After breakfast at the Hampton Locarno, we took the train to Milan and checked in to the Excelsior Hotel Gallia, next to Milano Centrale. We walked through the historic city center, seeing the Piazza del Duomo, Basilica di Santa Maria delle Grazie, and Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio.

Leaving Locarno

After waking up at the Hampton by Hilton Locarno, we headed downstairs for one final breakfast before checking out. They actually had a new dish today, something like stewed beef.

After breakfast, we did a bit of final packing and checked out. Overall, it was a great stay. The room rate, including taxes, was just under $200 USD per night. That’s significantly cheaper than comparable hotels here in Switzerland, particularly for one that was new and with a modern interior. The location was a bit out of the way, requiring a bus ride to get to the train station, but overall it wasn’t too much of a problem as bus service was frequent.

The hotel did have some weird design elements. Its unfortunate that the windows were so narrow as it would have been nice if they were normal sized! We had a view of the mountains and it would have been nice to have more natural light. Also, the design of the windows, with the glass kind of set in from the exterior of the building, meant that there was a huge natural ledge for birds to stand on and to poop on. A minor point though, we didn’t pick this hotel for the windows or the views.

Ultimately, if we ever find ourselves in the area in the future, we’d definitely consider staying here again.

We walked over to the Ponte Maggia bus stop one last time to catch the next bus to the Locarno train station. One humorous note for English speaking folk, the acronym for the local transit operator is Ferrovie Autolinee Regionali Ticinesi, aka, FART.

After arriving at the Locarno train station, we waited for the next train to Milan. We were a bit early as the next departure, the RE80, wasn’t until 9:22am.

We walked down to the far end of the train before getting in right after the train arrived. It was empty for awhile but did end up filling up a fair amount.

The train didn’t turn out to be the greatest platform for taking photos from, primarily due to how low the windows relative to whatever was along the tracks along with reflections on the windows. Still, we got a few descent scenes.

Milano

We arrived at Milano Centrale at around 11:20am. After spending the last three days in small cities and towns, we were finally in a big city once again.

The station interior is quite grand. Perhaps the original Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan was like this before the building was demolished!

We walked outside and were quite impressed by the station’s exterior.

There is a big apple outside. It’s kind of like the Apple logo except the missing part has been reattached! The sculpture is The Apple Made Whole Again by Michelangelo Pistoletto. It was made for Expo 2015 which was held in Milan and moved to the current location in 20161.

Our hotel, the Excelsior Hotel Gallia, was on the west side of the piazza in front of the station. We walked over to see if we could check in. Our room was not ready so we dropped off our bags and visited the bathrooms before heading back out.

We decided to go visit the historic area of Milan, perhaps about two kilometers away to the southwest. Rather than take the Metro from here, we walked a few blocks to the southeast to the Via Vitruvio tram stop. It turns out that the tram was not running here today!

So, we decided to continue walking to the southeast to reach the Lima Metro station. We came across a large market so decided to walk through it. Afterwards, we decided to eat before continuing on. We visited The Kitchen Milano, which was just a block away. It turns out that this restaurant is owned by a Chinese couple, both of whom seem to have been adopted in Italy according to their restaurant’s website.

We decided to order a risotto and a calzone. A small appetizer was provided.

The risotto seemed more or less typical of the risotto we’ve had before, although it was more saffrony than most.

We ordered the calzone mainly because we haven’t had it yet in Italy. The calzone was pretty different from the few places in the US where I’ve had it, particularly DP Dough and the defunct Old Chicago in Boulder. It was a bit like a sandwich or panini, just with a pizza-ish crust, and not sealed.

We also had some dessert.

And coffee because after all this is Italy!

Piazza Duomo

After lunch, we finally reached the Metro station and took Line 1 (Red) to the Duomo Metro station. We exited the station on the north side of the Piazza Duomo. There were many people in the piazza! It looked like there was something going on, though we couldn’t tell what exactly it was.

We walked over to the area in front of the Duomo to take a look. This area was partially fenced in and elevated a few steps above ground level so it was a good place to see what was going on and also to take a look at the front of the Duomo.

The Duomo was intricately decorated, particularly the large closed doors in front.

So, what was going on here on the piazza in front of us?

After watching for awhile and a brief conversation with an Italian with some iffy English, we understood that these were Inter Milano fans and there was going to be Champions League finals match against Paris Saint-Germain today!

We watched them for awhile before moving on.

The Duomo requires tickets to enter. We didn’t have tickets as we weren’t sure as to our exact plans in Milan. So, we went to find the ticket office. We had to ask for directions as it wasn’t obvious where it was. It was on the south side of the cathedral. So, we walked around via the east side to get there.

They were sold out for today, though there was ample availability for tomorrow. So, we bought tickets from a kiosk. It probably makes more sense to just buy tickets online as the kiosk ticket is basically just a long receipt, something that can be more easily lost than an email or PDF.

This shield was on a nearby building across from the Duomo. It seems to depict a snake or dragon eating a man? It is apparently a biscione, which Wikipedia translates as “big grass snake.” This symbol is the coat of arms of the Visconti, who were Dukes of Milan about 600 years ago. This coat of arms lives on as the symbol of Milan.

We continued circling around the Duomo.

After returning to the Piazza del Duomo, we cautiously went to take a closer look at the Inter Milano fans and their very large flag. They seemed quite energized but peaceful. Football rioting is possibly limited to after winning a game? Or losing it?

We also went to take a closer look at the large equestrian statue on the west side of the piazza. It depicts Vittorio Emanuele II, the first modern King of Italy. It is quite a bit smaller than the huge Monumento a Vittorio Emanuele II in Rome, which we visited almost three months ago.

