After waking up at the Grand Bretagne, we had breakfast in the rooftop restaurant before heading out to visit the Acropolis. We spent most of the day walking around this historic hill and saw the Parthenon up close. After, we visited two churches before having dinner and returning to the hotel.

Morning

After waking up at the Grande Bretagne, we went upstairs for breakfast. Breakfast begins at 6:30am and is served at the GB Roof Garden. As the name suggests, it is on the top floor of the hotel. Although we typically try to have breakfast at opening time when we’re traveling, we didn’t want to go that early today as we have timed entry tickets for the Acropolis at 11am. With an 11am entry time, we wanted to delay breakfast to ensure we were as full as possible for the day as we likely would not be able to eat until late in the afternoon.

The restaurant’s rooftop location provides a fantastic view of the Acropolis and the Parthenon atop it.

It is also possible to see the Old Royal Palace from the restaurant.

As Titanium members of the Marriott Bonvoy program, we receive complimentary breakfast as an option at Luxury Collection hotels. Breakfast here is buffet style as well as with dishes that can be ordered off of the menu. Everything was included for us. Some of the menu items are actually available at the buffet.

The buffet had many typical western items such as eggs and bacon. We also picked up some Greek specialties. We particularly liked the Koulouri, which we felt was very similar to a Montreal style bagel, except larger. Doing a bit of research, it is the Greek variation of simit, which is common in areas of the former Ottoman Empire, which included Greece.

We ordered a waffle with fruit from the menu. A pretty simple dish.

We also ordered an omelette. We had more which we unfortunately didn’t photograph. Overall, it was a decent breakfast with a variety of items, though not the best we’ve had.

Acropolis

After heading out, we went down into the Syntagma Metro station via a stairway by the southeast corner of the hotel. We took Line 2 (Red) one stop to the Akropoli Metro station.

As we were exiting the station, we noticed these sculptures. The are replicas of sculptures from the east side of the Parthenon.

A sign describes these replicas:

Sculptures from the east pediment of the Parthenon

The sculptural decoration of the Parthenon consists of three units, the metopes, the frieze and the pediments, and is the work of Pheidias and his pupils. The pediment sculptures (438-432 BC) are compositions of figures of supernatural size, isolated or in groups, cut in the round from Pentelic marble. According to the 2nd century AD traveller Pausanias, the theme of the east pediment was the birth of the goddess Athena, and of the west pediment the fight between Athena and Poseidon over the protection of Attica.

The figures at the centre of the east pediment have not survived. They would have been the main participants in the event of Athena's birth from the head of Zeus, i.e. Zeus, Hera and Athena herself, surrounded by the other Olympian gods. The chariots of Helios (sun) and Selene (moon) occupied the two corners of the pediment, delineating the time-span of the event.

The casts that are exhibited here are from the original sculptures that decorated the left side of the pediment. Depicted from left to right are: Helios, and the heads of the four horses of his chariot, as he rises from the waves of Oceanos (ocean); opposite him, Dionysos, half-lying on a rock which is covered by his garment and the panther skin he usually wears. Then follow two seated goddesses, Demeter and Kore, and a standing figure (Hebe or Artemis) who moves towards them, announcing the event.

The central group, with the birth of the goddess, was lost when the Parthenon was converted into a Christian church (5th cent. AD). Modern reconstructions have been based on fragments of torsos found on the Acropolis and in accordance with other representations of the same subject. The sculptures that remained in their original position on the building were sketched by J. Carrey (1674). They were almost entirely removed by Lord Elgin from 1801 onwards and, since 1816 they are in the British Museum, where they are exhibited. Now, the two inside horses from the chariots of both Helios and Selene, as well as the torso of Selene, are in the Acropolis Museum.

We walked out of the station at around 10:30am and found the Acropolis pretty quickly!

We ended up needing to wait in a queue for a bit as they were adhering to the ticketed entrance times. Each time slot is a one hour window to enter, so for example, our slot was from 11am until 12 noon. It was rather hot under the morning sun, particularly as there wasn’t any shade. We were glad we arrived early as the queue behind us ended up being pretty long.

