After breakfast at the W, we started the day at the Colosseum. After visiting the arena and walking around the amphitheater, we spent the rest of the day at the adjacent Palatine Hill and Roman Forum. We left at closing time and had dinner nearby. We briefly viewed the Colosseum at night before returning to the W.

Morning

After waking up at the W Rome, we headed downstairs for breakfast at the restaurant. We ordered the cream cheese, salmon, and avocado bagel as well as an omelette with everything but mushrooms.

One of the wait staff offered some pastries that were a bit different from the ones from the buffet. This one is an apple Danish.

We also ordered the fried rice just to see what Italians come up with when they make fried rice. This is one of three items that doesn’t count against the one per guest entree selection. It’s definitely skippable.

The waiter that took our order also offered bacon, which we of course accepted. Bacon isn’t actually on the menu and is not available on the buffet. It was somewhat nicely cooked though all clumped together.

Of course, we also got some things from the buffet. Unfortunately the fruit here is a bit mediocre.

Colosseo

The Colosseo (Colosseum), formally the Anfiteatro Flavio (Flavian Amphitheatre), is probably Rome’s #1 tourist destination. There are four areas of the Colosseum that can be visited – the attic, underground, arena, and general admission. Timed entry tickets are released one month in advance and are extremely hard to get for the attic and underground areas. Its reported that it sells out within minutes. We were able to get arena tickets without much trouble, though they do sell out. The general admission tickets do seem to sell out as well.

While we could have walked to the Colosseum from the W, we decided to take the bus instead. Most of the various bus options take about 30 minutes, possibly with a transfer. It is also possible to take the Metro which is potentially faster.

We arrived at the Colosseum at 8:35am, 25 minutes before our 9am entry time. The bus that we took stops right in front it.

We found the queue for ticket holders, which was advancing slowly. There are multiple ticket checks as well as airport style security.

After passing through security, everyone is funneled into a passageway on the outer edge of the Colosseum.

There are signs for the four different ticket types as they all have separate entrances. We headed to the arena. After another ticket check, we found ourselves in a passageway facing the middle of the Colosseum.

As we entered, we could see a blocked off walkway to the side.

We walked out onto the arena floor, or at least, a small reconstructed portion of it. We walked forward as far as we could. From here, we could see the underground section of the Colosseum below us.

Obviously, much has been lost here at the Colosseum but many walls still remain.

We came across one of our favorite European signs!

Looking back, we could see some of the interior structure of the Colosseum but with quite a bit missing, particularly the flooring where the seats would have been.

There’s just a simple wood and wire fence at the edge of the arena floor.

While the arena floor, located on the eastern end of the Colosseum, wasn’t huge, it was more than big enough for all the visitors who had tickets.

We spent some time enjoying the view of this nearly 2,000 year old amphitheater! It is huge and impressive!

We headed back to the interior portion of the Colosseum to enter the general admission area as all tickets include it.

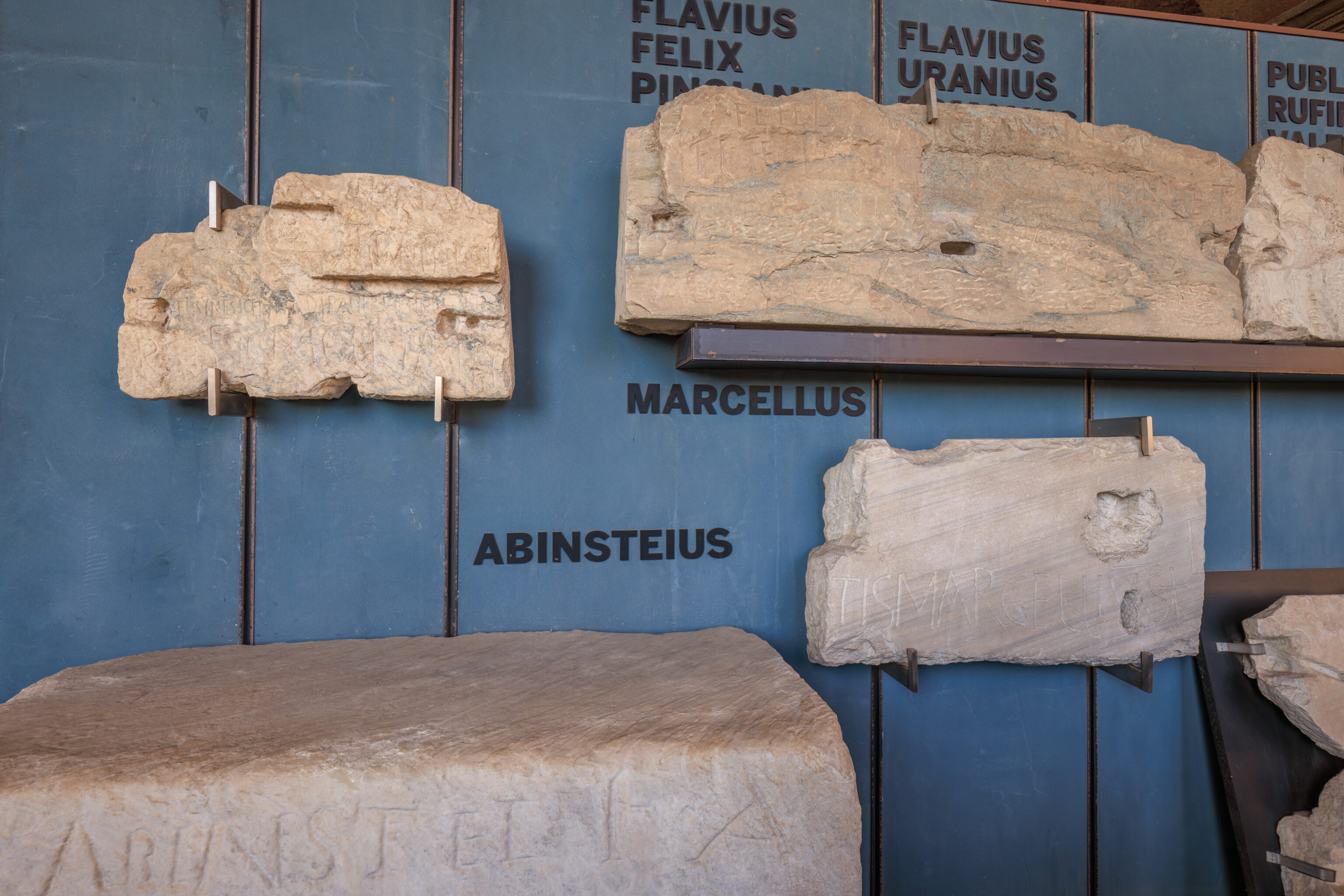

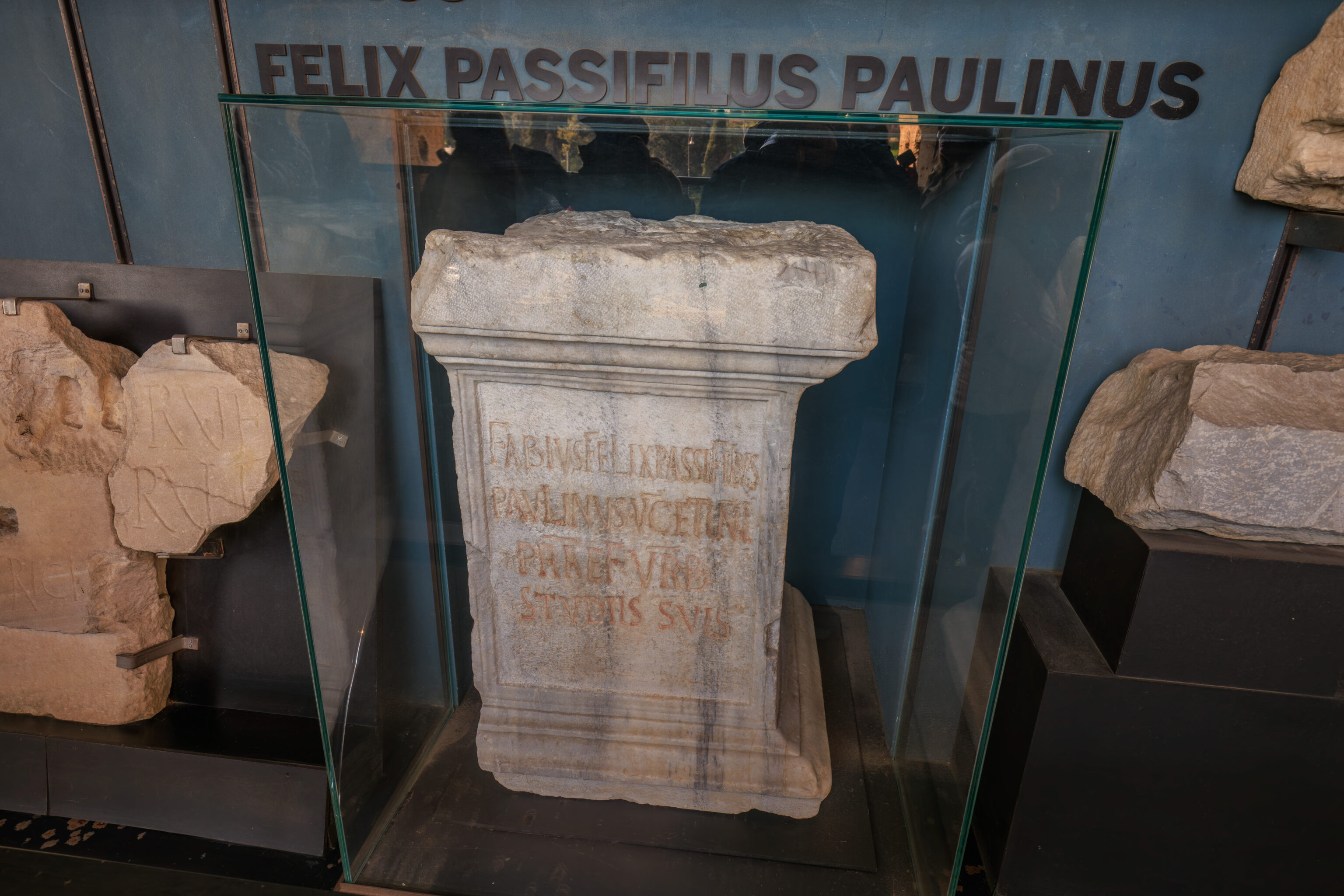

We entered a museum area which has various artifacts from the Colosseum as well as informational panels. This area was fairly large and long as it was around the edge of the building. It was quite busy here.

We ended up outside on the second floor of the Colosseum, well above the arena level. It was pretty crowded here!

This second floor level is a mostly narrow path that runs all the way around the interior of the Colosseum. Although it was crowded, we were still able to easily get a spot at the edge to look inwards. This elevated area, compared to the arena, is set back a good amount from where the arena floor would be if it was complete.

We don’t actually know what areas above are accessible with attic tickets.

While it was super busy where we were now, the arena floor where we were earlier was still pretty sparse overall. It looks like the attic is over on the right as we see railings and people above. It seems unlikely there is access to the upper portions of the Colosseum anywhere else as the remaining outer wall isn’t as high.

Left, center, and right from above the arena entrance.

And, a panorama generated from the previous trio of photos.

Parts of the route provide access to the outer wall, like here with a view to the east.

We continued walking clockwise around the Colosseum.

We had a nice view to the south from around the southernmost point of the Colosseum.

This triumphal arch, which is being restored, is the Arco di Costantino (Arch of Constantine). It was created in honor of Emperor Constantine‘s victory in a series of civil wars.

We continued on, getting closer to the western end of the Colosseum.

Here, we were above where we joined the queue earlier after arriving at the Colosseum. The Arch of Constantine can be seen along with the Palatino (Palatine, also referred to as the Palatine Hill) beyond.