We couldn’t walk all the way around the statue as part of the area was fenced off for Radio Italia Live, which took place yesterday evening.

We walked over to take a look at the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II on the north side of the piazza. This shopping arcade dates back to the late 19th century.

We went in to take a look. The arcade is quite an impressive and beautiful structure, filled mostly with high end shops.

We exited the arcade on the opposite side. This building is the Palazzo Marino, the current Milan city hall, but was built back in the 16th century. The 2026 Winter Olympics and Paralympics are scheduled to be here in the region which explains the Olympic rings and Paralympics symbol.

A fountain with statues was at the center of a circle of trees in the middle of the small piazza by the palazzo and arcade, the Piazza della Scala. So, who is this guy?

We had to look it up on Google Maps to identify the subject of this fountain. It turns out to be Leonardo da Vinci!

It does say Leonardo on the front of the main statue. He had worked in Milan and had been employed by Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan.

We decided to next head over to the Basilica di Santa Maria delle Grazie by walking east over to the San Babila Metro station and taking Line 1 (Red) west to Cadorna Station.

These eight figures have some similarity to the caryatids at the Acropolis, which we saw recently in Athens. This building is the Casa degli Omenomi.

A sign explains further:

This house is named after the eight large telamons or omenoni ("big men") sculpted by Antonio Abondio which embellish the ground-floor street front. Built around 1565, it was the residence and workshop of Leone Leoni, the celebrated sculptor for Charles V and Philip II of Spain who moved to Milan after an eventful and turbulent life at the court of kings but also as a galley slave.

The visually striking reliefs on the lower level contrast with the piano nobile above, with its Ionic columns, recesses and windows with rounded tympana. The words under the cornice read "Calumny Torn to Pieces by Lions", a direct reference to the irascible temperament of the owner ("leone" means lion). The building also housed the fine works of art collected by Leone and his son Pompeo: ancient artefacts, paintings by great artists of the day such as Titian and Correggio, but most notably Leonardo da Vinci's Codex Atlanticus, now in the Ambrosiana Library.

We continued on…

We came across a large disc sculpture in front of headquarters of the Banca Popolare di Milano, aka BPM. The sculpture is Il Grande Disco by Arnaldo Pomodoro. The design reminded us of the Sphere Within a Sphere at the Vatican Museums, which we saw during our visit. And indeed, these two works were made by the same artist!

The church in the background here is possibly the Chiesa di San Carlo al Corso.

This church, which was to the east, is the Chiesa di San Babila.

We’ve reached our destination! The Piazza San Babila is right above the San Babila Metro station.

Basilica di Santa Maria delle Grazie

After taking the Metro to Cadorna Station, we headed up to ground level. We ended up at a piazza in front of the station. We happened to see a historic tram, what we would call a streetcar in the US, pass by. It appears to be from the late 1920s based on its number, #1898.

There were large colorful decorations outside. Almost a bit like Google without the blue.

After a slight navigational error, crossing the street when we didn’t need to, we walked into Venchi to get some gelato. We got mango, strawberry, and hazelnut from Piedmont. Venchi is perhaps not the absolute best gelato but in our experience has been consistently excellent.

We walked to the southwest to reach the Basilica di Santa Maria delle Grazie.

We entered via the east side which led into a cloister. This church is known for having Leonardo da Vinci‘s Last Supper. There is a museum here dedicated to this painted mural. Tickets are reported to be released by the quarter so you need to buy them fairly quickly once they’re available.

Altar-piece: Virgin Mary with Child, St. Vincent Martyr and St. Vincent Ferrer, by Coriolano Malagavazzo (1595).

The frescoes (beginning of XVII century) were painted by the Fiamminghini brothers; on the left, two of Ferrer’s miracles: he unmasks an heretic preacher; he gives life back to a child.

On the right, two episodes of deacon Vincent’s martyrdom. (On the right pillar: there was St. Dominic, destroyed during World War II)”

Altar-piece: the Crucifixion, by Giovanni Demio of Schio; to him belong the wings of the vaults with the 4 Evangelists and 8 Sibyls; the lateral lunettes: Noli me tangere” on the right; Disciples of Emmaus on the left.

On the walls elegant angels, in earthenware covered with stucco, carrying the instruments of the Passion (unknown master). Remarkable is the majolica tiled floor. The scars of the bombardment of august 1943 are still evident.

On the pillar up right: B. Antonio of Asti martyr (XIV century)”

Altar-piece: the Deposition from the Cross, by Caravaggino (1616). Originally was figuring “The Crowning of Thorns Coronation” by Tiziano, stolen in 1797, now at the Louvre.

The frescoes of the vaults and of the walls were painted by Gaudenzio Ferrari (1542) with scenes from the Passion: the scourging, “Ecce Homo” on the right; the Crucifixion on the left.

On the right pillar: Dominican praying in front of a picture of the Virgin Mary)”

Altar-piece: St. Michael defeats Satan, by an imitator of the Parmigianino (approximately 1560).

On the vault: the nine angelic choirs, by unknown painter.

On the lateral lunettes: on the left the expulsion of the rebellious angels; on the right the sending of the Archangel Gabriel, painted by B. Luini’s sons,

On the right pillar: B. Antonio of Savignano, martyr (1374)”

At the entrance: a gate cast in bronze (approximately 1669) formerly the railing of the high altar until 1935.

Altar-piece: marble monument of the Virgin Mary received into Heaven and Eve at her feet, by Arrigo Minerbi (1941).