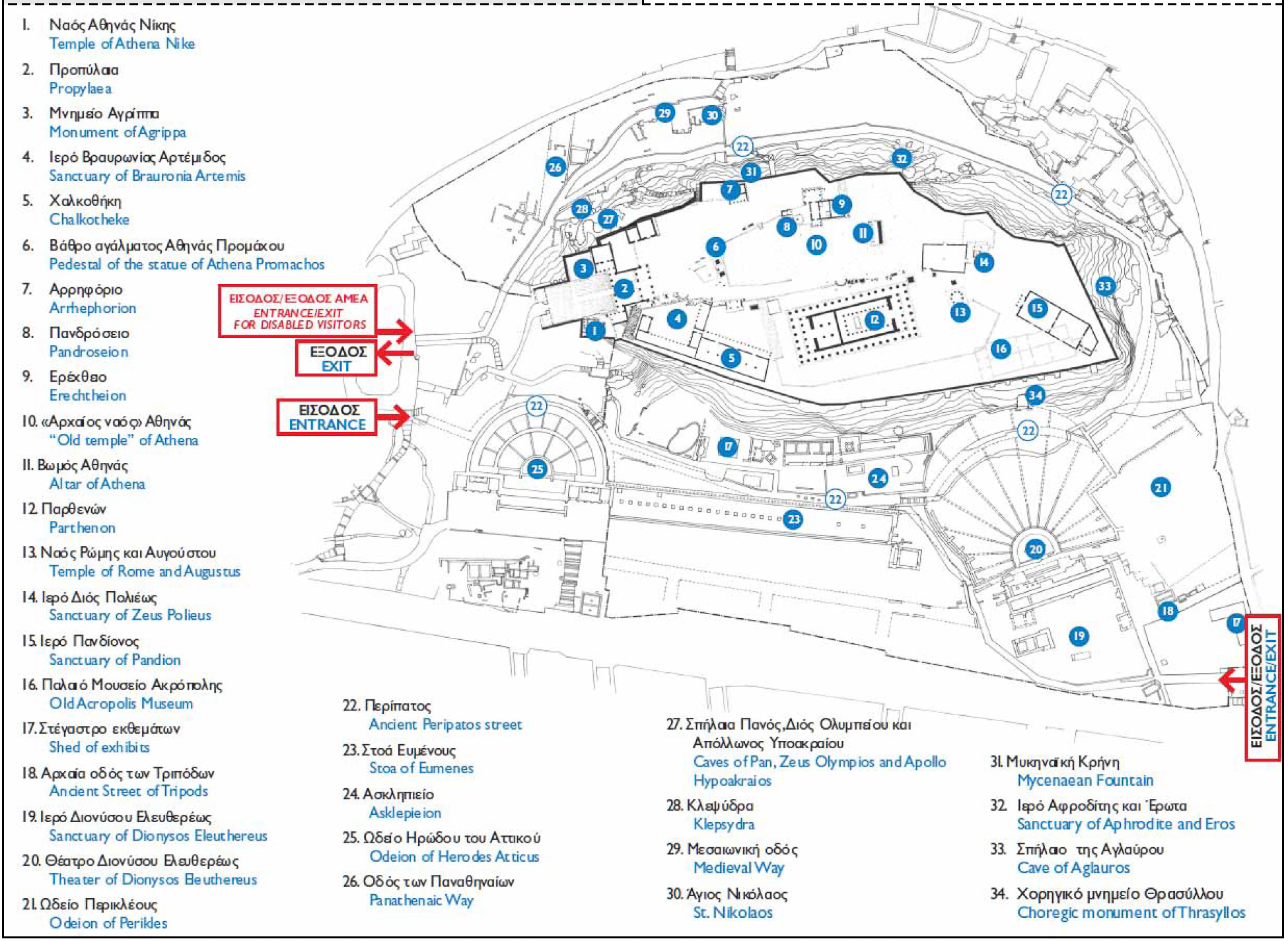

The only map we had was the one from our tickets in PDF format. After entering, we decided to circle around the site counter-clockwise, starting with the area at the bottom left side of this map, which happily corresponds to southeast.

