4th-6th cent. A.D.) four luxury houses, which probably served as philosophical schools, had replaced the houses of the Classical era.

The Areopagus is also associated with the spread of Christianity into Greece. Some time near the middle of the Ist cent. A.D. the Apostle Paul is said to have converted a number of Athenians by teaching the tenets of the new religion from the summit of the hill. Among the converts was Dionysios the Areopagite, the patron saint of the city of Athens, who, according to tradition, was the city's first bishop.

Remains of the church of St. Dionysios the Areopagite closed into the north and west by the monumental Archbishop's Palace (16th-17th cent.) are preserved on the northern slope of the hill.

The path skirts around the northwest side of the Acropolis.

There was a huge queue at the main Acropolis entrance! It seemed to be advancing extremely slowly. We definitely would not want to have to stand out here on this queue under the hot afternoon sun!

We continued past the entrance. It was much calmer here.

The area to the southwest of the Acropolis is essentially a large public park. We found some benches to sit at by the Acropolis bus stop. There are city busses that stop here as well as all the tourist hop on hop off busses. There seemed to be two operators here, the Big Red Bus which is everywhere, and a blue colored bus which seems like it might be a local thing.

We sat for awhile before following a path into the park.

These caves are commonly referred to as the Prison of Socrates. Although Socrates was in fact put on trial and imprisoned, it was not here. This wasn’t even a prison!

A sign explains what these caves actually are:

PRISON OF SOCRATES

The cutting of groundwork and even of whole rooms into the rocky parts of the Hills west of the Acropolis (the Areopagus, the Hills of the Nymphs and of the Mouses, the Pnyx) is especially characteristic of the area, which serves as an open-air exhibition of the town-planning and architecture of the ancients, carved into rock. The impressive structure cut into the rocky slopes of the Hill of the Muses belong probably to a monumental two- or three-story dwelling, as we conclude from the alignments of beam-holes on the surface of the rock. The wooden beams supported the front part of the structure, which was made of stone masonry and wood. To the exterior floor belong passageways that connect with water-channels cut into the façade of the building, and a carved stairway at the south provided communication with the higher levels of the slope. The preserved back part of the structure is a complex of three rooms, carefully cut into bedrock, with doorways at the east and a cistern at the back. The use of the rooms is unknown. Its cave-like structure, however, and its proximity to the Athenian Agora must have led to the popular tradition that the building was the "Prison of Socrates" or an "ancient bath", as guidebooks and history books inform us. In the Second World War the structure was used to hide the antiquities of the Acropolis and the National Archaeological Museum and was sealed up with a thick concrete wall.

The Prison of Socrates is at the edge of a straight path. We followed that path to the northeast which took us to a much larger paved path. There was an unusual looking church on the other side of this larger paved path.

But first, we noticed these rough stone cubes. What are they?

A sign explains:

DIATEICHISMA

The "Diateichisma" was built by the Athenians at the end of the 4th century B.C. in order to confront the approaching danger from Macedonians. The new wall, which established a boundary on the crests of the Hill of the Mouses (Philopappos), the Pnyx, and the Hill of the Nymphs and at the north and south connected with the older Themistoklean Wall, reduced the extent of the fortified area of the city at the west, leaving unprotected large parts of the Demes of Melite and Koile. This middle wall, 900m. long, which was built according to the "emplekto" system (compartment wall), had two gates at its junctures with the Hills and was fortified with rectangular and circular towers. In the middle of the 3rd century B.C. the "Diateichisma" saw extensive repair in white poros-stone, the "emplekto" technique was abandoned, and its course in the area of the Pnyx was modified. In Justinian times, at 6th century A.D., the Diateichisma reinforced and kept in new repair and with added towers. Post-Byzantine manuscripts recall Justinianic activity here when they refer to the "Royal Wall".