On the sides: cenotaphs of Senator Ettore Conti and his wife Gianna Casati, by Francesco Wildt (1935), in memory of the illustrious benefactors of the church, that was completely restored (1935-1937) and rebuilt after World War II.

On the right pillar: B. Roboaldo d’Albenga (XV century)”

Altar-piece: St. Dominic, holding the Rosary, receives the book and the stick of the evangelic preaching from the St. Apostles Peter and Paul, by Carlo Pontoia (approximately 1730).

On the walls, four fragments of the glory of the Dominican Saints, by Francesco Malcotto, that were in the apse of the choir before the Conti’s restoration (1935).

On the right pillar: B. James of Monza (XV century).

Chapel restored with the contribution of Mr. P. A. Mettel, in memory of A. Benedetti Michelangeli (1996).”

As is typically the case, the church itself was free to enter. We spent about half an hour walking through.

We exited via the front of the church, which was to the west.

The church and its dome from across the street.

Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio

We started walking to the southeast to visit the Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio. This isn’t it though. The church in the background on the right here is the Basilica di San Vittore al Corpo.

This building with its castle-like tower is the Palazzo Viviani Cova, also known as the Castello Cova. It was built in the early 20th century2.

There was a bit of renovation activity going on as we approached our destination.

After walking past the construction site, we spotted a wedding in front of us. We couldn’t quite tell if it was going to start soon or if it just ended.

To the left, our destination, the Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio.

We entered the fenced in area in front of the church.

Both sides of the entrance were lined with historical artifacts. Once again we were reminded of being in Rome and Athens.

A number of extremely text-heavy signs here discuss this church. Their content is included below.

The Story

Founded by the bishop Ambrose between 379 and 386 A.D. in the area of the ad martyres cemetery outside Porta Vercellina, the ancient Basilica Martyrum - always commonly called "Ambrosian" - is universally considered the most important example of Lombard Romanesque architecture. Its current appearance is the result of a long and complex history characterized by multiple phases of construction, transformations, and restorations which have canceled almost all traces of the earliest building in which were buried the remains of the martyrs Gervasius and Protasius and, shortly thereafter, those of Ambrose, himself.

A determining role in the development of the basilica, always an object of great popular devotion and incessant pilgrimages, was played by Milanese archbishops among whom were Angilberto II (824-859) who commissioned the golden altar to house the sacred relics, Ansperto (869-881) who commissioned the atrium with portico in front of the main entrance, Federico Borromeo (1595-1631) who undertook structural consolidations and the baroque decorations of the presbytery, and Benedetto Erba Odescalchi (1712-1736) to whom the transformation of the ancient crypt is owed.

Ever since the VIII century, the Ambrosian building has been an important part of a larger architectural complex which housed - not always peacefully - two religious communities for more than a thousand years. These two communities, the monks and the canons, whose memories are still alive in the two bell towers positioned defensively on the façade of the church, divided the performance of the liturgical offices, and the care and administration of the ecclesiastical properties and goods. On the left side of the church was the rectory and the living quarters of the regular canons. On the right side of the church, the Benedictine monastery spread since 784; its Renaissance cloisters were incorporated into the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart. In 1497, the Benedictines were substituted by the Cistercians of Chiaravalle who promoted various cultural initiatives, and who opened the impressive monastic library to the public. The Cistercians remained in charge of the monastery until 1799 when the Cisalpine Republic (created in 1797 in northern Italy by Napoleon) decreed the suppression of the monastery, and installed a military hospital in its place.

The basilica of Sant'Ambrogio which houses very unusual and precious art objects, such as the Late Antique Roman sarcophagus called "of Stilicone," the golden altar by Wolvinius, the stucco ciborium of the IX-X centuries, and the sculpted wood choir stalls, owes its universal fame also to the great artists who worked there, and who have left precious records of themselves in the walls, decorations, and liturgical objects. Among these artists was Donato Bramante, the famous architect from Urbino who was active in Milan during the reign of the Sforza dukes before going to Rome. To Bramante was entrusted the task in 1492 of designing the new rectory, of reconstructing the monastery, and of fixing up the chapels in the church. Other painters, such as Bergognone, Bernardino Luini, Gaudenzio Ferrari, Legnanino, Filippo Abbiati, Carlo Francesco Nuvolone, Francesco Cairo, and Giambattista Tiepolo were responsible for the extraordinary frescoes, the paintings on canvas, and the altarpieces still preserved inside the church.

The Architecture

The earliest Ambrosian structure, built in the IV century, must have been a basilican plan divided into three naves (separated one from another by two rows of thirteen columns), and delimited by a single apse. As was typical for Early Christian and Carolingian churches, a terracotta roof probably was held up by open cross beams, and the upper walls of the central nave probably were smooth, creating an effect of continuous space because no decorative columns extending from the floor up to the roof were applied to the supporting piers.

The current apsidal area derives from changes dating to the end of the IX and the beginning of the X centuries when the main apse was reconstructed, the lateral smaller apses were erected, the crypt was added, and the floor level was raised. The mosaics which, since the Carolingian period, covered the half dome of the apse were largely redone in the XIII century, and restored many times since then.

The period between the end of the XI and the first half of the XII centuries saw the construction of the greater part of the basilica in its Romanesque form which still characterizes it even today. The three naves - completely redone with a small variation in the orientation of the axis of the building, as well as in the rhythm of the supports - are defined by the regular alternation between large and small piers connected by ample semi-circular arches supported by elegant capitals decorated with animal, vegetable, and ribbon motifs. As typical in Romanesque architecture, the space of the central nave was divided into bays by the replacement of the flammable timber roof supports with quadripartite ribbed vaults in stone, and by the addition of decorative columns extending from floor to ceiling which were attached to the supporting piers. To each of these bays in the central nave corresponded two analogous spaces in the lateral naves. The galleries were over the lateral naves, and also functioned as counterweights. The level of internal light, filtered by the large window in the façade and the three large windows in the apse, was calculated wisely.