Much of the Acropolis has been built up to resemble a huge fortress.

We found a sign with a map by the entrance.

The English text on this sign reads:

The Slopes of the Acropolis have been inhabited from prehistoric times on, mainly because of the existence of springs. During archaic and classical times this area became an intellectual, cultural and religious center of major importance for life in ancient Athens.

In the 6th cent. B.C. the Sanctuary of Dionysos Eleuthereus was founded on the South Slope. The theatre of the same name was also established at that time, and it was here that the ancient Greek drama was born and flourished. Further development during the 5th cent. B.C. included the construction of the Odeion of Perikles, where musical contests were held, and of the Sanctuary of Asklepios, the first shrine of that god in Athens. During the 4th cent. B.C., as part of the building program of the archon Lykourgos, the sanctuary and the Theatre of Dionysos were totally reorganized, while a great number of choregic monuments were erected at that period. Later additions, the Stoa of king Eumenes II of Pergamon (2nd cent. B.C.) and the Odeum of Herodes Atticus (2nd cent. A.D.) continued the cultural and intellectual tradition of the area into the Roman era.

The East and North Slopes also had important roles in the religious life of the city. This is indicated by the existence of the "sanctuary of Aglauros" Cave, the Sacred Caves, the Shrine of Aphrodite and Eros, the final section of the Panathenaic Way, as well as of springs (the Mycenaean Fountain and the Klepsydra), which were often associated with cults and rituals that took place on the Sacred Rock.

The urban web of ancient Athens encompassed the hill of the Acropolis and its Slopes through main roads, such as the street of the Tripods. The hill is also connected with the sanctuary of the Olympian Zeus and the southern suburbs of the ancient city of Athens through similar arteries. The road known in antiquity as the "Peripatos", which went around the Slopes of the Acropolis, is mentioned in an inscription of the 4th cent. B.C. that was carved on a rock on the North Slope.

From late antiquity up to the Turkish occupation, the area developed a religious (churches of St. Paraskevi and St. Nikolaos) and intensely residential character.