The route ends here, above the western end of the Colosseum and directly across from the entrance to the arena on the eastern side. We visited the gift shop which is between this area and the outer wall of the Colosseum before heading back downstairs.

We bought a small model of the Colosseum. It was surprisingly made in Italy!

Back on the ground floor, we looked across to the east side of the Colosseum.

Looking to the left, we could see where we started walking around the Colosseum on the floor above, more or less above the large cross at ground level. It does look like there is a viewing area near the cross which we missed.

We started walking counter-clockwise, which was the only way to go.

Looking above and to the left, we could see the western end of the Colosseum where the route above ended.

The highest remaining wall of the Colosseum was directly across from us to the north.

This passageway led to another gift shop, which we did not visit as we had already visited the one on the 2nd floor.

Continuing on, we were directly across from the large cross on the other side of the Colosseum. The attic section above is more obvious from this perspective.

This was as far as we could go, more or less at the southernmost part of the Colosseum. They are building a replica ramp over on the right which is supposed to be based on the design which allowed animals to be brought up from below.

This view, to the northwest, shows the western edge of taller section of wall that remains.

We exited the Colosseum from here.

The southwestern edge of the Colosseum, as seen from the exit path which goes to the west.

We ended up where we started, at the western end of the Colosseum.

Palatino and the Foro Romano

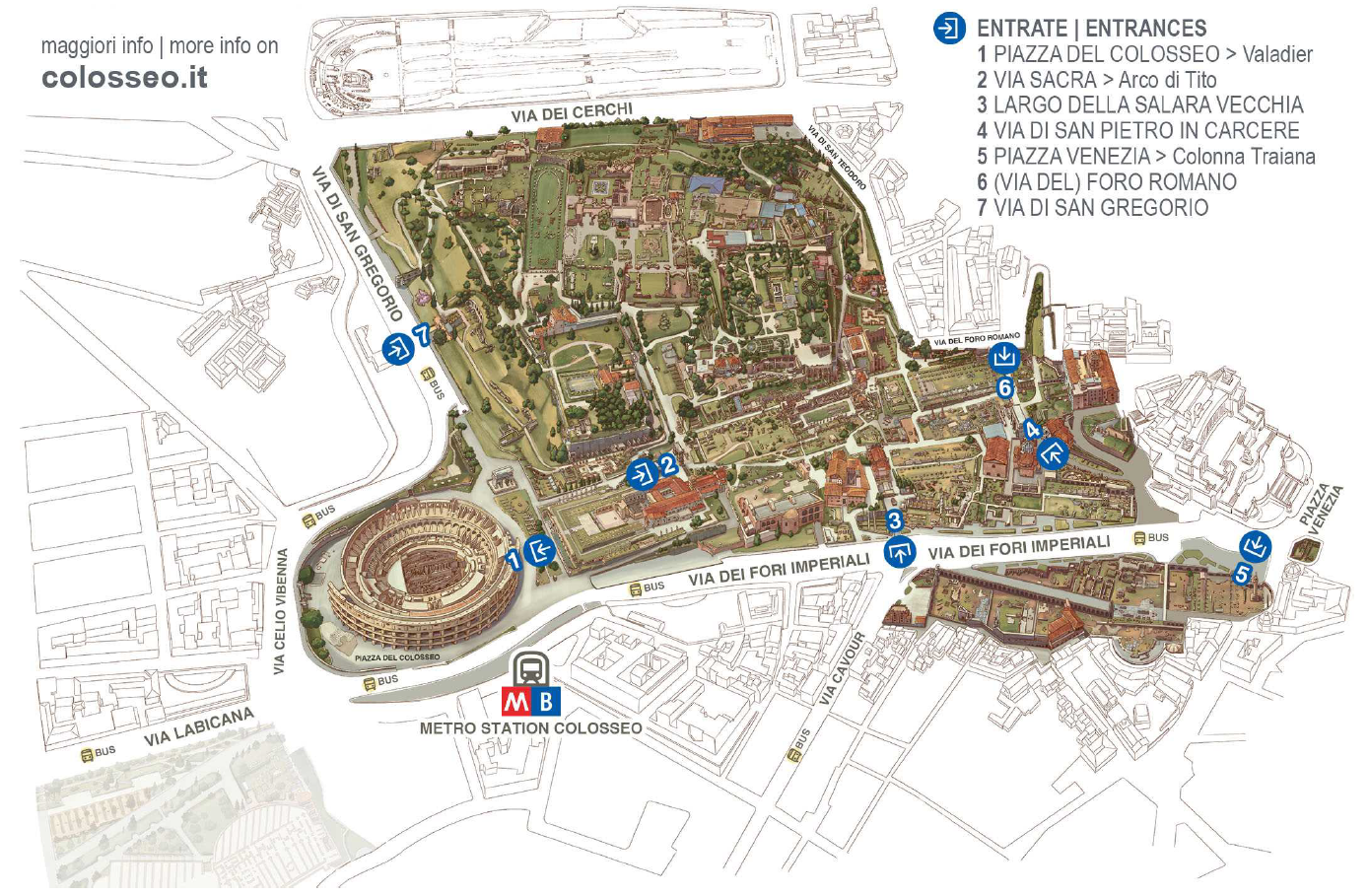

Entry to the Colosseum includes access to the Palatine and Foro Romano (Roman Forum). This is one huge area to the west of the Colosseum. For the attic, underground, and arena tickets, the Palatine and Roman Forum can be visited either the day before, on the same day, or the next day, though only one entry is allowed. The general admission ticket seems to allow access within a 24-hour period either before or after the scheduled Colosseum entry time based on the Italian description of the ticket. The English description seems to be phrased incorrectly.

There are multiple places where it is possible to enter the Palatine and Roman Forum. We decided to use the closest entrance, which is nearby. We walked past the Arch of Constantine on our way there.

One neat feature of modern Rome is all the SPQR stuff everywhere. SPQR stands for Senatus Populusque Romanus, meaning the Senate and People of Rome, and is a phrase that represented the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire after it. SPQR can be seen all over Europe at historical sites dating back to Roman times when nearly all of Europe was part of the Roman Empire.

The Colosseum as seen from around the path that leads up to the Palatine.

Don’t feed the cats!

We followed this path up the Palatine. We saw a queue on the right, which turned out to be the entrance queue. It wasn’t entirely obvious as others kept on going to the end of the path. We went to the end as well and verified that this was the queue we wanted to join. Once again, there was a ticket checker as well as security to enter.

After entering, we looked to the east to see a bit of the north wall of the Colosseum as well as a line of columns.

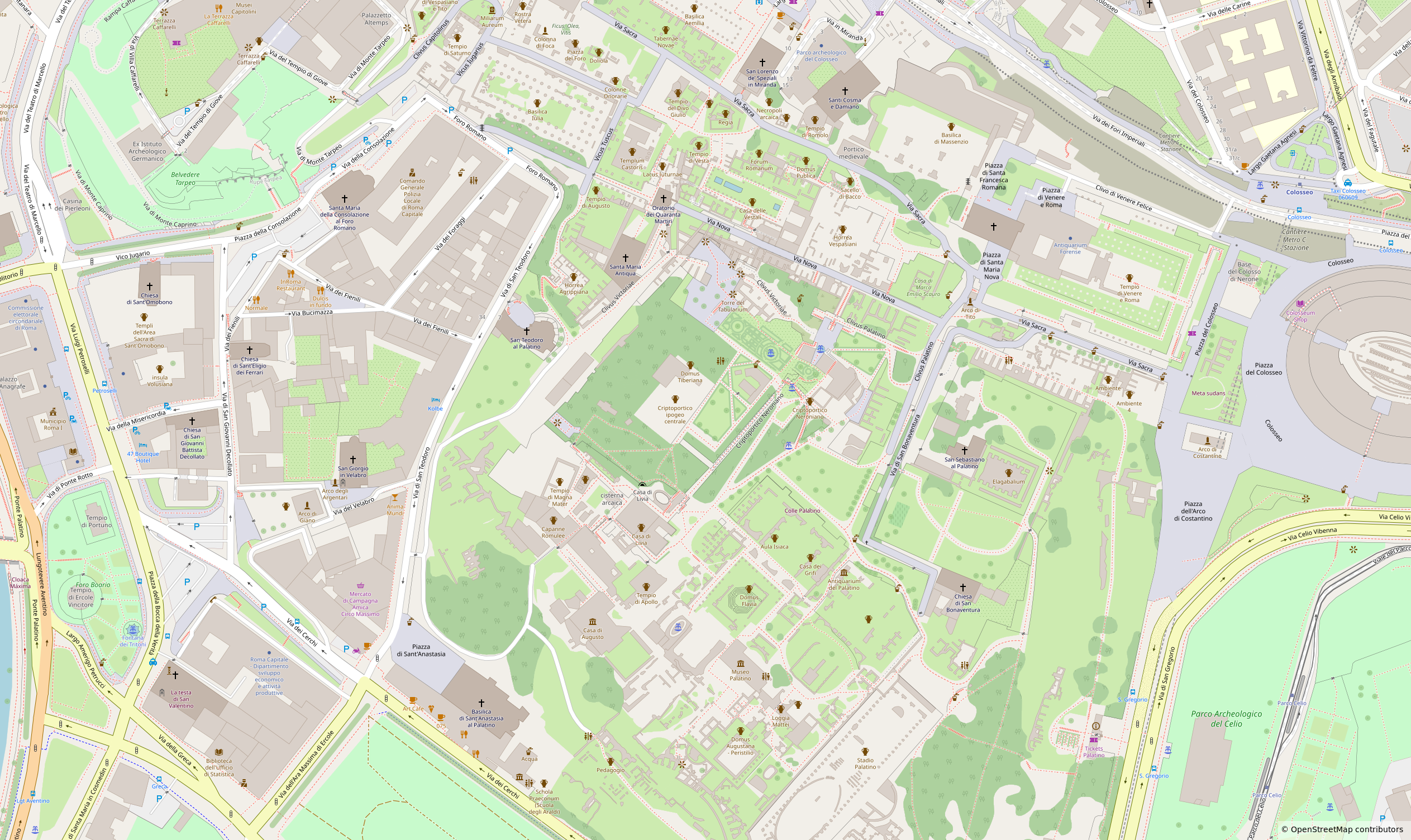

Unfortunately, while we did see others who seemed to have maps, we never got one. OpenStreetMap has the best map for the Palatine and Roman Forum.

The ticket PDF also had a map, though its primary purpose was to indicate the nearest Metro station and all the various entrances.

This arch is the Arco di Tito (Arch of Titus). The path that we took to enter the Palatine would have passed under this arch if it wasn’t for the entry gate being off to the north side of the path.

From near the arch, looking to the west, we could see the Roman Forum below on the right. The Palatine, which is the name of a hill, is up on the left and extends from the west to the south. There seems to be a pretty good viewpoint up on the Palatine directly in front of us.

There is a church here, the Santa Francesca Romana al Palatino, with a tall bell tower. It is connected to some other buildings which are part of the historical site here.

We decided to start at the northeastern corner of the Palatine, the portion closest to the Colosseum, primarily because it is just a small section of this huge area.

Walking to the east, we could see this large structure on our left which was attached to the back of the Santa Francesca Romana al Palatino A sign explained that this is the Tempio di Venere e Roma (Temple of Venus and Rome):

TEMPLE OF VENUS AND ROMA

The Temple of Venus and Roma was built on the Velian Hill by the emperor Hadrian (AD 117-138). It has two cellas, located back-to-back. The temple was later restored by the emperor Maxentius (AD 308-312) after a fire. In the Hadrianic phase, the temple was constructed of blocks of peperino stone faced with marble, and the cellas were divided by a flat wall. In the Maxentian period, the cellas were lined with brick, and apses and coffered concrete vaults were added. These can be seen today. The cellas were set within a double colonnade, the remains of which can be seen only at ground level today. The long sides of the temple platform were lined with porticoes of grey granite columns. In the 9th century the western part of the temple was taken over by the Church and Convent of S. Maria Nova, today known as S. Francesca Romana.