Between the XIV and the XVI centuries, chapels were opened along the lateral naves, and the ancient chapel of S. Victor in Ciel d'Oro, with its precious mosaics dating to the V century, was incorporated into the basilica. During the course of the XVII and XVIII centuries, new renovations took place, above all of the pictorial decoration of the chapels, the stucco in the presbytery, and the transformation of the oratory of the crypt. The history of the basilica of Sant'Ambrogio has been characterized also by important restoration work, such as that conducted in the second half of the XIX century by Monsignor Rossi, and the two campaigns guided by Ferdinando Reggiori, before and after World War II.

On the outside, the Romanesque gable façade has a five-bay narthex over which is a loggia with arches whose height decreases as they are farther from the center. This façade also is flanked by two bell towers called, on the right, "of the monks" dating to the IX century, and, on the left, "of the Canons" begun in 1128, and finished only in 1889. The current door in cypress wood, composed of pieces dating from various epochs, and restored in 1750, replaces the original Early Christian door (IV century) of which remain two wooden panels, precious relics of the time of S. Ambrose.

The entrance into the church itself is preceded and protected by an ample and scenographic atrium with a portico known as the "atrium of Ansperto" from the name of the bishop who, at the end of the IX century, caused an enclosed space to be built in front of the church's façade in order to accommodate pilgrims. The current atrium, however, dates to the Romanesque period of reconstruction after the completion of the façade (first half of the XII century). Fragments of sarcophagi, inscriptions, and sculptures from the area of the basilica and from the XIX century replacement of the pavement have been reused and cared for in the atrium.

Restoration of the atrium of Ansperto by the Region of Lombardy, 1997-2000

Traces of the Paleo-Christian Church

From 379 onwards, Bishop Ambrose encouraged the construction of the Basilica, destined to be the place of his tomb; however, the finding of the remains of Gervase and Protase, Milanese Martyrs of the noble Valerii family, in an area of the necropolis in 386, a period during which relations between the Bishop and Emperor were particularly difficult, convinced Ambrose to dedicate it to the two Saints. The building thus took the name of basilica Martyrum (of the Martyrs) and in fact, was solemnly consecrated in 386. The only remaining part of the Ambrosian structure is the floor plan of three naves, divided by thirteen columns on either side, while all the rest was added during the following centuries.

Hidden Treasures

A few highly significant items of a remarkable artistic level which testify to the Paleo-Christian phase of the building are housed in the Basilica. A massive sarcophagus, made of Carrara marble in the years 385-390 and decorated with scenes from the Old and New Testaments, can be seen beneath the Romanesque ambo. Known as the "sarcophagus of Stilicone", from the name of the Vandal general of the armies of Emperors Theodosius and Honorius (end 4th-beginning 5th cent.), it can be traced to a person of high rank, perhaps a court official in the train of the emperors who, from the end of the 3rd century until 402, often resided in Milan.

Two fragments of a marble screen from the Ambrosian Age and several polychrome wall inlays dating from the 6th century are part of the Treasury of the Basilica.

Ambrose, a protagonist of 4th century Milan

Ambrose was one of the most important figures of the Western Church, a protagonist of his epoch and a man of faith and action admired by his contemporaries and by posterity.

He came to Milan as governor with the title of consularis Aemiliae et Liguriae, but, at the death of the Arian Bishop Auxentius, was nominated Bishop by popular acclamation: he was ordained Bishop in 374, on the 7th December, a day on which Milan still pays homage to her Patron Saint.

Until his death in 397, inspired by faith and sustained by a very Roman sense of duty, he did his utmost for the Church and the faithful, fighting against paganism and heresy, especially Arianism and resisting the interference of the civil authorities in ecclesiastic matters, even against Imperial power.

To the faithful he left theological and doctrinal tracts, orations and epistles and, to the Milanese, great churches to pray in and pay homage to the relics of Martyrs and Saints.

The Chapel of San Vittore in Ciel d’Oro

According to a medieval tradition, the chapel was chosen by Bishop Ambrose to house the tomb of his brother Satirus, who had died in 378, as it was near the relics of the Martyr, Victor. The small building, with a trapezoidal floor plan, apse and crypt was originally separate from the basilica Martyrum (later Sant'Ambrogio). The precious mosaics, some of the few still existing in the city, are an extraordinary testimony of this flourishing art, widespread in the Milan of the 5th century but lost over the centuries.

There was a sign that indicated the church was closed for a private function, possibly the wedding? But, we saw other tourists going in the other door. So, we did too.

The entrance area of the chapel, once dedicated to the Holy Sacrament, was completely repainted in 1737-38. The "Holy Allegory" on the lefthand wall, and the "Glory of the Angels" on the vault were painted by Pietro Maggi (ca. 1660-before 1738). The altarpiece by Andrea Lanzani (ca. 1641-1712) is called "The Last Communion of S. Ambrose."

The chapel, a precious and rare example surviving from the Early Christian period in Milan, was commissioned by bishop Materno for the remains of the martyr Victor. It was constructed in the IV century, before the Ambrosian basilica. According to tradition, it is here that Ambrose buried the body of his brother, Satiro, around 375 A.D.