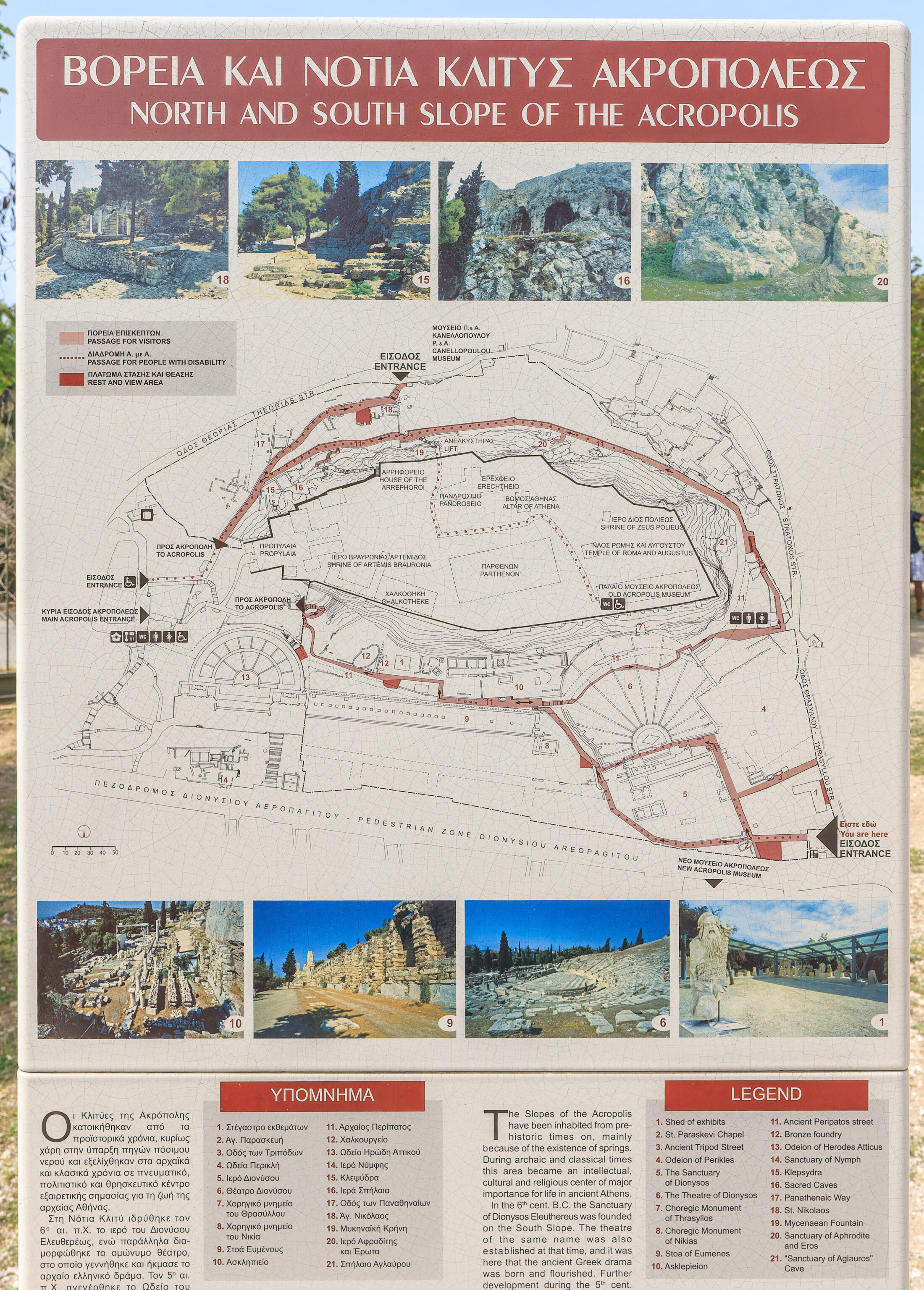

We also saw this sign which lists some of the fauna that can be found in the area. It mostly listed various birds, some of which are familiar to us from home like the Barn Swallow, Rock Pigeon, and House Sparrow, which is an invasive species in the US.

The sign also lists a tortoise species. We actually saw one here near the entrance trying to walk under the fence with some difficulty.

There were some sculptures under a protective canopy near the entrance. We took a look at them first.

There are ruins of a number of structures near the entrance. None of them are particularly obvious.

A sign describes this area:

Three ancient roads (1,3,7) meet outside the southeast corner of the Sanctuary of Dionysos. The first road (I) connected Olympieion with the South Slope of the Acropolis and the Sacred Rock. The second (3), oriented in southeast-northwest direction, came from the south fringes of the city and ended up at the east entrance (parodos) of the Theater of Dionysos. In its course along the east precinct wall of the Sanctuary of Dionysos, it joined the end of the Street of the Tripods (6) in front of the propylon of the Sanctuary of Dionysos. The third road (7), from a southwest direction, probably crossed the other two outside the southeast corner of the Sanctuary of Dionysos, where the remnants of a small roadside shrine (8) of the first half of the 5th c. BC, made of porous stone, have been revealed. It was dedicated to an unknown deity, perhaps Hecate or Hermes.

South of the precinct wall and the roadside shrine, the ruins of a single-nave church, dedicated to St. Paraskevi (9), have been found. Its floor was composed of ancient marble spoils and remains of wall paintings were still preserved on its side walls. The basilica, which appears for the first time on a plan by the Venetian engineer Verneda, in 1687, had three building phases from the late Byzantine times to 1860. It had probably suffered extensive damages during the siege of the Acropolis in 1827. In its place a small chapel was built, around 1860, as a remembrance of the earlier building phases. Today, the remnants of the second phase of the 17th century are preserved.