The path we took was parallel to the path which led us up to the entrance of the Palatine.

Upon reaching the eastern end of the Palatine, we were directly across from the Colosseum.

We walked to the west to get a closer look at the Temple of Venus and Rome.

We looked back to see the Colosseum again from a slightly more elevated position.

This was once the section of the temple dedicated to Venus, as explained briefly by a sign:

CELLA DEDICATED TO VENUS

The largest temple ever seen in the city of Rome was dedicated by Hadrian to the joint cult of Venus and Roma. Here Venus was honoured in particular as the mother of Aeneas, the founder of the city. The only remains of her cult statue that survive are a fragment, in porphyry, of the drapery of her clothing. The statue must have depicted the goddess standing, with a Cupid in her right hand and a spear in her left.

We’re not sure if these are the fragments referenced by the sign?

The path led us to the other side of the temple, dedicated to Rome.

We continued on into the Nuevo Museo del Foro Romano, (New Museum of the Roman Forum) which sits between the Temple of Venus and Rome and the Santa Francesca Romana al Palatino. We walked quickly though the museum as even though it was only 11am in the morning, we wanted to have time to see all of the Palatine and Roman Forum.

This building does contain bathrooms. It is a good idea to visit them as it turns out bathrooms are pretty scarce here!

There was also a projection screen with a short film about the temple here.

We headed back out, returning to where we started within the Palatine as the museum’s front entrance was near the Arch of Titus.

We could see the top of the Monumento a Vittorio Emanuele II (Monument to Victor Emmanuel II) from here. The monument is just northwest of the Roman Forum.

We decided to continue on by going south, further onto the Palatine. We passed by a book shop on our right as we ascended further up the hill.

We turned left at the first opportunity, walking through what seems to be a small tunnel or underpass and ending up in a grassy walled off area with a small vineyard.

A building was to the north on the far side of a large tree. The tree was an olive tree. A sign explained the significance of olive trees to this region:

THE OLIVE, TREE OF HEALTH AND PROSPERITY

The Palatine Hill, heart and soul of the Roman Empire, offers itself as the ideal location to tell the story of the olive tree and to promote the properties of extra virgin olive oil (EVOO), a foodstuff at the very core. of the Mediterranean diet and, from our very beginnings, one of the Romans' main sources of prosperity. The Parco archeologico del Colosseo has teamed up with Coldiretti Lazio and Unaprol to promote a project to raise awareness of EVOO culture through an educational itinerary that teaches visitors all about the characteristics of the olive tree and olive oil, as well as the central role that this ancient plant played in ancient culture.

This building is a chuch:

CHURCH OF SAN SEBASTIANO

The Church of S. Sebastian lies close to the remains of the monumental entrance to the Vigna (Pentapylum?), and in part is built over the paving of the temple. The 'Acts of the Martyr Saint Sebastian' relate that the Saint, brought before Diocletian, addressed him standing “super gradus Heliocabuli" ('on the staircase of Elagabalus'). Recorded in documents since the 10th century, the church preserves from that period only the important painted decoration of the apse. The rest was destroyed during its rebuilding by Pope Urban VIII Barberini in 1624.

Another sign, to the east of the church building, explains what was here:

TEMPLE OF ELAGABALUS

The construction of this monumental temple complex took place in two distinct phases, between AD 190 and AD 240. Entry to the complex was from the west, by a stairway and multi-arched entrance (Pentapylum?). The temple lay at the centre, but only its foundations remain. The area was enclosed on its sides by porticoes and the open area was occupied by broad garden areas. The temple was probably dedicated to Sol by the emperor Elagabalus (AD 218-222), and later to Jupiter Ultor by Alexander Severus (AD 222-235).

To the south, there was a larger building attached to the wall.

Walking east to the edge of the Palatine, we could see the Colosseum, now to our northeast.

We continued via a small path that went through the eastern wall around this area. We followed the path south, going past the large building that we saw from within the walled off area.

We ended up on what is probably best described as a grassy hillside with a sparse canopy of trees above.

We continued past some ruins.

And ended up on the northern end of the “Stadium”. A sign explains:

THE PALATINE "STADIUM"

This area provides a view from above of the "Stadium", an important sector of the Flavian Palace which is never given this name in the ancient sources. In fact it was a garden, more specifically a hippodromus, the word with which it was described by late authors. In Rome hippodromes, originally areas where horses were exercised, came to be elongated rectangular spaces with paths and flowerbeds. Deriving from the Greek gymnasiums, these were luxurious garden areas present in important villas. The Palatine "Stadium" (160 x 48 m) had a rounded south end and was surrounded by a portico supported by marble-clad engaged columns. The central part consisted of a broad curved avenue for strolling on foot, on a litter or even in a carriage, a custom described by Martial and Juvenal, authors of the Domitianic period (AD 81-96). On the eastern side is a large exedra from which to enjoy views over the garden below, luxuriously decorated with sculptures and two semi-circular fountains at either end.

The ruin on the left is the Domus Severiana and included a bath complex.

A sign here facing north, away from the Stadium, seems to describe this general area:

NYMPHAEUM AND ADJOINING CISTERNS

The short northern side of the "Stadium” – above some service rooms ended in a square room with niches decorated with statues and fountains fed by a complex system of water pipes. Some large cisterns in the underground area to the rear, already known in the Renaissance and drawn by Pirro Ligorio, ensured a water supply to the Flavian palace. A branch of the Claudian aqueduct (Aqua Claudia) which ran from the Caelian Hill to this part of the Palatine supplied the cisterns, where the water decanted before being distributed.

This seems like it might describe this area of ruins in front of the building in the background, which is the same building that we saw from the other side earlier. That building is the Chiesa San Bonaventura al Palatino. Looking on Google Maps, it seems this church is accessible without entering this ticketed area of the Palatine via a path which bypasses the area around the Arch of Titus and goes above the underpass that we walked through earlier.

Looking to the west from here, we could see more ruins.

The path here continues around the west side of the Stadium with more buildings beyond as well as a large one under renovation. The large building is the Museo Palatino (Palatine Museum).

But, we decided to backtrack as we wanted to walk around from the east side of the Stadium to the south to see some of the buildings there. The path also seems like it should descend below this level, giving a view of the south edge of the Palatine from a lower elevation. That south side seems to be lined with the ruins of a long wall with many arches.

We rejoined the path that we were on earlier which went through a grassy hillside and continued walking south.

Up ahead, we could see ruins of Domus Severiana on the right and the arched wall ahead. This arched structure is referred to as the Arcate Severiane (Severian Arches). It seems this structure was created to provide a platform above, basically an extension of the Palatine.

This path, to the northeast, bypasses the area of the Palatine that we walked through. It seems it skirts around the edge of the hill and ends up back at the Arch of Titus. There may also be an entrance and exit beyond the arched structure, which is a small section of the Aqua Claudia, a 43 mile long aqueduct.

We continued walking to the south. Unfortunately, we could not go much further as the path was blocked off here. It did look like the area beyond was configured for visitor access as we could see an informational sign on the right, however, it was closed.

This perspective shows these structures from the east, again, blocked off by fencing but otherwise in a state that seems like it is setup for visitors.

So, we backtracked and returned to the west side of the Stadium to continue walking atop the Palatine.

This was the view from here to the north.

The remains of a room, part of the Domus Augustana, can be seen just to the west of the edge of the Stadium. As the name suggests, this would have been the Emperor’s residence.

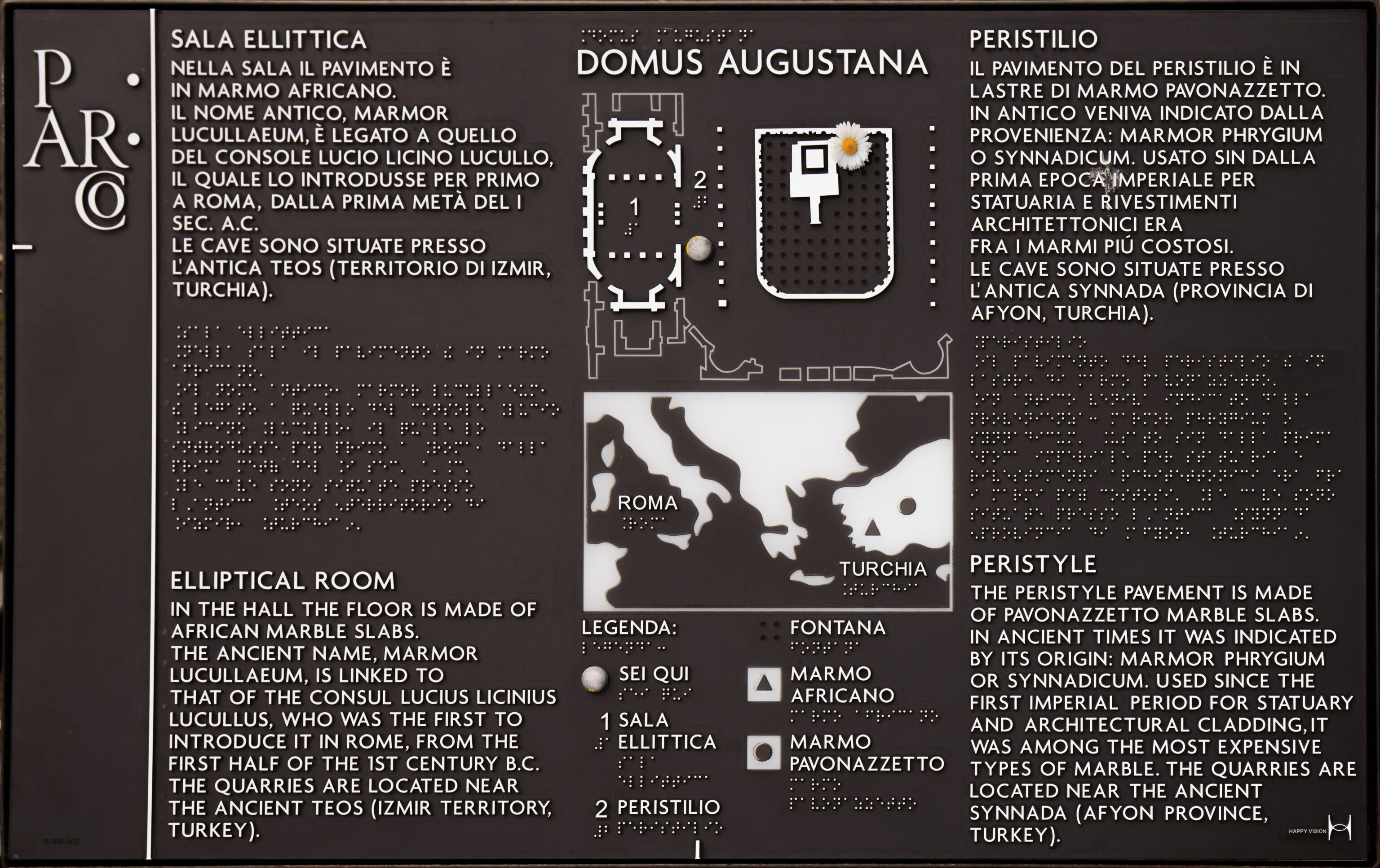

This sign explains the room and the flooring.

ELLIPTICAL ROOM

IN THE HALL THE FLOOR IS MADE OF AFRICAN MARBLE SLABS.

THE ANCIENT NAME, MARMOR LUCULLAEUM, IS LINKED TO THAT OF THE CONSUL LUCIUS LICINIUS LUCULLUS, WHO WAS THE FIRST TO INTRODUCE IT IN ROME, FROM THE FIRST HALF OF THE 1ST CENTURY B.C. THE QUARRIES ARE LOCATED NEAR THE ANCIENT TEOS (IZMIR TERRITORY, TURKEY).