The south gate of the Diateichisma, between the Hill of the Mouses and the Pnyx, at the axis of the most important commercial and traffic artery of Athens, the "Road through Koile", is identified, thanks to an ancient inscription, as the "Dipylon over the Gates". East of the gate is a small roadside shrine epigraphically recorded as dedicated to the homeric hero Aias or to Herakles, Athena and Demos, as protectors of the Gates. From byzantine era the militant Saint Demetrios Loumbardiares has been worshipped at the same spot. The north gate between the Pnyx and the Hill of the Nymphs has been identified as the "Meletides Gates" mentioned in the literary sources.

From the 4th century B.C. up to mediaeval times, the "Diateichisma", kept in repair, served as a first line of defence for the city of Athens from the west. Today the "Diateichisma" is preserved or can be traced along its whole length and gives important topographical evidence for the defence of Athens. Of the "Dipylon over the Gates" near the church of Saint Demetrios Loumbardiares, now partly covered with decor designed by the architect Pikiones, remains of only the south side of the tower are preserved.

This church is the Church of Agios Dimitrios Loumbardiaris, dedicated to Saint Demitrios.

A sign discusses this small Byzantine-era church and the landscaping around it:

SAINT DEMETRIUS LOUMBARDIARIS - LANDSCAPING OF DIMITRIS PIKIONIS

The church of St. Demetrius Loumbardiaris (The Cannoneer)

A small 12th c. Byzantine chapel of the vaulted single-aisle basilica type.

The chapel is built at the site of the north tower of the Diateichisma gate, called Dipylon above the Gates, and near a small temple-shaped structure, built in accordance with the ancient tradition of some divinity protecting the gates.

The construction of the chapel is probably associated with the final phase of the Diateichisma fortification wall (12th c. A.D.). Inside the church, frescos are preserved that date to 1732 according to the building inscription. The surname "Loumbardiaris" (the Cannoneer) is connected with the tradition that the church was saved by a miracle around 1640-1650, when the Turkish commander of the Acropolis, Yusuf, bombed the church from the Propylaea. The following day lightning struck the Propylaea, killing Yusuf and his entire family.

The church has undergone many changes over time. Its current form is owing to the restoration of its Post-Byzantine phase by the architect D. Pikionis in the 1960s.

The landscaping of Dimitris Pikionis

D. Pikionis (1887-1968) was an inspired architect, city planner, artist, scenographer and philosopher. He and his students executed the most important architectural landscape project in modern Athens between May 1954 and February 1958, The project involved the archaeological site around the Acropolis and Philopappos Hill.

The work included the creation of two spiral pedestrian walkways ending in two loops. The first approaches the archaeological site of the Acropolis and the other leads away from it towards Philopappos Hill, terminating at an open area called the Andiro (Belvedere), which overlooks the Acropolis.

The structure of Pikionis's pedestrian walkways, which utilize paving blocks, reused marble elements from neoclassical buildings, as well as byzantine and popular motifs, is original. The landscaping around the Acropolis was executed with absolute respect for the historical landscape and ancient topography. The work is organized into five main architectural "themes": the beginning and end of the ascent to the Acropolis, and the beginning, middle, and end of the walk on Philopappos Hill.

One of his particularly important architectural projects was the restoration of Saint Demetrius Loumbardiaris church, complete with open spaces and Kylikeion. In addition to his architectural creations, Pikionis stressed the appropriate planting of the area with small plants and bushes from Attica.

The treatment of stone-paved walkways, the road network, paths, and sidewalks around the two theatres (Herodus Atticus, Theatre of Dionysos) encompasses an area of about 80,000 m2.

Pikionis's internationaly recognised and award-winning project, in its time called "a creation of highly aesthetic character", was declared a protected historical monument and work of art by the Ministry of Culture in 1996.

We took a quick look inside. The interior was pretty plain.

We headed back out to continue up to the Philopappos Monument.

We walked up a rough stone path with stairs.

We started to be able to see the Parthenon atop the Acropolis through the foliage.

We came to a paved viewpoint where we could see most of the Acropolis! This perspective also allows us to see the rear of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus‘ stage building.

We continued on. We noticed that the stones on the ground also included decorative elements. We’re not sure what they are supposed to represent. This seems a bit like a delta in a square.

We continued to be able to see the Acropolis as we headed further up the hill.