The church mentioned in the sign, St. Paraskevi, seems to have been here.

We could either go north or west from the entrance. We decided to go west. This area here contained the Later Temple of Dionysos Eleutherus.

A sign describes this temple and its remnants:

The Later Temple of Dionysos was built a few meters south of the Archaic Temple of Dionysos (dating to the 6th cent. B.C.), and it seems that for a period of time the two temples coexisted and were in use simultaneously.

The temple was initially dated to the 5th cent.B.C., based on the testimony of the 2nd cent. A.D. traveller Pausanias that it housed the chryselephantine statue of the god Dionysos, a work of the sculptor Alkamenes. However, the results of recent research in the 1960s indicate that the temple is more likely to be dated to the second half of the 4th cent. B.C., during the archonship of the orator Lykourgos at Athens. During that period, both the Sanctuary and the Theatre of Dionysos were fully developed. According to most scholars, the temple was Doric, with four columns in front and one on the side walls of the "pronaos", the eastern part of which is probably a later addition.

However, certain fragments of lonic cornices that have been attributed to the Later Temple, have raised some doubts concerning its original architectural order.

Today, only the conglomerate foundations of its walls - the pronaos on the east and the cella on the west - and the statue's base are preserved from the Later Temple of Dionysos. The exterior wall foundations measure 21.95×9.30 m. and are made of conglomerate stone, the "arouraios" stone known from ancient inscriptions. This material, which was used in most of the buildings of Athens in the late 5th and 4th centuries B.C., is very durable if kept covered, but when exposed to air and variable weather conditions it becomes friable and quickly deteriorates.

In common with the other monuments in the Sanctuary, the Later Temple of Dionysos was revealed and investigated by the Greek Archaeological Society and the German Archaeological Institute in the second half of the 19th cent., during the excavation of the Theatre that extends to its north. During the years 1960-1962 the First Archaeological District carried out some cleaning, arrangements and supplementary research inside the Sanctuary.

In order to protect the remnants of the monument, which have already suffered significant damage, and to improve their readability, they were partially filled with earth in 2009 on the basis of a study approved by the Central Archaeological Council. The surviving upper surface of the ancient foundation has been left visible for teaching purposes. As part of that operation, some fallen blocks of stone were also repositioned in their original location, and missing parts of the monument's foundation were indicated with additions made of mortar.

There was a wall, the Wall of Haseki, here along the modern day path. It was part of Athens’ city wall built by the Ottomans in the late 18th century.

Just a little bit to the north, a sign describes this area as containing the Archaic Temple of Dionysos Eleuthereus.

The sign reads:

The Old or Archaic Temple of Dionysos was erected on the South Slope of the Acropolis in the mid-6th cent. B.C., during the era when Peisistratos or his sons ruled Athens. The cult of Dionysos was introduced to Athens from the deme of Eleutherae, which was originally Boeotian and later belonged to Attica. The Archaic temple, which must have been in operation until at least the era of the traveller Pausanias in the 2nd cent. A.D., was built to house the "xoanon", i.e. the wooden cult statue of the god, which the priest Pegasos transferred from Eleutherae.

The temple was Doric; as concerns its type, most scholars believe that it was distyle "in antis" on its eastern façade, although some believe that it had a four-column porch. The temple's overall dimensions are estimated to have been about 13.50 X 8.00 m.

Only parts of the foundation and crepis of the northern and western walls of the temple, which is in the northwestern part of the Sanctuary, are preserved today. More specifically, the foundations, euthynteria, and first course of the crepis in the northernmost section of the west wall, the north wall of the cella, and the northernmost section of the transverse wall between the pronaos and cella are preserved. The lower foundation courses and euthynteria are of limestone from the Acropolis; the crepis is of limestone from Kara (Kareas).