PERISTYLE

THE PERISTYLE PAVEMENT IS MADE OF PAVONAZZETTO MARBLE SLABS. IN ANCIENT TIMES IT WAS INDICATED BY ITS ORIGIN: MARMOR PHRYGIUM OR SYNNADICUM. USED SINCE THE FIRST IMPERIAL PERIOD FOR STATUARY AND ARCHITECTURAL CLADDING, IT WAS AMONG THE MOST EXPENSIVE TYPES OF MARBLE. THE QUARRIES ARE LOCATED NEAR THE ANCIENT SYNNADA (AFYON PROVINCE, TURKEY).

A sign here discusses olive trees:

MINERVA'S OLIVE TREE

Classical sources consider the olive tree sacred to Minerva, as the goddess bestowed it upon humankind when she struck a rock with her spear and caused the first olive tree to spring from the ground. Olive oil became one of the Romans' greatest treasures, used to light up the night, treat wounds and offer sustenance to the populace; olive branches honored illustrious citizens and victors. The olive trees present on the Domus Augustana, the great imperial palace built under Domitian on the Palatine Hill atop previous constructions, commemorate the emperor Domitian's devotion to Minerva. Domitian dedicated numerous temples and homages to the goddess, as we can see by the great number of coins minted during his reign that bear her likeness.

This sign is possibly here due to the trees on the small hill to the left which seem to be olive trees?

It’s a bit hard to imagine what was once here as now it is basically a grassy field with mostly ruined wall sections here and there. A small sign tries to explain what was here in the Upper Peristyle:

DOMUS AUGUSTANA

UPPER PERISTYLE

The ground floor of the "private" sector of the palace was arranged around a porticoed courtyard with coloured marble columns, identical to that in the public sector; at the centre was a large pool within which a small temple was built at a late-period, accessed from a small bridge on arches. At the sides of the peristyle were various living and banqueting rooms, some of which still bear traces of their fine coloured marble floors. On the walls of one of these rooms the remains of frescoes on Christian themes (now severely damaged) were found, belonging to a late oratory

The only obvious thing here is the small bridge on arches.

We continued walking southwest along the northwestern edge of the Stadium.

This was as far as we could walk in this direction. From here, we continued on to the right.

We walked through a section of ruins of the Domus Augustana.

We came across this area, described as the Lower Peristyle by a sign:

THE LOWER PERISTYLE OF THE DOMUS AUGUSTANA

The lower peristyle, visible from above, was lavishly decorated and had at its centre, as usual, a grand fountain. Its most distinctive feature was its pattern of four peltae (crescent-shaped shields, as used by Amazons) separated by semi-circular channels.

THE ORIGINAL HEIGHT of the shields and of the fountain at the centre is uncertain, but it was probably several metres. We should probably reconstruct it with a very high jet of water at the centre. The area was also decorated with abundant flower beds, small basins perhaps for ornamental fish, and a lavish sculptural programme. This distinctive stage set-like arrangement of water and architecture was surely inspired by some of the structures of Hadrian's Villa.

The open area was surrounded by numerous living rooms and nymphaea, which would have made it a particularly cool part of the palace on hot days.

One of Rome’s ever present gulls posed for us here.

We went through this passageway to the northeast. There were a few remnants of decorations on the wall.

We ended up just west of where we were earlier, at the southwest end of the Upper Peristyle.

This alcove in the wall is a bit reminiscent of the Temple of Venus and Rome.

We came across a collection of column parts on the ground.

We returned to the area above the Lower Peristyle. There wasn’t any obvious way to get down there and although there was a sign at the opposite corner, we didn’t see any people at the lower level.

As we continued on the route, looking down, we saw crates filled with stone ruin pieces.

We ended up at the northwest side of the Lower Peristyle.

There was a grassy field to the west filled with yellow wildflowers, with more ruins beyond. There was also a more recent building which stood by itself.

The path ends here to the southwest of the Lower Peristyle. A sign describes the rooms that were here as part of the Domus Augustana.

ROOMS OF THE DOMUS AUGUSTANA OVERLOOKING THE CIRCUS MAXIMUS

In this sector of the palace are some of the rooms overlooking the porticoed courtyard on the underground level 10 metres below, which hosted private apartments still accessed today by an ancient staircase. There are also the remains of a suite of rooms arranged symmetrically and with the typical recesses fotriclinia (couches) Each room opened onto a semi-circular courtyard, adorned with a fountain and communicated through doors with the porticoed panoramic terrace, which closed the façade of the palace on the side facing the valley of the Circus Maximus.

The Circus Maximus referenced on the sign occupies the entire area to the southwest below the Palatine. Although it is visible from here, it is mostly obscured by trees. Historically, it was used for chariot racing.

We backtracked a bit and walked by the west side of the Museo Palatino (Palatine Museum), which is being renovated. This put us just west of the Upper Peristyle in a place referred to as the Domus Transitoria, as explained by a sign:

THE TRANSITIONAL HOUSE

Beneath the Triclinium of the Flavian palace lie important remains of Nero's palace which, according to ancient authors, extended from the Palatine to the Oppian hill. Nero's grandiose domus, initially named "transitoria", was rebuilt after the fire of AD 64 and renamed "aurea" ("golden"). The Neronian rooms were excavated by the Farnese family in the 18th century and again in the early 20th century. Two ancient staircases lead down to a courtyard which has a nymphaeum divided into niches on one side; the central niche hosted a cascade which fed the water jets in front of a platform adorned with little coloured marble columns. On the opposite side was a colonnaded pavilion used as a summer living room by the emperor, who reclined in the semicircular niche. At the sides of the courtyard were luxuriously decorated rooms with colourful inlaid floors, marble walls and frescoes depicting epic scenes: the paintings, embellished with glass inserts, mainly illustrated the Trojan war cycle, a favourite subject for Nero (the paintings are on display in the Palatine Museum). At intervals along the walls were stepped structures for cascades of water. The profusion of gilding in the painted decorations was intended to create an immediate link with the Golden Age, of which Nero saw himself as the initiator.

We could see some remnants of the flooring described on the sign. The building in the background is the same one we just saw earlier from when we were by the Lower Peristyle.

To the north, there is what was once a courtyard with an octagonal feature in the middle. Remnants of marble flooring are still present in what has become a grassy field.

This seems like a decorated piece of wall?

We saw this long segment of wall from afar earlier when we were on its southeast side. Now, we are on the opposite side. This wall belongs to what is referred to as the Casa dei Grifi (House of the Griffins):

HOUSE OF THE GRIFFINS

A steep staircase, part of which is ancient, leads from the back of the so-called Lararium to the underground floor of a house dating to the 2nd-1st century BC. Though partly destroyed by the foundations of the palace above, it gives some idea of the type of aristocratic residence which stood on the Palatine in the Republican period. The house had two storeys: on the ground floor a few remains of the atrium with its pool in peperino and coloured mosaics survive; the underground level is preserved almost intact and its rooms are adorned with frescoes, mosaics and stucco decorations. One of these, depicting two griffins, gives the building its name.

From near the House of the Griffins, looking to the northeast, we could see the bell tower of the Santa Francesca Romana al Palatino, the church near where we entered the Palatine.

This field in front of us seems like it is the Audience Chamber of the Domus Flavia:

DOMUS FLAVIA. SO-CALLED. AUDIENCE CHAMBER

The largest room, probably reserved for audiences with the emperor, is traditionally known as the Audience Chamber. It was of exceptional size (1280 sq m.) and had a complex architectural decoration of which many features survive. Eight niches for colossal statues opened into the walls: two were recovered intact in 1724, a Hercules and a Bacchus in green basalt, whilst only the head of a Jupiter was found. The niches were inside bays and framed by a colonnade several storeys high, with finely carved bases and capitals and a frieze with military motifs.

The Domus Flavia seems to be more or less the same area previously described as the Domus Transitoria.

After walking around a bit and ending up on the western side of the courtyard with octagonal feature in the middle, we came across a sign that describes the Domus Flavia a bit:

The Domus Flavia was the public part of the great palace built by Domitian, occupying the central and southern area of the Palatine Hill.

We are in the central peristyle of the palace, overlooked by the main reception rooms: on the northern side are the remains of the so-called Aula Regia, and Lararium, while to the south was the 'Cenato Iovis', a large heated triclinium that still preserves remains of the splendid opus sectile decoration.

The large peristyle, which housed an octagonal fountain, consisted in two rows of columns in coloured marble - portasanta and pavonazzetto - embellished by composite capitals.

We ended up here on the west side of what was referred to as the Domus Transitoria.

There are inaccessible below grade areas here.

This was as far as we could go, more or less in front of this building that we saw earlier. This building is described as the Farnese Lodge and dates back to the 16h century, as explained by a sign:

FARNESE LODGE

A small two-storey building known as the Casiro del Belvedere stands on the remains of one of the nymphaeums at the sides of the large triclinium belonging to the imperial palace of the Domitianic period (AD 81-96). Dating to the 16th century, it was rebuilt by the Farnese family who added a two-order loggia covered with frescoes and a travertine balustrade. The paintings, which still survive, depict bucolic landscapes on the walls and grotesques on the vaults, adorned with ovals dedicated to deities such as Venus or mythical figures like Hercules, Cacus or the Argonauts.

The oval shaped depression in the ground is described as a Nymphaeum by a well faded sign, roughly translated from Italian to English using Google Translate as the English section of the sign was no longer legible:

DOMUS FLAVIA. ELLIPTIC NYMPHAEUM

On the sides of the triclinium and in communication with it were two symmetrical porticoed courtyards, characterized by a curved side. One of the two lies today under the Palatine Museum, while of the other, better preserved, there remain the foundations of the colonnade, some fragments of the yellow marble columns and a good part of the external wall in which there are doors and niches for statues. The center of the courtyard was occupied by an elliptical fountain, all covered in white marble, with several basins placed at three levels of height and filled in a cascade of water.

An even more faded sign discusses the inlaid marble floor in front of us here. It is still readable upon very close examination:

INLAID MARBLE FLOOR

The magnificent inlaid marble floor with its elegant geometrical and floral design was excavated in the time of the early 20th century together with the rooms beneath attributed to Nero's Domus Transitoria, to which it is usually thought to belong. In fact the floor has a different orientation from Nero's buildings but similar to that of the nearby Augustan complex, making its attribution uncertain. The floor belonged to a hall with internal porticoes supported by columns, of which the foundations in travertine blocks survive.

There were a few options as to where to go next. We decided to go to the northwest.

We walked by a building with some rooms that we could sort of look into, along with some stone pieces sitting on a retaining wall. This building, with a modern protective roof above it, seems to be the House of Livia, as described by a sign on its northwest side:

HOUSE OF LIVIA

One of the best-preserved late Republican houses on the Palatine is that known as the "House of Livia" due to the discovery in its cellars of a water conduit with the name of Augustus' wife Livia stamped on it; she must therefore have lived here. Among the surviving rooms, on the basement storey, are a sort of atrium supported by travertine pillars with four large rooms opening onto it adorned with mosaic floors and efined II style wall paintings. On the walls are scenes drawn from myth and genre paintings. In the central room (the so-called tablinum) are Mercury freeing lo, loved by Jupiter, from imprisonment by Argus, and the nymph Galatea fleeing the enamoured Polyphemus. In the left-hand mom (the so-called wing) are winged griffins and other fantastic creatures whilst the right-hand room has a painted portico decorated with a yellow frieze with fantasy landscapes from which hang festoons of leaves, flowers and fruit. The side room (the so-called triclinium) is painted with illusionistic architectures opening onto rural sanctuaries dedicated to Apollo and Diana. The sunken atrium gave access via an internal staircase to the upper storey of the house where small service rooms survive, probably including a kitchen with a plain tiled floor (opus spicatum) and typical facilities like a well, a counter and a basin. The house, built in around the early 1st century BC was altered several times shortly afterwards; some of these alterations can perhaps be attributed to Livia and thus to Augustus himself.