Thè chapel, by then transformed into a little basilica dedicated to S. Satiro, remained isolated for various centuries. It was included in the complex of the basilica only in the XV century. The current state of the chapel is due to the restorations of the XIX century, and to the reconstruction work after the serious damage caused by bombs in World War II. The last intervention in the mosaics dates to 1981-1989.

The importance and fame of this chamber derive from the splendid mosaic decoration, dating to the V century, in which is found the oldest known representation of bishop Ambrose whose face is depicted with astounding realism. At the center of the cupola, completely covered with golden tesserae (creating a golden heaven, that is, a ciel d'oro), is the bust of S. Victor on whose head rests the gemmed crown of martyrs. On the walls, bishops and martyrs are depicted: on the viewer's left, Ambrose between Gervasius and Protasius, on the viewer's right, Materno between Nabore and Felice. The altar frontal is a marble balustrade, dating to the IX century, carved with a woven effect. It came from the basilica.

In the crypt of the chapel, built beginning in the IX century, a Roman pagan sarcophagus from the end of the lII century is preserved over the altar. It belonged to a centurion, and later was reused for a Christian burial.

Various reliquaries enclose bones from the area of the nearby late antique

cemetery, and fragments of inscribed slabs, such as the IV century funereal epigraph of Manlia Daedalia, a companion of Ambrose's sister, Marcellina.

Restoration by the Region of Lombardy, 1987

Christian soldiers Nabor and Felix, originally from Mauritania, were arrested in Milan around the year 303 along with their comrade Victor during the persecution by Emperor Maximian. They were sentenced to decapitation, which was carried out at Laus Pompeia (now Lodivecchio).

In 1799, their remains - originally brought back and buried in Milan by a matron named Savina in the 4th century - were transferred from the Church of San Francesco Grande to the Basilica. The earliest documented mention of Nabor and Felix comes from the sacred hymn Victor, Nabor, Felix pii, which Ambrose wrote in honour of these three "foreign martyrs". They became soldiers of Christ by rejecting worldly weapons in favour of the shield of faith. Ultimately, they chose to sacrifice their lives to attain the certainty of eternal life.

The large crypt was built in the second half of the 10th century during the construction work in the apse area of the basilica. The current state is due to the interventions undertaken in the 18th century, which were promoted by cardinal Benedetto Erba Odescalchi, and to work in the 19th century following the replacement of the bodies of SS. Ambrose, Gervasius and Protasius. The holy relics are contained in a silver urn (created by Giovanni Lomazzi in 1897 following designs by Ippolito Marchetti) placed below the golden altar.

S. Ambrose's body is in the middle, dressed in white pontifical robes, while the two martyrs Gervasius and Protasius wear white and gold surplices, red dalmatics, golden crowns with palm branches, symbols of martyrdom. Originally, the martyrs Gervasius and Protasius lay in the nearby chapel of SS. Nabore and Felice (later called the church of S. Francesco Grande, demolished in the 18th century) in the area of the cemeten ad martyres. In 386, Ambrose himself disinterred their remains and solemnly buried them under the altar of his basilica in the tomb lined with precious marbles which he had prepared for himself. When he died in 397, the bishop was buried in another tomb alongside the two martyrs. In the 9th century, archbishop Angilberto Il located and identified the relics, and translated them into a single porphyry sarcophagus which was placed, on a different axis, over the two previous, then empty, tombs. The same sarcophagus was brought to light in 1864 during deep excavations around the high altar. It was opened in 1871, on August 8th. An inscribed tablet set into the floor of the crypt also reminds the original place where S. Marcellina, Ambrose's sister, was buried. Her remains, identified in 1722, were translated to a chapel in the right aisle.

This is a plinth, or base, of one of the twenty-six columns (thirteen to a side) which delimited the central nave in the original basilica dating to the Ambrosian period (end of the IV century).

It was discovered during excavations in the XIX century.

According to popular tradition, the bronze serpent which Moses caused to be made in the desert sits atop this granite column - perhaps belonging to the IV century - from the original basilica. In reality, the serpent probably is of Byzantine origin, and was put on the top of the column perhaps in the XI century.

In the same period, opposite the serpent on the other side of the nave, a bronze cross had been placed on a granite column, thereby creating a symbolic comparision, however, the current column and cross date to the XIX century restoration.

We spent about 25 minutes in the church before heading out.

A few additional artifacts on the walls outside.

The entrance to the church is pretty non-descript.

We headed down to the Sant’Ambrogio Metro station which is near the church’s entrance.

We noticed what looks like a bar code on the side of one of the brick walls by the station entrance. What is this? A post on Reddit indicates that it is used to check for building movement around excavation projects. There should be a marker on the ground somewhere nearby which indicates a reference point for measurements.

The Castello Cova, as seen by the Metro station entrance below street level.

There is a gate between these two brick towers, the Pusterla di Sant’Ambrogio (Postern of Saint Ambrose).