During the excavations carried out at the site of the Theatre and Sanctuary of Dionysos by the German Archaeological Institute under the direction of W. Dörpfeld, between 1882 and 1895, a number of architectural members of porous stone were uncovered in front of the temple that came from the superstructure of a Doric building; according to the excavator, these matched the monument in size and form. A fragment of a porous relief tympanon of a pediment depicting two Satyrs and a Maenad dancing had previously been found near the temple and attributed to it. This relief is now on exhibit in the National Archaeological Museum. More recently, during the 1960s and 1980s, additional architectural members were identified at the site as coming from the temple. Most of these have been placed near the remains of the monument.

At the same time the temple was erected, some sort of terrace supported by a semi-circular retaining wall must have been created to its north, where the rituals in honour of Dionysos would have been celebrated during the Great or "City" Dionysia. Viewers would have observed these rituals from the slope of the hill, which at that point assumed a simple semi-circular configuration.

The construction of the Stoa just north of the Archaic Temple of Dionysos at a restricted area between the temple and the orchestra of the theatre at a later date, most probably in the second half of the 4th cent. B.C. (a period during which the Sanctuary grew and was reshaped with the construction of new buildings), led to a series of requisite construction solutions at the point of contact between the two buildings at the southwest corner of the Stoa. Characteristically, the two marble stones of the first course of the Stoa's crepis lay in part on the euthynteria of the Archaic Temple of Dionysos.

The stoa mentioned on the sign was here. It is identified here as the Doric Stoa, although there seems to be another stoa that is described as the Doric Stoa further north. So, this might mean this is a Doric-styled stora rather than it being the Doric Stoa.

Presumably the three stone pieces behind the sign were part of the stoa?

There were some really nice marble benches in the shade here which we used to rest for a bit before continuing to the north.

We walked to the north a little bit to reach the southwest corner of the Theatre of Dionysos.

A sign provides some detail about the retaining wall on the west side of the theatre, presumably what we seen in front of us here:

THE THEATRE OF DIONYSOS

The retaining wall of the Western Parodos

The existence of the oldest ascending way to the west of the Theatre, leading to the Acropolis and other sanctuaries, determined the west end of the Athenian theatre, as well as the shorter length of the western parodos (entrance) in comparison to the eastern one. This entrance was marked and closed with a monumental gate (propylon) since the construction of the theatre. At first the propylon was made of wood and later under the emperor Augustus (27 BC-14 AD) a monumental marble propylon was constructed of the same form and dimensions with that of the eastern parodos. The retaining wall of the parodos not only supports the heaped mass of earth into which the rows of stone seats were embedded but it also constitutes the south face of the auditorium, which was built entirely of stone between 350 and 320 BC, and delimitated its west entrance. Beside the entrance and mainly in front of the retaining wall bases of honorary statues and other dedicatory monuments were erected that represent the different historical phases of the theatre (from the 4th century BC until the Roman times). At a higher level, behind the retaining wall, part of the mediaeval "Rizokastro" city wall (mid-13th century) is preserved.

The pillaging of the stones of the retaining wall begun after the destructions caused by the Heruli in Athens (267 AD) and continued up to the mediaeval times. The excavation of the monument in the mid-19th century revealed the static problems of this demolished part of the theatre. The restoration, conservation and partial reconstruction of the retaining wall, took place between 2002 and 2005. Limestone, quarried today as in the past from an area in Piraeus that belongs to the Chatzikyriakos Foundation, was used, as in antiquity, for the outer part of the retaining wall. For the reconstruction of the inner part of the retaining wall, originally built of conglomerate stones, artificial stone was used, since no conglomerate quarry is in use today. For the partial reconstruction of the retaining wall 83 new limestone blocks, 37 man-made conglomerate stones and 13 reconstructions of missing parts of ancient stones were put in place. The remains of the "Rizokastro", embedded in the heaped earth of the auditorium, were also restored. The identification of the ending coping stone of the wall in the foundation of a late roman part of the theatre (Bema of Phaidros, 4th century AD) in 2005 allowed additionally the part restoration of the coping of the wall and of the inscribed base of the famous statue of the dramatic poet Astydamas (erected 340 BC) that has been incorporated with a specific complicated technical solution.