We didn’t see any way to enter the house or get a better look at whatever is inside. Another sign describes this general area:

AUGUSTAN SANCTUARY AND RESIDENTIAL COMPLEX

On the summit of the Palatine facing the valley of the Circus Maximus and near the mementos of the founder Romulus kept in the sanctuary of Victoria and Magna Mater, excavations have brought to light the remains of the house of Augustus and the large sanctuary he dedicated to Apollo in 28 BC. The area previously hosted a late Republican residential district (2nd-1st century BC). This was an area of aristocratic houses, with luxurious wall and floor decorations, of which significant remains survive to give us an idea of how the Palatine looked when it was home to Rome's most powerful men. According to ancient authors, Octavian initially lived in one of these houses, chosen for its vicinity to the original home of the founder Romulus with whom the prince wished to identify himself. Later on, starting from this house, Augustus began the construction of a sanctuary dominated by the temple of Apollo, his tutelary deity, which also incorporated his new private residence alongside the state residence to which he was entitled as High Priest. Also belonging to the sanctuary were a shrine of Vesta, a broad portico in front of the temple of Apollo decorated with statues, and a library opening onto the portico used occasionally for Senate meetings. The large complex commissioned by Augustus completely changed the area's appearance, transforming it into a series of sacred buildings linked to the memory of Rome's first emperor.

This appears to be a cistern, as explained by a sign:

ARCHAIC CISTERNS

Two circular cisterns dating to the 6th century BC can be seen in the area of the sanctuary of Victoria and Magna Mater, cut into the tufa and made of blocks of the same material with an internal coating of plaster. One had an ogival roof while the other was uncovered and accessible via a staircase. Built to store water, these cisterns soon became dumps for votive materials. The numerous pottery fragments collected inside indicate the existence of a cult dedicated to a goddess practiced here even before the construction of the two temples of Victoria and Magna Mater (3rd century BC)

These alcoves may have been guard rooms, as explained by a sign:

SERVICE ROOMS NEXT TO THE PLATFORM

The platform of the Domus Tiberiana, clearly visible here on the south side, was crossed by galleries connecting the various sectors of the palace and linking parts of the Palatine which would otherwise have been separate. The emperor Caligula was assassinated in one of these tunnels in AD 41. The platform also hosted service rooms. The numerous vaulted chambers built up against the platform on this side may have housed the palace guards, as suggested by the graffiti with drawings and names of soldiers scratched into the plaster.

These days, they seem to store stone pieces.

There is what seems like an active archeological site here along with some other ruins, some of which are protected with roofs. Nearby, a sign explains that this area is the oldest part of Rome, where the Casa Romuli (Hut of Romulus) was located around the 8th century BC.

THE HUT OF ROMULUS

IN THIS AREA STOOD THE ANCIENT DWELLING-PLACE OF THE FIRST KING OF THE CITY, AND THE MOST ANCIENT RITES WERE PERFORMED, TRACES OF THE VILLAGE BUILT ON THE PALATINE HILL ARE IN THE POST HOLES AND FOUNDATIONS OF THE HUTS, MADE OF INTERTWINED BRANCHES. THE HUTS WERE BOTH THE DWELLING PLACE OF THE KING, THE HIGHEST PRIEST, AND THE PLACE OF WORSHIP OF MATRIARCHAL FEMALE DEITIES.

TEMPLE OF VICTORY

THE SACREDNESS OF THIS PLACE IS CONFIRMED BY THE DEDICATION OF A TEMPLE FOLLOWING VICTORY OVER THE SAMNITES IN THE BATTLE OF SENTINO OF 295 BC.

SANCTUARY OF THE MAGNA MATER

DEDICATED TO CYBELE, THE GREAT MOTHER OF THE GODS, THE TEMPLE WAS LOCATED ABOVE A LARGE SQUARE LINED WITH SHOPS, LAUNDRIES, A SMALL ROMAN BATHS BUILDING AND LATHRINES FOR THE PILGRIMS.

The story of Romulus and Remus, his twin brother, is that they were abandoned by the Tiber rather than be killed by the King. They were raised by wolves and then by Faustulus, a local shepherd. After they grew up, they wanted to found a new city but disagreed about where to build it. Romulus wanted to build it on the Palatine but Remus wanted to build on another hill, the Aventine. Ultimately Romulus killed Remus and then founded Rome here.

A sign here seems to indicate that part of this area that is being worked on is a village of huts:

HUT VILLAGE

On the summit of the Palatine facing the Tiber, excavations have brought to light a small hut village, usually linked to the foundation of Rome. Their existence is indicated by trenches and holes dug into the soil, from whose form archaeologists have deduced the presence of two huts with beaten earth walls, supported by a framework of wooden poles and with a roof of interwoven branches. The position of the huts, coinciding with that described by ancient authors, has suggested that this was the place where the founder Romulus traditionally lived.

The next area that we entered was identified on a sign as the Casa di Augusto (House of Augustus). It requires one of four ticket types to enter: Full Experience, Only Arena, Forum Pass Super, or Membership Card. The Colosseum arena ticket is a Full Experience ticket so we were able to show our tickets to enter. A sign explains what we are about to walk through:

THE PRIVATE APARTMENT

The House of Augustus, completely reopened to visitors for the Bimillennium celebrations after long and painstaking conservation work, lay west of the Temple of Apollo, the focal point of the whole Augustan complex. It consisted of two adjacent sectors that shared an entrance but were distinct from one another: 1. the private apartment; 2. the official sector. The low two-storey private apartment, closer to the entrance and the Romulean Huts, was more intimate and modest. The floors were in black and white mosaic and the ceilings plain; the rooms of various sizes were connected by a single central corridor. Those to the left of the corridor, thanks to their position near the entrance, remained in use during the imperial period when they underwent some profound changes. The rooms to the right, including two bedrooms, abandoned and buried after Augustus, are better preserved. In the "Room of the Pine Festoons", the painted decoration consisted of garlands on a background of illusionistic architecture with porticoes; the segmental vault of the ceiling was covered in white stucco and there was a black and white mosaic on the floor. More remarkable from the point of view of the painted decorations was the nearby "Room of the Masks", most of whose wall paintings survive. These consist of a series of masks against an architectural background; this motif is clearly theatrical in nature, deriving from late Hellenistic drama. This room also had a simple mosaic floor and a flat white stucco ceiling.

An adjacent sign describes the Public Sector of the residence:

THE PUBLIC SECTOR

East of the private apartment, at a slightly lower level (about 20 cm), were a series of grander rooms, facing onto the peristyle and with more refined decorations: inlaid marble floors, whose imprints are clearly visible, and high vaulted ceilings with stucco decorations of which large fragments survive. Clearly, this part of the house was reserved for public functions; at the centre was the Oecus (the main hall), larger than the other rooms and flanked by symmetrically arranged chambers: two long narrow rooms, perhaps passageways; two rooms with niches, probably private libraries; another two rooms with antechambers. The rooms at the back were service or storerooms.

The central Oecus, now profoundly altered, was the main room, as indicated by its larger size and peculiar architecture: the brick podium running around the walls and accessed by two steps suggests that it was a small triclinium (dining room). The best preserved painted decorations are to be found in the "Room of the Perspectival Wall Paintings", where the back wall develops the themes of the Second Pompeian Style: standing on a podium is a tall two-storey structure that occupies the central wall in an elaborate play of perspective ending in a small shrine. In the background is more illusionistic architecture and some still lives.

This first room of the Private Apartment, right by the entrance, cannot be entered. However, it has what seems like a plastered wall.

A long corridor with wooden walkway lead further into the structure.

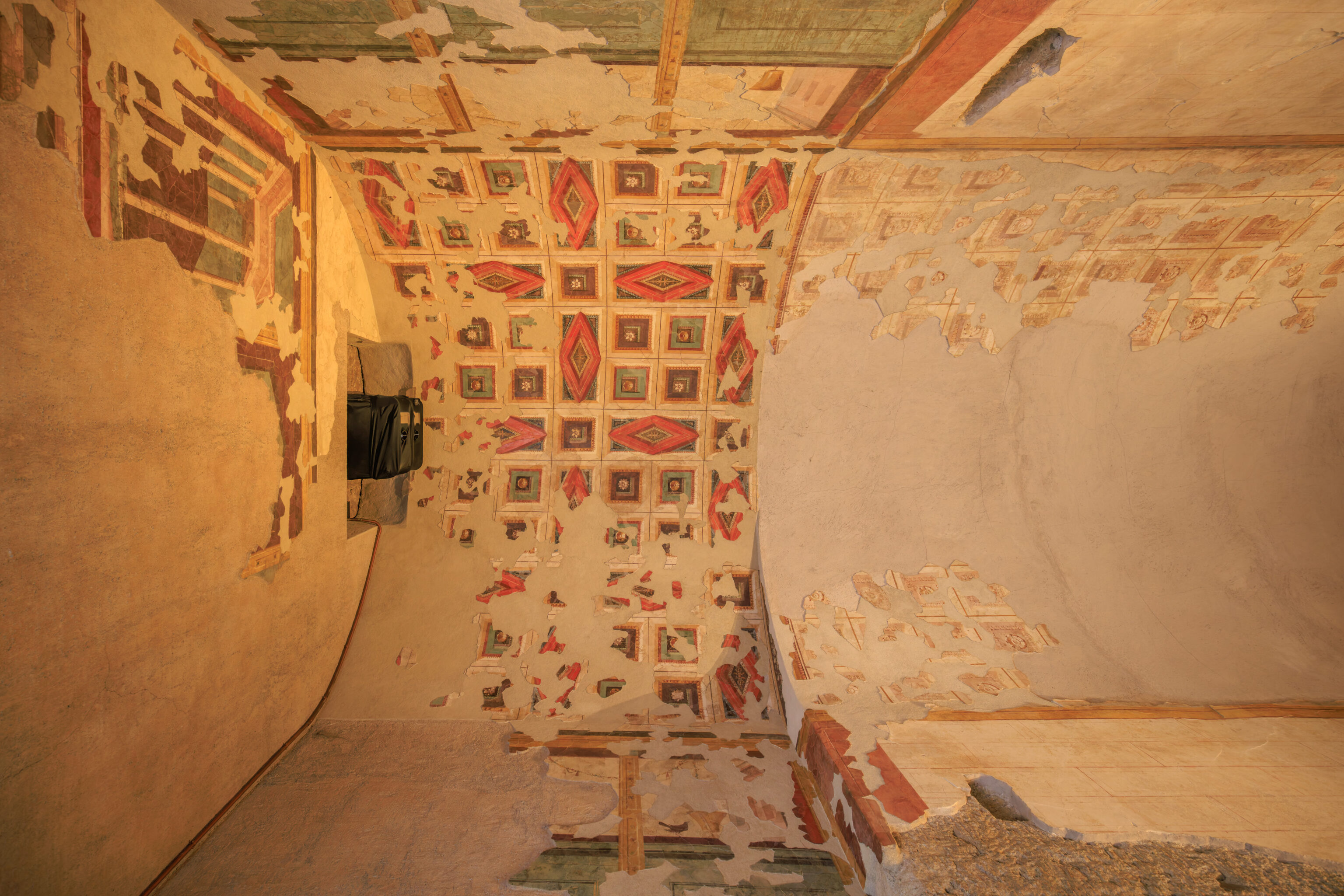

No further description of the rooms beyond that first sign was available. However, it was definitely interesting to see these rooms with their decorative walls and floor tiles. It isn’t clear if this entire area that we saw was the Private Apartments or if part of it was part of the Public Sector.

These rooms were accessible by modern exterior stairs and located southeast of the Private Apartment area. They seem to be more richly decorated and were described by a sign:

ROOMS ON THE EAST SIDE OF THE PERISTYLE.

Other public rooms in the house open onto the east side of the peristyle, more closely connected to the Temple of Apollo since they occupy one side of the sacred terrace. They are remarkable for their refined decorations and the peculiar use for which they were destined. The first towards the south corner has walls decorated with frescoes and a vault with painted coffers; it gave access to a Ramp rising to the temple terrace, connecting it directly to the house and thus reserving its use exclusively for the inhabitants of the house.