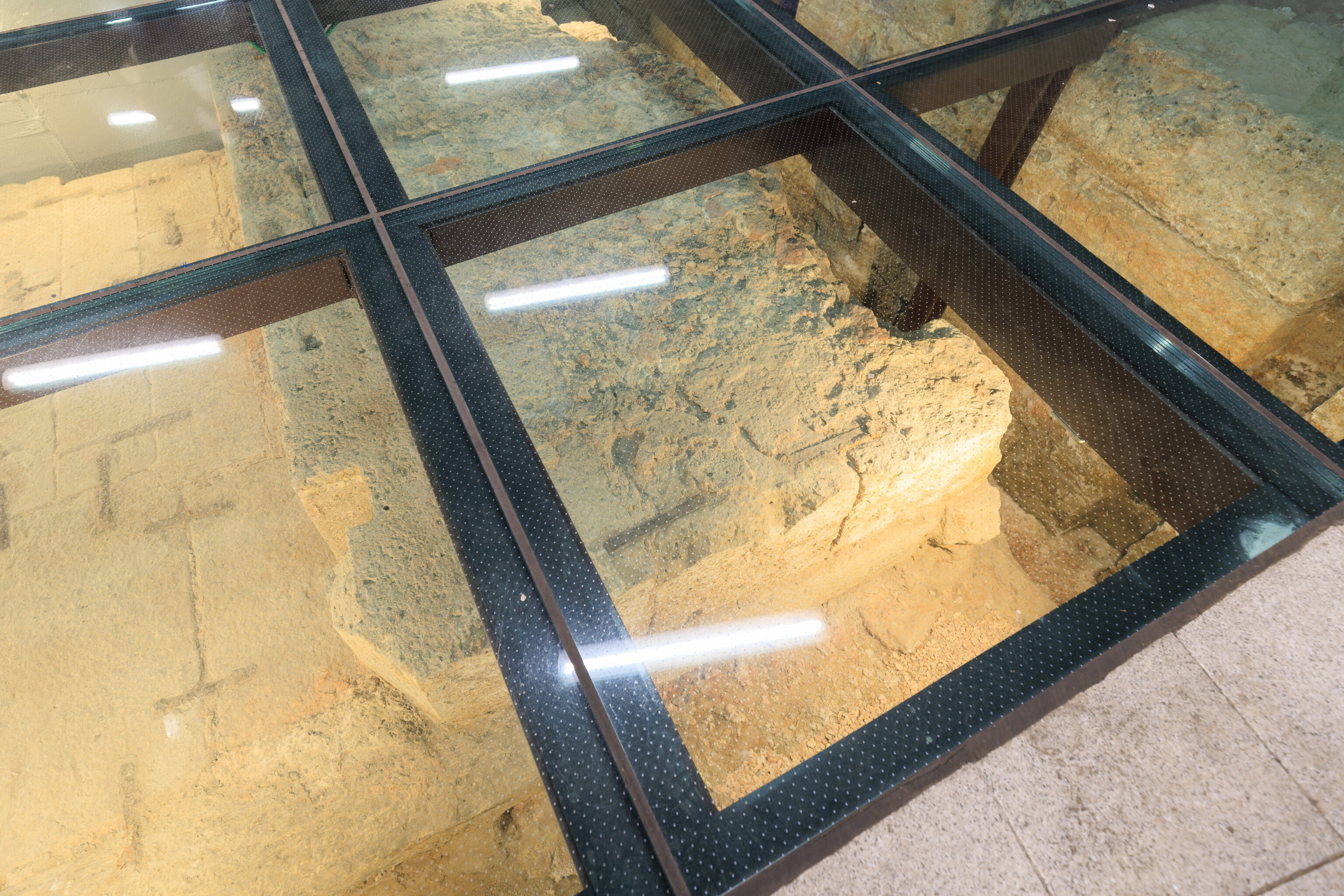

There is an archeological site here below the floor of the Metro entrance. Two signs describe what is here.

The Canal and the Postern of Sant’Ambrogio

During the construction of the connecting corridor between metro lines 2 and 4, a section of the quayside of the Inner Circle of the Navigli canals came to light. It is located in front of the Pusterla di S. Ambrogio, one of the fortified accesses to the city along the medieval wall.

The masonry preserved here, once overlooking the canal, presents a coating of Lombardy limestone blocks. On these can be recognized holes for fixing with metal elements, along with different working techniques and dimensions due to their recovery from older structures.

Some elements have a rustic ashlar finish, typical of the Lombardy area in the medieval age, to which the construction of this quayside also dates back (14th century). The two vertical grooves visible on the structure were probably used to house wooden bulkheads for regulating the flow of water in the canal.

The southern portion of the wall, visible for a total length of over 30 meters, was subsequently rebuilt, maintaining the stone base and building the upper part with bricks. At the foot of the masonry there were 32 wooden poles driven into the natural layer of gravel and sand.

With the closing of this section of the Inner Circle at the end of the 19th century, the quayside was partially demolished and the bed of the Roggia Castello was built over it, into which the waters coming from the Castle were channeled.

Inside the canal, next to the quayside, the base of a ravelin is preserved, a masonry body in front of the gate, founded in the bed and probably used to support a bridge crossing the canal. It is composed of a bottom part covered with stone slabs bound together by iron cramps and the base of a turret, built close to the quayside.

Despite the limited spaces and the numerous constraints of the area, including the presence of the underlying tunnel of Line 2, it was possible to create the necessary space within the passage to preserve and enhance the monumental masonry found, visible through the transparent floor.

Milan’s Medieval Walls and the Postern of Sant’Ambrogio

"The main gates of the city, well-equipped, were six in number; ten were secondary, called pusterle (posterns), all built on very solid foundations. Each of the main gates had two towers, although unfinished, also based on very strong foundations."

This is how Bonvesin de la Riva described in the 13th century the walls that protected the city, built after the destruction caused by the emperor Frederick I in 1157-58, following the moat, dug before the siege to protect not only the old core of the city but also the boroughs that had developed outside the Roman-era walls.

After the end of hostilities in 1167, the restoration of the moat and the adjacent vallum began, a series of embankments on the side towards the city (the so-called "terraggi") and in 1171 the Municipality began the construction of stone gates and towers; the completion of the wall circuit was only completed with the government of Azzone Visconti (1328-1339).