Soon, we spotted the Triforce! We actually knew of its existence thanks to Google Maps. Someone had placed a Triforce Shaped Stone marker.

The Google Maps entry unfortunately was removed, however, there really is a Triforce shaped symbol on the ground! Like the other stone patterns on the ground, we’re not sure what it is actually intended to represent.

We continued ascending the hill.

We could see the Philopappos Monument ahead.

There was a sign here that describes the monument:

HILL OF THE MUSES - PHILOPAPPOS' MONUMENT

According to Pausanias, an ancient periegetic writer of the 2nd c. AD, the highest of the three Hills west of the Acropolis took its name from the poet Mousaios who lived, taught and was buried there.

The rock cut square to the northeast of the summit, which affords niches for statues, benches and alters for offerings, is claimed to belong to the funeral monument of Mousaios. It is more probable, however, that the Hill took its name from a sanctuary of the Muses to whom the Hill must have been dedicated.

The prevalent and commanding position of the Hill of the Muses, directly across the Acropolis, was the stronghold of the Athenians who, according to myth, fought against the Amazons. Throughout the ages it was used as a fortress of primary strategic significance during major military operations.

In the 5th c. BC the Athenians incorporated the Hill within the Themistoklean fortification, whereas the Diateichisma was constructed on its summit in the 4th c. BC. In 294 BC, Demetrius Poliorketes had a small fort built, known as the Macedonian fort, annexing the Diateichisma wall, where he installed a garrison to guard the city.

In the 2nd century AD a burial monument 12 m. in height was erected on the Hill of the Muses, which has since prevailed over the area. It takes its name from its founder Gaios Julius Philopappos, prince of Kommagene of Upper Syria and benefactor of Athens.

This monument is made of pentelic marble on a porous krepis. Its monumental curved façade facing the Acropolis is divided in two zones. The upper zone comprises three deep niches to support seated statues. In the central niche, Philopappos headless is depicted sitting on a throne with the inscription "Philopappos, son of Epiphanes, of the deme of Besa". In the left niche, according to the inscription "King Antiochos, son of King Antiochos", the fragmentary figure of Philopappos' grandfather is portrayed. According to the inscription which survived until the 15th c., the founder of the Seleucid dynasty "King Seleucus, son of Antiochos, Nikator" was depicted in the right niche. The lower zone is a relief freeze depicting Philopappos on a quadriga flanked by licktors. The burial chamber in the form of a naiskos which housed the Philopappos' sarcophagus was behind the monument.

The monument survived intact until the 15th c. but gradually fell victim to vandalism and the elements. It was partly restored by the civil engineer N. Balanos in 1904.

The area by the sign has a pretty good view of the Acropolis.

The hill continues to the southwest. We didn’t go in that direction though.

The partially ruined monument is surrounded by a fence.

A sign here describes both this hill and this monument:

THE HILL OF THE MUSES (PHILOPAPPOS)

According to the ancient traveller Pausanias, the highest of the three Hills west of the Acropolis took its name from the poet Mousaios, who lived, taught and was buried on it. The flat surface chiselled into bedrock northeast of the crest of the Hill, with niches at the west that allow for statue-bases, benches and a table for offerings, has been thought to belong to the funeral monument of Mousaios. Likelier, however, is the identification of the area as a shrine of the Muses, to whom the hill must have been sacred.

The towering and commanding position of the Hill over against the Acropolis served, in the age of myth, as a stronghold of the Athenians against the Amazons and was later used as a strategically significant fortification in important military operations. The Athenians of the 5th century B.C. included the Hill in the Themistoklean defence works, and in the 4th century they set up, as a boundary, the "Diateichisma" at its crest. In 294 B.C. Demetrios Poliorketes incorporated into the old walls a small fortress, known as the Macedonian Fortress and installed a garrison to control the city.

In the 2nd century A.D. Gaius Julius Antiochus Philopappus, prince of Kommagene in Upper Syria and benefactor of Athens, erected on the top of the Hill of the Muses his grave monument, 12m. high, which from then on dominated the area and gave his name to the Hill.