North of the Ramp and communicating with it was a large hall presenting the characteristic features of a Tetrastyle Oecus: four bases still in their original position supported pillars or columns; a ceiling covering the central vault rested on these. The hall was decorated with brightly coloured paintings, had an inlaid marble floor and was certainly the most important room in the complex. A door led from the Oecus to the adjacent bedroom to the north, of small size and modest height with walls painted in the customary Second Style found throughout the house. Above, on the first floor, was a second small room of identical size: its exceptionally refined decorations, on the walls and on the stuccoed and painted vault, were collected in fragments and patiently restored. For this reason and for its isolated position, it has been identified as a "private study" to which Augustus could withdraw. Finally, north of the little room is a small chamber with the remains of an earlier nymphaeum, perhaps also reused in the house built by Octavian.

The view to the northwest from atop the stairs, showing the entrance to the House of Augustus area.

We then backtracked out of this area and continued to the northwest, ascending a hill. The hill led to an overlook on the west side of the Palatine. From here, looking roughly to the southwest, we could see this southwestern corner of the Palatine that was being worked on.

Looking to the northwest, we could see the large dome of Basilica di San Pietro (St. Peter’s Basilica) in the Vatican. It is maybe a bit more than a mile away.

We could also see part of the top of the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II to the north.

The ruins of the Roman Forum are also to the north, on the east side of the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II.

From the overlook, we walked to the southwest. We came upon a sign that describes this area:

GARDENS AND OVAL POOL

The domus Tiberiana, in the heart of the city, boasted large hanging gardens with views over the Capitoline and the Forum. These gardens covered much of the platform on which the palace was built and which was protected from the damp earth beneath by an effective waterproofing system (cavities and air wells), brought to light by excavations. The gardens were adorned with statues and altars, some of which have been found (Palatine Museum) and various types of fountains. In one corner of the platform is an oval pool, coated in white plaster and with steps on the inside, probably used to farm fish.

The hill that we were on overlooks the Domus Flavia, where we were before.

We started to walk to the northwest as we didn’t want to go back down to where we were before.

A nice little window into the lower area to the east.

We came upon a small garden with cactuses! There was also a bathroom nearby with a queue, the first that we’ve seen since the museum by the entrance to the Palatine.

Are these oranges? It seems that March is orange season here in Rome.

We continued on through another garden area. From here, we headed to the northwest.

Up ahead, we saw an overlook which seems to often be described as the Terrazza Belvedere del Palatino (Palatine Terrace Viewpoint). This overlook is at the northwestern tip of the Palatine, meaning we’ve almost walked through the whole thing now. This overlook is the same one that we saw when we first entered the Palatine by the Arch of Titus.

There are rooms below us.

This perspective, at the start of the overlook, allows us to see to the west.

Going all the way to the edge of the overlook, it is clear that there is still a huge area below us! That huge space is the Roman Forum. There also seems to be a lower overlook below.

A gull posed for us here.

Looking to the north, we could see more of the Roman Forum below. The big structure on the right with three huge arches is what is left of the Basilica di Massenzio (Basilica of Maxentius).

Looking to the northeast, we could see the bell tower of the Basilica di Santa Francesca Romana at center, with the Arch of Titus partly visible to the right. The Colosseum is in the background.

Looking more to the east, we could see the northern edge of the Palatine on the right.

After leaving the overlook, we headed to the east. We came across a sign describing the gardens that we walked through on the way to the overlook:

FARNESE GARDENS

At the end of antiquity the Palatine was abandoned and its palaces gradually vanished, buried by collapses and vegetation. This landscape of ruins fascinated cardinal Alessandro Farnese, the nephew of Pope Paul III, who in 1542 began to purchase land on the hill and in 1565 began to lay out the Horti Farnesiorum, an Italian garden with lodges, nymphaeums and suspended walkways, atmospherically reminiscent of antiquity, in which to organize hunts and open-air picnics.

The gardens were finished between 1627 and 1635 by Duke Odoardo Farnese. The Farnese property covered the foundations of the Domus Tiberiana to the slopes of the hill. On the side facing the Sacra Via and the Forum it was surrounded by a wall with bastions alluding to the mythical settlement on the Palatine founded by Romulus. The main entrance opened into this wall and was monumentalized with a gate designed by Vignola, repositioned following the excavations in Via San Gregorio. From the entrance, a system of ramps and staircases led to the garden on the summit, passing through panoramic terraces on three levels adorned with statues, reliefs, flower beds and nymphaeums fed by the Acqua Felice aqueduct, extended onto the Palatine by the Farnese family in 1588. Today the garden has lost its original appearance following the installation of cultivations in the 17th century and the archaeological excavations which have continued from the 18th century until the present. In 1861 the Horti were sold by the Farnese family to Napoleon III and by the latter to the Italian government in 1870, becoming a part of the large archaeological park of central Rome.

While walking through the garden area, we saw a modern looking building along with stairs that went down below the garden area. That building, actually, a pair of buildings, hold small exhibition spaces. We briefly looked inside. They held art that we didn’t find particularly relevant to this historical site. This patio area is on the east side of those two buildings.

From the patio, we could see a bit of the Colosseum to the east. The big wall to the left of the Colosseum is the side of the Temple of Venus and Rome.

We walked to the southwest down a slope to begin leaving the Palatine. On the way, we came across another sign describing the garden:

ABANDONMENT AND NEGLECT TURNED THE PALATINE HILL INTO A RURAL LANDSCAPE OF FIELDS AND VINEYARDS. IN THE 1 MID-SIXTEENTH CENTURY THE FARNESE FAMILY HAD SOME OF ITS AREAS DEVOTED TO GARDENS, PLACES OF REST AND PLEASURE. THE FARNESE GARDENS FEATURED JASMINE, ROSES, BITTER ORANGES, MULBERRIES AND ELMS. THEY WERE ARRANGED ON TERRACES WITH NYMPHAEMUS, FOUNTAINS AND TWO AVIARIES PLACED SYMMETRICALLY WICH FORMED THE MONUMENTAL FACADE TOWARDS THE ENTRANCE. THE CURRENT ARRANGEMENT IS THE WORK OF GIACOMO BOΝΙ (1859-1925).

The aviaries may be the two buildings that are used as exhibition space.

We actually ended up by the Domus Flavia again.

We briefly walked around this northwestern section as we hadn’t been by here earlier.

We came across a sign describing the so-called basilica:

DOMUS FLAVIA. SO-CALLED BASILICA

The so-called Basilica takes its name from the architecture of its interior, typical of basilicas: it was divided into three hails by coloured marble columns with an apse at the end closed by a balustrade.

Traces of the marble veneer survive on the walls and part of the floor made of large slabs of coloured marble was preserved until the 19th century. A modern staircase leads to a room beneath, covered by the palace, known as the "Hall of Isis" and decorated with frescoes of the Augustan period on Egyptianizing subjects (on display in the Loggia Mattei). This room may have been used for settling legal disputes, pre-sided over by the emperor.

This may be part of the so-called basilica, as seen from the side?

We continued to the northeast to descend off of the Palatine.

We walked by this fountain, described by a sign as the Nymphaeum of the Mirrors:

NYMPHAEUM OF THE MIRRORS

From the garden of the Horti Farnesiani, covering the foundations of the Domus Tiberiana, a series of stairs and ramps led down towards the so-called Clivus Palatinus and the gardens facing the Colosseum. On this side of the hill are the remains of a semi-circular nymphaeum built in imitation of a grotto up against the ancient walls. Opening into the wall of the nymphaeum are niches which hosted statues of Satyrs holding up mirrors, which gave the nymphaeum its name. Water fell like rain from the top of the vault, now lost, encrusted with coloured stones and enamels; water also gushed up at the base of the niches and, unexpectedly, from little holes in the floor in front of the nymphaeum, also made of a mosaic of coloured stones.

Nearby, we came across a sign for the Cryptoportico Neroniano (Neronian Cryptoporticus):

NERONIAN CRYPTOPORTICUS

The Cryptoporticus is one of the most distinctive monuments of the Palatine. It is an underground corridor, 130 metres in length, illuminated by basement windows. It connects the south side of the Domus Tiberiana to the so-called House of Livia. This covered passageway served to link the different parts of the imperial Palace in the Julio-Claudian period. Originally the vault was covered with fine white stucco, depicting cupids within decorative frames. Only a few fragments remain. While this stucco decoration has generally been dated to the age of Nero, it probably relates to an earlier period, the first half of the 1 century AD.

It had opening times listed from 9am to 4:30pm, though unlike the House of Augustus, no ticket is required for entry. We decided to take a look as the sign was pretty compelling. We then came across another sign that describes some of the structures on the Palatine, including the House of the Griffins, which we saw earlier. Or rather, we saw its large remaining wall. The sign reads:

The Aristocratic Houses of the Palatine Hill

When Octavian came into possession of the residence of the orator Hortensius Hortalus in 42 BC after its confiscation, the Palatine must have been a vast residential district, prized for its elevated position, set back from the central Forum square. The presence of illustrious owners recorded by the ancient sources (including Cicero) gradually led (due to a phenomenon of social emulation) to the purchase of all the available building plots and thus the need to construct large multi-storey residences. These houses, arranged around an atrium, had residential rooms (dining rooms or triclinia, and bedrooms or cubicula) in the basements, particularly prized because they provided insulation from the summer heat. The subsoil of the Palatine has thus preserved some sectors of these luxurious domus of the first half of the 1st century BC, whilst their upper storeys were destroyed or transformed when the imperial palaces were built on top of them (as is true of a house recently discovered beneath the Domus Tiberiana. fig. 1, nº 1); the best known is the so-called House of the Griffins (fig. 1, n°2 and fig. 2), which takes its name from the subject of its fine stucco decorations). In all these houses. the painted decorations served to express the prestige of the owner, the dominus: drawing on the repertoire of the Hellenistic palaces and on the techniques used for stage sets, these paintings mimicked genuine architectural features, arranged on several storeys, whilst the background imitated valuable marble panelling, creating a play of allusions between the decorative schemes of floors and frescoed walls.

These are the most ancient wall paintings belonging to the so-called II style, one of the four into which conventionally the Roman painting production is subdivided. Perhaps developed exactly for the aristocratic dwellings of the Palatine, it will find its highest artistic expression in the houses of August and Livia.

We walked through a somewhat long and rather dark tunnel.

The tunnel led to a passageway that was open to the elements. There was a sign that described ancient Roman interior decor:

The colours of dwelling

To the modern visitor, Roman houses appear strangely populated by painted images rendered in bright colours. often in contrasting tones. The experience of walking around Roman domestic spaces thus forces us to find a new "way of seeing through which to decipher the meaning of these many colours and numerous representations of places and people, somewhere between reality and fantasy. The first key to interpreting them lies in the existence of established pathways, both physical and visual, where the choice of decorations underlined the hierarchy of internal spaces to anyone entering the houses (from the more public rooms to the more private ones). Wall paintings, an essential complement to the masonry that they covered. immediately began to imitate additional architectural forms against a closed background covered in valuable marble panels, suggesting new forms of space. Very soon, the contents of paintings (which reached Rome as booty after the conquest of Greece in the 2nd century BC) invaded the space of entire walls. Here they established a dialogue with numerous other motifs developed by an artisanal tradition that was capable both of innovating and simultaneously of copying models and creating "universal" repertoires for the whole Roman world. The powerful medium of images was thus entrusted to painters who were often anonymous, whose efforts were in demand from the wealthy owners who wished to show off to their peers the most fashionable decorations, thus marking their belonging to a shared system of cultural references. It was the residence of Octavian (later the emperor Augustus), the first true palace on the Palatine hill. which created a new taste in paintings: the walls opened up into theatrical vistas with little shrines and porticoes. framing depictions inspired by traditional religion and by the exotic world of the cults of Isis. This was a new art that assimilated and recreated the paintings of earlier periods, from the great works of Greek artists to the tiny decorations on textiles used for furnishings, to create an original style.