The Pusterla di Sant'Ambrogio is framed by two towers and is the only one to have a double opening. Its current appearance is due to the restoration work directed by Gino Chierici in 1936-39, which saved the surviving structures from urban transformations, freeing them from subsequent superimpositions. Over time, in fact, the Pusterla lost its original defensive function and was reused and adapted for private dwellings. What remained in place were: the South-West tower for its entire height, part of the two arches and the stone base of the North-East tower (which is now the lowest).

On the occasion of the restoration and excavations carried out around the monument, the attachment points to the walls were also identified, as well as the traces of a secondary moat around the Pusterla and the bridges that allowed it to be crossed. According to some scholars, these elements could also suggest the presence of a 'ravelin', an outwork of the Pusterla formed by two towers equipped with drawbridges that allowed the crossing of the main moat towards via San Vittore.

This hypothesis, which at the time was not supported by concrete evidence, now finds confirmation in the structures found during the construction of the connecting corridor between Sant'Ambrogio M2-M4 stations and preserved here. Moreover, the exit from the station at the foot of the Pusterla allows an unprecedented view of the towers and the basilica of Sant'Ambrogio, which gradually appears while walking up the staircase on which the lines of the old defensive system can also be seen.

Excelsior Hotel Gallia, a Luxury Collection Hotel

We took the Metro back to Milano Centrale to finally check into our room at the Excelsior Hotel Gallia.

The hotel is part of The Luxury Collection, which is part of Marriott. As Titanium members of Marriott’s Bonvoy program, we received a room upgrade. Breakfast is also included as a result of our Bonvoy status.

The doors to the rooms are quite unusual!

The room was a good size with two windows and desk space along one of the side walls.

The bathroom was large with a nice tub and shower.

These paper water cartons seem pretty popular with hotels in Europe. We kept this one because it it had some nice hotel branding and was made in Italy. This does seem like a rather wasteful way to provide water though, though perhaps it is better than plastic.