The monument, built of pentelic marble over a porous-stone base, is divided into two zones. The lower has a frieze showing Philopappos in a chariot with a retinue of rod-bearers and the upper has niches, of which the middle shows an enthroned Philopappos, with the inscripion "ΦΙΛΟΠΑΠΠΟΣ ΕΠΙΦΑΝΟΥΣ ΒΗΣΑΙΕΥΣ" ("Philopappos of Besa, son of Epiphanes") and the second, according to the inscription, "ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΣ ΑΝΤΙΟΧΟΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ANTIOXOY" ("King Antiochos, son of King Antiochos"). In the right niche, no longer, was depicted the founder of the dynasty, "ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΣ ΑΝΤΙΟΧΟΣ ΣΕΛΕΥΚΟΣ ΝΙΚΑΤΩΡ” ("King Antiochos Seleukos Nikator").

The monument, intact up to the 15th century, has gradually fallen victim to vandalism and natural phenomena. It was partly restored in 1904 by K. Balanos.

From the monument, looking east and a little bit to the north, we could see the very eastern edge of the Acropolis as well as the Acropolis Museum. The Old Royal Palace can be seen as well on the left, although it is a bit hard to identify unless you know what you’re looking for. The top of the Lycabettus can also be seen, with part of the hill blocked by trees.

Looking to the south, nothing really stands out to us. It’s just lots of buildings all the way to the Mediterranean.

From the east side of the monument, looking to the northeast, we have a partial view of the Acropolis with the Parthenon in sight as well as the Lycabettus in the background.

This view, nearly identical to one we took on our way up, is a pretty good perspective.

We switched to our telephoto lens to take a closer look at the Parthenon and Lycabettus. It was about 5:20pm when we took this photograph. The Acropolis is closed and free of visitors. We can see people up on Lycabettus though. The funicular operates until after midnight on normal days and there doesn’t seem to be anything that limits access to the hill during other hours.

We also took a look at the Propylaia, the entrance structure on the west side of the Acropolis.

We walked down the path just a little bit to have a more complete view of the Acropolis. This includes just about everything there is to see!

A closer view from the same position.

We continued on our descent, with the view starting to be blocked by foliage.

The view along the path on the way down.

We ended up turning right at a junction and headed down the east slope of the hill rather than continue to the northwest where we came from. The nearest Metro station Sygrou–Fix, is closer this way. Although, in reality the Acropoli station is probably also the same distance away.

The path that we are on ends here with stairs that descend to street level below.

We continued southwest past the first street we encountered. This narrow path descends between residential buildings.

This neighborhood is Koukaki, on the south side of Philopappou.

We decided to visit Dolce Far Niente, a tiny ice cream shop that was nearby, just one block off the most direct path to the Metro station. The name of this shop is in French, meaning literally Sweet Doing Nothing. We are familiar with the phrase Far Niente as it was the name of one of the restaurants at the St. Regis Bora Bora. We visited Bora Bora in 2019 and stayed at the St. Regis. It is still the best hotel experience we’ve had globally!

As for the ice cream, it was good! We also got these little dessert balls as sort of a topping.

The road turned into a pedestrian street with shopping and restaurants on either side. It was still probably a bit early for it to be truly lively.

Syntagma

We took the Metro from two stops from Sygrou–Fix to Syntagma.

There is a big decorative clock above the middle of the station’s fare gates below.

There are some ruins behind a glass barrier in the station.

We exited the station at Syntagma Square.

It was about 6:50pm, ten minutes before the 7pm guard change. So, we went to watch it again. This time, we stood on the right side knowing that the left side wouldn’t be ideal due to where the officers have stood so far. We also noticed that the guard uniforms have changed.

We were finally able to record the entire guard change!

Greek flags in front of the Old Royal Palace as we headed across the street.

There was a bit of color in the sky as sunset approached.

We noticed that we could see the top of the Lycabettus from the street.

We walked back over to the Grande Bretagne.

A view of some windows on the interior of the hotel by the elevators on the way back our room.

One Reply to “From Lycabettus to Philopappou in Athens”