We then walked through another tunnel. While these tunnels were impressive due to their age, they aren’t particularly interesting to walk through. However, at the end of this tunnel, we came upon the entrance to the House of Livia! We saw this building earlier but never found its entrance.

A sign describes the artwork within:

THE PAINTINGS

The frescoes in the House of Livia, dating to around 30 BC, are among the most important examples of the advanced Second Style in Rome. The Tablinum is also known as the "Room of Polyphemus" for the painting on the back wall, now in a poor state of conservation, showing the cyclops Polyphemus pursuing the nymph Galatea. On the right-hand wall, at the centre, is lo facing Argus, her guardian; Mercury, arriving from the left, is about to free her. At the sides of the wall are backdrops of illusionistic architecture and small panels with ritual scenes. In the right-hand room, the decorations are organized around a portico: between the columns are luxuriant plant festoons adorned with ribbons and cult objects. Above runs a monochromatic landscape frieze on a yellow background, very rare of its type, with scenes of everyday life in Egypt (camels, sphinxes and a statue of Isis can be seen). The decorations in the left-hand room show winged fantasy figures, human and animal, ending in elegant plant tendrils; this is a style of painting strongly condemned by Vitruvius as unnatural and unrealistic. The Triclinium is remarkable for the spatial depth of its decorations, with sacred and rural landscapes; on the long wall is the betyl, the aniconic symbol of Apollo, a particular favourite of Augustus; there are also still lives in the form of glass jars full of fruit. A simpler architectural scheme adorns the walls of the atrium and the vestibule.

The artwork on the walls, still visible 2,000 years later, are quite impressive. Also, large amounts of tile remain here from that time. A sign describes this structure, which was the private living quarters of Livia, the wife of the first Roman Emperor Augustus:

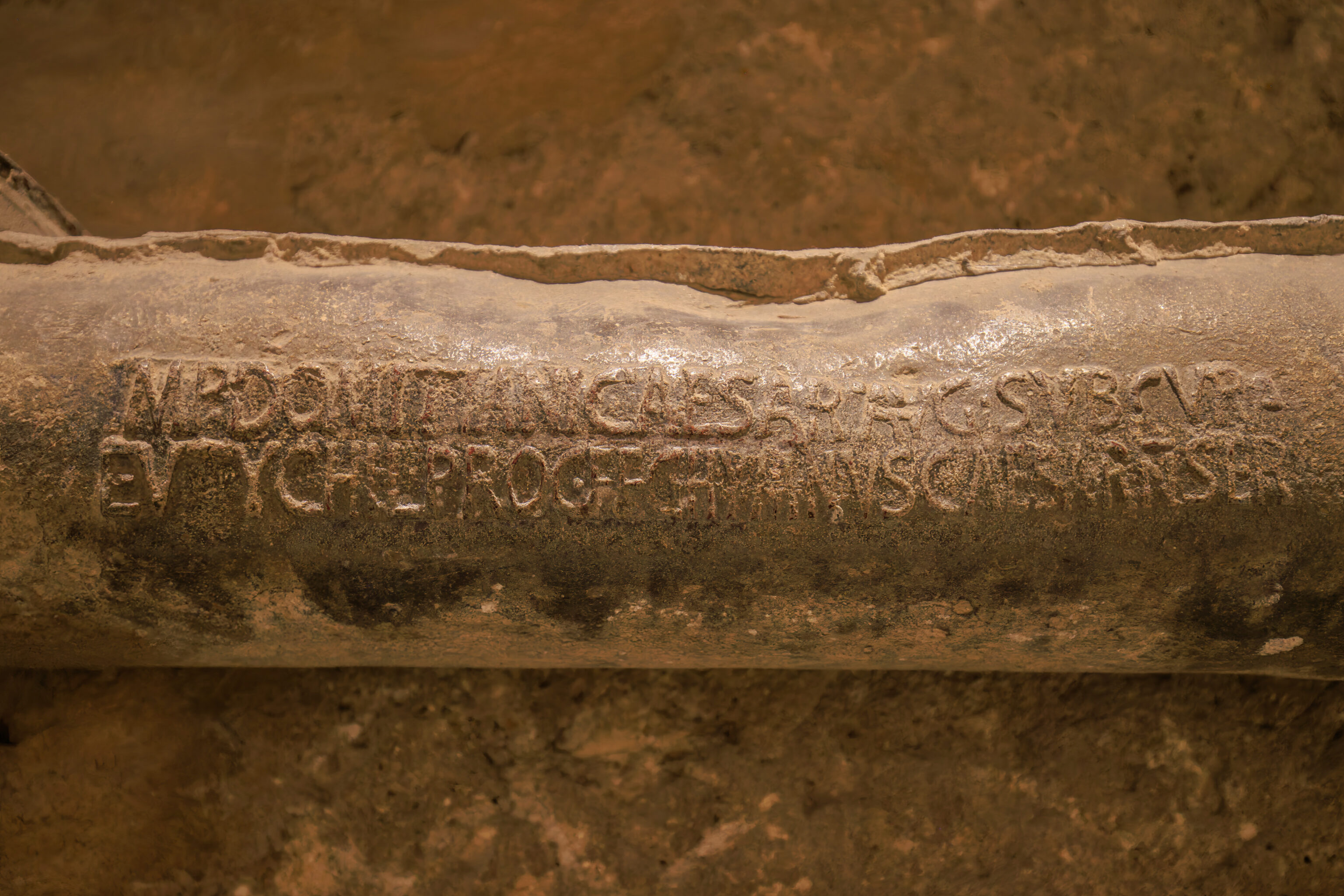

HOUSE OF LIVIA

This rich private domus (house) of the 1ª century BC, brought to light by P. Rosa's 19th-century excavations, has been attributed to Livia on the basis of the name Julia Augusta stamped on a lead pipe on display in the tablinum, found in a gallery connected to the house. We know from Suetonius (Life of Augustus 52-53) that Augustus married Livia Drusilla immediately after divorcing Scribonia; he took his new wife from her husband Tiberius Nero, with whom she had already had a son (the future emperor Tiberius) and was pregnant with a second child. Suetonius adds that Augustus "loved Livia and cherished her with unusual perseverance". Unfortunately, while he had fathered Julia with Scribonia "he had no children with Livia, though he desired this immensely".

The House of Livia can be considered an apartment reserved for Augustus' wife within the Augustan complex; Livia is known to have played an extremely important role in the political life of Rome even after her husband's death. The house consists of a rectangular atrium; opening onto it are four rooms with mosaic floors and painted walls: at the back is the tablinum at the centre, with two symmetrical rooms on either side. To the right of the atrium is the triclinium, restored and reopened for the Augustan bimillennium after being closed for decades.

On the upper floor are bedrooms and service rooms accessed by a staircase located between the atrium and the triclinium.

These are segments of the lead pipe.

This protective covering reads, in Italian:

RIVESTIMENTO DI TEGOLE SU CUI ERA APPLICATA LA DECORAZIONE PITTORICA DELLE PARET: MERIDIONALE ED ORIENTALE

Which Google translates to:

TILES COVERING ON WHICH THE PICTORIAL DECORATION OF THE WALLS WAS APPLIED: SOUTHERN AND EASTERN

We have no idea what this is supposed to mean. There are arrows and a square marked on the left side of the cover, which seems like it is supposed to indicate something under the transparent cover.

So while the Neronian Cryptoporticus wasn’t particularly compelling, it at least led us here! After exiting, we realized where we were. The entrance was on the northeast side of the building, basically wedged between the building and the hill above. When we saw the building from the other side, we had actually looked around here but it looked like it was just another area being used for storage! We never saw the entrance. We were also on the hill above later on, and even have the entrance side of the House of Livia in a photo, but again never saw the actual entrance.

Having ended up by the Domus Flavia again, we again headed northeast to leave the Palatine.

We actually noticed what seemed like parrots earlier. And, we managed to apograph one! Photographing birds from afar with a wide angle lens generally doesn’t yield good results but at least you can tell that this is some sort of parrot!

The view looking back as we walked away from the Domus Flavia.

We didn’t actually leave the Palatine just yet. We ended up one level below the two exhibition spaces and the garden above. This put us at the northeastern edge of the Palatine. A sign describes this area and fountain:

TEATRO DEL FONTANONE

At the top of a second ramp, on the same axis as the original entrance to the Garden, lies a panoramic terrace adorned with a monumental architectural façade. At the centre of the wall placed against the hillside, decorated with graffiti, is a tall recess which hosted a fountain consisting of a vertical sequence of basins from which water flowed in cascades. At the sides of the fountain two flights of steps lead to the garden above. Ancient sculptures in coloured marbles decorated the façade, including statues of Isis in the niches at the top of the stairs and statues of kneeling Persians holding flower pots.

We were directly across from the Basilica of Maxentius.

We headed northeast to actually leave the Palatine this time, passing by this plant with odd looking flowers.

We passed by these ruins which were formerly buildings along a road known as the Nova Via (New Road).

ROOMS AT THE INTERSECTION OF THE CLIVUS PALATINUS AND THE NOVA VIA

After the fire of AD 64 which changed the appearance and function of this part of the city, long rows of shops, whose brick walls survive, were built along the road ascending to the Palatine and that at the foot of the domus Tiberiana, traditionally known as the Nova via. Previously, this area had been home to some luxurious private domus. Excavations at the intersection of these two roads have brought to light the remains of a luxurious house dating to the 1st century BC – now reburied - with mosaic floors and a courtyard with a marble-clad pool.

This is how the Nova Via looks today. We decided to continue further north to a path that was a bit further downhill from here, the Via Sacra (Sacred Path). In retrospect, this probably was a mistake. We didn’t realize it at the time but this path leads to areas that don’t seem to be accessible via the path below.

A sign here describes the concrete foundations built in this area:

NERONIAN FOUNDATIONS

The concrete foundations that run from the Forum around the corner towards the Palatine, alongside the Arch of Titus, probably pertain to the enormous portico that, according to the ancient sources, Nero had constructed as the vestibule of his Domus Aurea. It extended for a length of c. 300 metres from the Forum to the area of the Temple of Venus and Roma, and enclosed the colossal statue of Nero, 120 ft (c. 35 metres) high, that rose in the location where the temple later was built.

We passed by the Arch of Titus, returning to the nearby museum to use the bathrooms there. By now, it was 4pm and getting close to closing time.

The view to the west by the arch, with the terrain blocking some of the lower portions of the Roman Forum.

After walking west a bit, looking to the left, we could see where we just descended from.

And, looking to the northeast, we could see the Basilica di Santa Francesca Romana and its tall bell tower. This church has an entrance that is outside of the Palatine and Roman Forum so that entry tickets are not required to visit.

This area is described as the Horrea Vespasiani (Vespasian’s Warehouses):

HORREA VESPASIANI

After the fire of AD 64, the slopes of the Palatine became a commercial area. It was probably Vespasian who built a vast building here supported by pillars, perhaps used as a warehouse for imperial goods. A few years later Domitian turned Vespasian's warehouses (horrea Vespasiani) into a shopping centre, perhaps for foodstuffs, with numerous shops on two levels, arranged around two identical courtyards. Other shops faced onto the external porticoes.

These palms kind of resemble giant pineapples!

This is simply described as the Portichetto Medievale (Medieval Portico):

The remains of this building were perhaps part of a larger aristocratic residence from the Middle Ages (12th century AD). Five preserved brick arches open along the Via Sacra. The lowering of the road level of the area, due to the excavations of the late 19th century, has made visible the foundations of the portico, originally covered by the road surface.

The view looking more or less to the southwest as we walked down the Via Sacra. If you look closely at the Terrazza Belvedere del Palatino, the big overlook at the northeastern corner of the Palatine, you may notice that two levels down, there is glass covering the arched openings. We realized we missed a whole area there.

The same view from a bit further down the road.