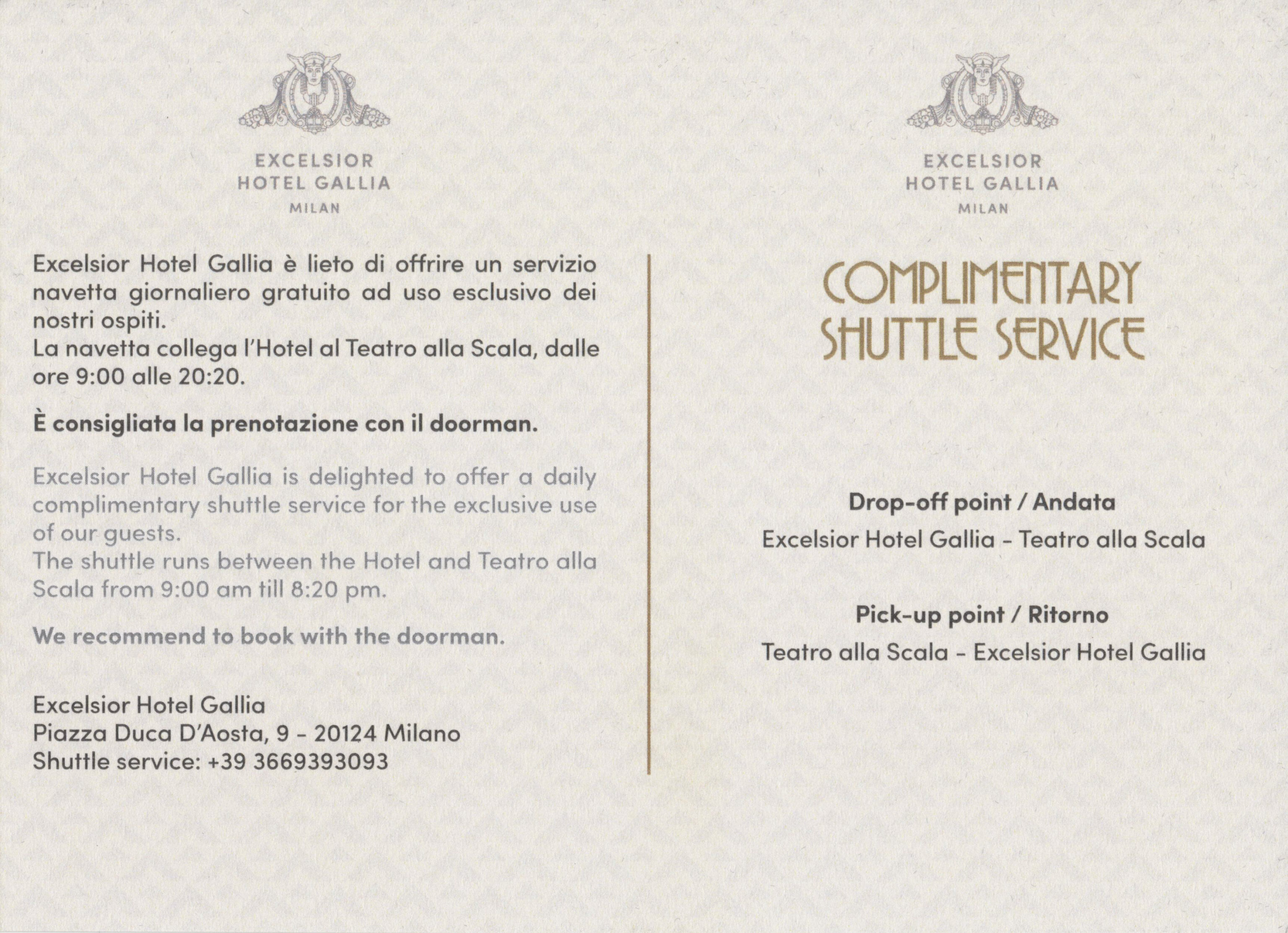

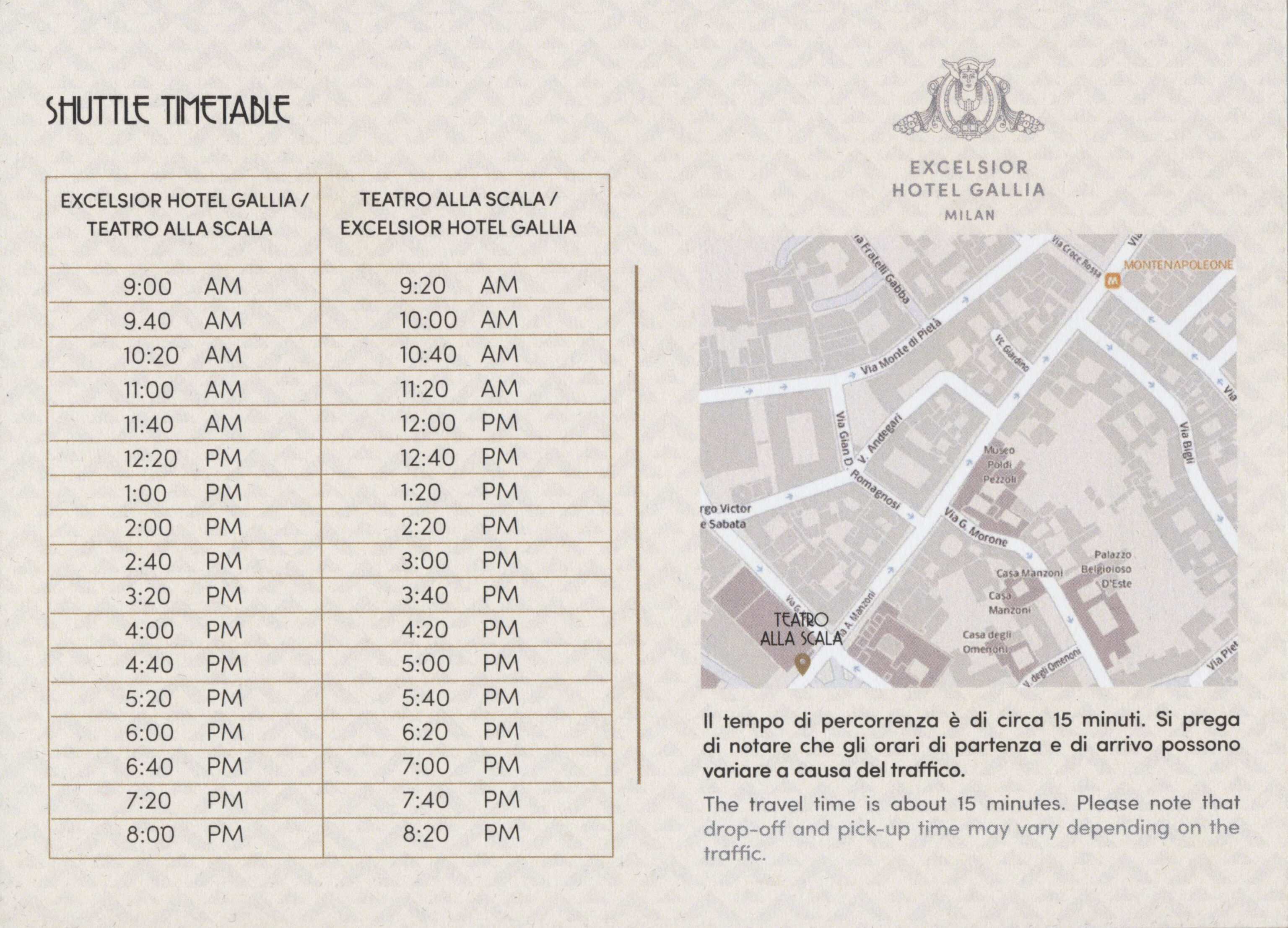

The hotel offers a complimentary shuttle to the Teatro alla Scala, a theatre by the Leonardo da Vinci statue that we saw earlier today by the north entrance to the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II.

Our room’s two windows actually both have tiny balconies. There is just enough room to stand outside and enjoy the view. Our room is on the northeast part of the hotel and overlooks a piazza on the west side of Milano Centrale.

Evening chocolates were provided, likely part of turndown service which likely happened before we checked in as it is around 4:30pm right now.

We took a look at various decorative elements of Milano Centrale using our telephoto lens.

We decided to head out to the station to find something quick to eat. We ended up visiting the Mercato Centrale Milano on the west side of the station. This is basically a long and narrow two floor food hall. While there were many food options, it does seem they mostly involve heating food that has already been prepared in advance. Nothing seemed particularly compelling. We ended up just getting some chicken.

After dinner, we walked through the station to the east side where we got gelato from Antica Gelateria Sartori. This small stand doesn’t look like much but it has been here since 1945, with the original business established in 1937, and was pretty good!

A night time view of Milano Centrale from one of our balconies after we returned to the room.

- La Mela Reintegrata or The Apple Made Whole Again (Milan, Italy, 2015-present)

The Big Apple

https://barrypopik.com/blog/la_mela_reintegrata ↩︎ - Palazzo Cova

LombardiaBeniCulturali

https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/architetture/schede/1j590-00011/ ↩︎

One Reply to “Milan’s Historic Center”