We walked to the east along the southern edge of the theatre. It seems the stage wpi;d have been here where we are standing with the orchestra in front of us and with 180 degrees of seating around it. The stage would have been part of a building that spanned the width of the theatre.

A sign describes the former stage building of the theatre:

THE THEATRE OF DIONYSOS

The stage building

Among the elements of the tripartite form of the ancient Theatre (orchestra, auditorium, stage), the stage building is the one most related to the evolution of theatrical production. During its roughly one thousand years in operation, the Theatre of Dionysos was therefore subjected to the greatest amount of alteration.

To the south of the orchestra, which held a central place in the theatrical action from the very birth of the ancient theatre. a permanent stage building was added in the 5th century BC. The development of Tragedy, in particular, by the great dramatic poets, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, necessitated the addition of a permanent stage building that could serve the theatrical performance in various ways as well as improving the acoustics of the theatre. The renovation of the wooden theatre began in the time of the great Tragedians, and especially after the mid-5th c. BC. Due to the financial problems stemming from the devastating Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), the stage building was ultimately constructed with cheaper materials, though with rich painted façade.

With the monumental rebuilding and extension of the theatre in stone in the second half of the 4th century BC (Lycurgean phase), the stage was rebuilt entirely in stone and acquired a marble façade flanked by two projecting wings with Doric colonnades (paraskenia). This first stone structure was later altered during the 2nd or 1st century BC, when it acquired a Doric colonnade along the ground floor façade and, probably, an upper storey: the two paraskenia were also shortened. These alterations were necessitated by elements of the theatrical action transferred to a raised stage (logeion).

The sociopolitical changes of the Roman period led in tum to substantial alterations to the stage building. Under the emperor Nero (61-2 AD), the two-storey stage building acquired a deep proskenion (performance level) along with rich architectural elements (scaenae frons) on its façade. Under Hadrian (117-138 AD), the philhellene emperor who was honoured as the Neos Dionysos [New Dionysos], the stage building was subject to alterations in a classicizing spirit. Its façade was adorned with monumental female statues and satyrs personifying the three genres of dramatic poetry (Tragedy, Comedy and Satyr Play).

At last period of prosperity for the Theatre, after its destruction by the Heruli (267 AD), is signified by the Bema of Phaedros (4th century AD), so called because of the surviving dedicatory inscription. This was decorated with curved marble slabs taken from the older hadrianic constructions (maybe altars) which depicted scenes from the life of Dionysos and the establishment of his worship on the South Slope of the Acropolis. The construction of the early Christian Basilica at the eastern entrance to the theatre in the 6th century AD marks the start of a new era that would bring major changes to the theatrical installation and its operation.

Between 2003 and 2005, the scattered architectural members from the stage area were processed and displayed for teaching purposes. The focus here was on grouping the surviving architectural members from the monument's Hellenistic and Roman phase and repositioning them for illustrative purposes. The inside of the building also received a new clear soil fill. These were the first steps in the further study of the monument and the display of its stage building, which will include the partial restoration and reintegration of remaining architectural material.

A closer look at what remains of the theatre’s seating.

These columns and other stone pieces are on the south side of the path that runs in front of the theatre. They could be parts of the theatre stage building, or the temples that were here as well?

We walked a few more steps to the east where we had a clear view of the seating and orchestra area of the theatre.

A sign describes the seating, referred to as the auditorium:

THE AUDITORIUM OF THE THEATRE OF DIONYSOS

The Theatre of Dionysos is the largest monument on the southern slope of the Acropolis, although the preserved remains of its seating portion, namely the auditorium or cavea (koilon), represent only a small portion of the gigantic original complex. Various scientific views have been expressed on its form in the 5th c. BC, when Ancient Drama reached its peak; simpler, possibly to a large extent wooden and not semi-circular, it used to occupy only part of the site where it stands today.