This building is thought to be a temple built by Emperor Maxentius to honor his son that died as a child:

SO-CALLED TEMPLE OF ROMULUS

On the basis of a depiction on a coin this building – unusual in shape for Roman architecture – is identified as the temple built by the emperor Maxentius in AD 307 in honour of his son who died in childhood. The circular building is flanked by two apsidal halls opening onto the front with little porticoes decorated with porphyry columns. The bronze door is original and the lock still works. Pope Felix V turned the monument into the vestibule of the Church of Sts Cosmas and Damian but the entrance to the Forum was reopened in 1879.

The temple can be visited, however, it closed at 3:45pm. it might also be open on free entry days, although that seems a bit odd.

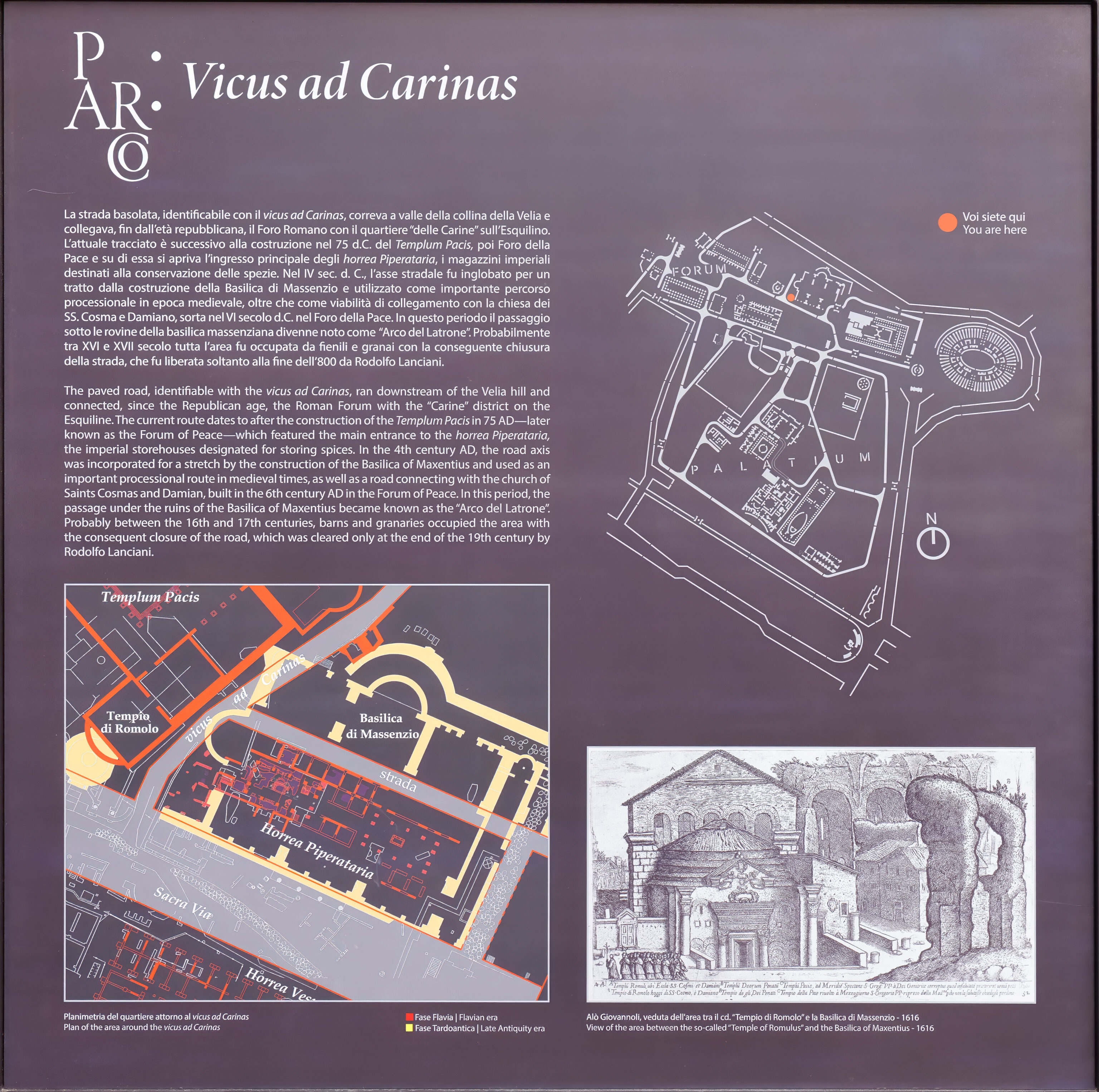

The sign below, seen around the temple, describes this general area that we are at:

The paved road, identifiable with the vicus ad Carinas, ran downstream of the Velia hill and connected, since the Republican age, the Roman Forum with the "Carine" district on the Esquiline. The current route dates to after the construction of the Templum Pacis in 75 AD-later known as the Forum of Peace-which featured the main entrance to the horrea Piperataria, the imperial storehouses designated for storing spices. In the 4th century AD, the road axis was incorporated for a stretch by the construction of the Basilica of Maxentius and used as an important processional route in medieval times, as well as a road connecting with the church of Saints Cosmas and Damian, built in the 6th century AD in the Forum of Peace. In this period, the passage under the ruins of the Basilica of Maxentius became known as the "Arco del Latrone". Probably between the 16th and 17th centuries, barns and granaries occupied the area with the consequent closure of the road, which was cleared only at the end of the 19th century by Rodolfo Lanciani.

These small rooms are described as the so-called carcer (prison) because of a likely misunderstanding:

SO-CALLED CARCER

The three small rooms opening onto a corridor with walls made of large tufa blocks and travertine door and window frames are generally ascribed to a Carcer; this is an error as tradition attests the existence of only one prison in Rome, the Tullianum on the slopes of the Capito-line Hill. Thought by some to be a brothel, these are probably the service rooms of a Roman house, perhaps used as a cellar or to house slaves.

This area is described as having been used for burials though there’s nothing visible to us that suggests that other than this sign:

ARCHAIC BURIAL GROUND

Numerous tombs dating to between the 9th and 7th centuries BC were excavated in this area in 1902, with two types of burials: cremations and inhumations. The former, the oldest tombs, usually contained a funerary urn in the form of a hut with the remains of the deceased; in the inhumations the body was buried directly in the earth or in wooden or tufa coffins. The funerary equipment found in the tombs (clay and bucchero vessels, bronze jewellery) is held in the Forum Antiquarium (display under preparation).

We decided to turn left and walk to the south to see if we could access the area that we missed below the Terrazza Belvedere del Palatino.

We ended up here at La Casa Delle Vestali (The House of the Vestals), which occupies this space below the Palatine. A sign helpfully explains:

THE HOUSE OF THE VESTALS

The house of the Vestals is located next to the temple of Vesta. Together the temple and house formed a single complex, the atrium Vestae. The structure that can be seen today was built in brick-faced concrete after Nero's fire in AD 64. It was then reconstructed by Trajan and restored by Septimius Seve-rus. In AD 394 Theodosius I, a Christian emperor, ordered it to be abandoned. Bedrooms, reception rooms with heating systems and marble paving, and service areas such as kitchens and a mill were arranged on several levels around an arcaded courtyard, decorated with fountains and statues of the most famous Vestals of the past.

Who exactly lived here? Le Vergini Vestali (The Vestal Virgins). The same sign elaborates:

THE VESTAL VIRGINS

The priestly order of Vestals dates back to Romulus or Numa (8th - 7th centuries BC). Priestesses had to be young aristocratic virgins, and were chosen by the Pontifex Maximus when they were between the ages of 6 and 10. Their service as priestess lasted for 30 years and brought them wealth and privilege, but also required chastity and observation of rituals. The Vestals kept alight the public fire that burned in the temple of Vesta, looked after sacred objects and celebrated annual festivals. On these occasions the Vestals prepared the mola salsa, a mixture of flour and salt, which was sprinkled on sacrificial victims.

The pontifex maximus referred to above is the highest person of the Roman religion. In later times, the same term was used for the Pope as head of the Roman Catholic Church.

Parts of statues remain here in various states.

The view to the west from the eastern end of the House of the Vestals.

A bit of marble flooring remains here.

A path runs at ground level next to the Palatine with some rooms dug into the side of the hill. Various artifacts are displayed in these rooms.

A low ruined wall separates this passageway from the grassy area outside.

There is no way up. This was about as close as we could get.

We headed back out of this area to continue walking to the west through the Roman Forum. We saw a sign on the western end of the House of the Vestals that describes where we are here:

Before the fire in the reign of Nero the house of the Vestals had a different shape, size and orientation. The oldest surviving structure dates to the 6th century BC, it was then rebuilt from tuff blocks in the 3rd century BC, and redesigned in the late Republic-early Empire. Recent excavations have revealed a hut dating to the mid-8th BC century. This may have been the earliest home of the priestesses, Here, beneath the imperial paving with its chambers for the heating system, the remains of walls and mosaics of the Republican house of the Vestals were found.

As we continued walking, we came upon many stone pieces lying on the ground.

We were now northwest of the Palatine.

These three very tall columns were visible from rather far away. We were now right in front of them.

It was now 4:45pm and there still seemed to be quite a bit ahead that we hadn’t seen yet.

We came across a small structure that was identified by a sign as the Tempio del Divo Giulio (Temple of Divine Julius, though translated simply as the Temple of Caesar). The sign was only legible in Italian. It read, translated using Google:

TEMPLE OF CAESAR

Caesar, assassinated in 44 BC in the Curia of Pompey in the Campus Martius, was cremated in the Forum, in front of the Regia. On the site Augustus erected a temple, dedicated in 29 BC. Built on a high podium, with six columns on the front, it was decorated with the rostra of the ships of Anthony and Cleopatra captured by Augustus, two years earlier, in the battle of Actium. The altar, located in the semi-cycle of the podium, replaced the commemorative column. Stairways on the sides led to the interior of the building, of which today only the cement core remains.

We went in to take a look. There isn’t really much of anything inside but there were offerings of coins and flowers.

There were more stone pieces strewn about…

Just a random well decorated stone piece sitting atop another stone piece which is inscribed with text.

We came across a sign and learned that this set of 3 columns belongs to the Tempio di Castore e Polluce (Temple of Castor and Pollux), the two sons of Jupiter:

TEMPLE OF CASTOR AND POLLUX

According to legend the two brothers, sons of Jupiter, were seen watering their horses at the Spring of Juturna in the Forum after helping the

Romans against the Latins and Etruscans at the Battle of Lake Regillus

(496 BC). In their honour the dictator Aulus Postumius Albinus built a

temple -dedicated in 484 BC- which was transformed several times

over the centuries. The high podium dates to its reconstruction by Me-

tellus in 117 BC; another important reconstruction took place under

Tiberius, to whom we can attribute the three Corinthian columns and

the fine entablature visible on one side of the temple, which had two

flights of stairs at the sides.

This next area, to the west, was the Basilica Giulia (Basilica Julia)

BASILICA JULIA

The Basilica Julia, like all the other basilicas, was a building to be used as a covered space for all different kind of social functions; it was begun by Julius Caesar in 54 BC in place of the Basilica Sempronia and the

tabernae veteres. It was rebuilt by Augustus, who dedicated it in 12 BC.

The basilica suffered several fires over the centuries and was restored in

the 4th century AD by Diocletian and again after Alaric's sack of Rome

(AD 410). The rectangular building was surrounded on all four sides by

a double colonnaded portico, of which only the bases of the pillars sur-

vive. Remains of the tabernae, small rooms used as offices and meeting

places, can be seen on the south side of the building.

There isn’t much left here, though these stairs that run the length of the building are pretty prominent. This was as far as we went as it was 5pm and the staff were starting to shut the place down.

We started heading towards the nearest exit, though we stopped to look at whatever was nearby on the way. A sign indicate that this was a Tabernae sul fronte della Basilica Aemilia (Tabernae in front of the Basilica Aemilia):