After the mid-4th c. BC, the auditorium acquired its huge extension with its massive stone construction, based on circular design. This ambitious project is attributed to the rhetor and politician Lykourgos, who managed public finances in Athens approximately between 338 and 324 BC.

The overall shape of the auditorium is slightly irregular; to the east it is defined by the Odeon of Perikles, which pre-existed from the 5th c. BC, to the south by the retaining walls of the parodoi, to the west and parlly to the north by the western retaining walls and to the north by the Katatomi - the curvilinear vertical cut of the rock of the Acropolis, where siands prominently the choregic monument of Thrasyllos. The Peripatos, the public walkway that encircled the Acropolis, divided the auditorium in a lower and an upper part (ima cavea and summa cavea), serving at the same time as an internal horizontal passageway in the theatre (diazoma).

Fourteen stairways in a radial disposition divide the auditorium in thirteen wedge-shaped sections (cunei). The theatre's tiers of bench-like seats are formed of large well-carved limestone blocks from the quarries at the coastline of Piraeus. The thrones of the first row (proedria), made of Pentelic marble, are not just luxurious seats, but also splendid works of marble sculpture per se. In the middle of this first row stands prominently the marble throne for the priest of Dionysos.

Some interventions during the Roman times are visible in the lower parts of the central sections (cunei). They include the placement of marble thrones, either new or coming from the pre-existing proedria, inscribed pedestals, as well as a staircase that probably used to lead to a loge. These constructions were installed either by means of partial destruction of the seats or with new stone blocks carved appropriately to adapt to the existing seats.

The Theatre of Dionysos was abandoned after the end of Antiquity and during the Middle-Ages the traces of its auditorium gradually disappeared beneath an accumulation of fill. The area occupied by the auditorium was left outside the late Roman fortification wall of Athens, then it was included within the land defined by the wall built in the 13th c. around the Acropolis (Rizokastro) and, in the late Ottoman period, within the limits of the city which was surrounded by a new wall, erected in 1778 by the then city governor (voevod) Hacı Ali (Haseki), It was revealed after successive excavation campaigns undertaken between 1862 and 1895.

A restoration project that started in 2005 concerns the upper parts of the preserved seating area and aims at the passive protection of the monument and a better display of its original form. The "lacunae" between seats are filled in with reintegrated scattered ancient seats as well as newly carved blocks that exactly follow the ancient form. Works in every section of the auditorium are limited to the point that is deemed necessary in order to support the uppermost preserved ancient stone seat.

Another sign here provides some general information about the theatre:

THE THEATRE OF DIONYSOS ELEUTHEREUS

It is in this place that the ancient theatre was born and developed, both as an artistic and as an architectural concept. It originated from the ancient temple of Dionysos and the higher plateau (called the orchestra) to the north of the god's sanctuary, the final destination of the festive procession in the Great Dionysia and the venue for the circular Dionysian dances performed by worshipers wearing animal and satyr masks, singing the Dithyramb in the god's honour to the sound of the aulos. Thespis is recorded as the founder of the earliest documented tragic play, during the Dionysia of 534 BC, at which he also took first prize. Comedy and satyr plays were only added to the theatrical competition later.

The first theatre (theatron), the place where the spectators sat, extended over the southern slope of the Athenian Acropolis. The ancient sources refer to the ikria, a wooden framework of huge wooden posts supporting the seats, and that the first theatre was indeed constructed out of wood has been confirmed by recent archaeological evidence. The wooden infrastructure of the theatre was renovated and extended with the addition of a stage building after the mid-5th c. BC as part of the Periclean building program which envisaged religious and cultural venues - the monumental Odeon of Pericles, for instance, which was built to the east of the theatron - on the southern slope of the Acropolis. Work on Athens' first monumental stone theatre was interrupted by the devastating Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), but would ultimately after the mid-4th c. BC, largely due to the skillful fiscal policies of Eubulus and Lycurgus. The architectural design of the new Athenian theatre revolved around the circular orchestra and serves as the theatrical archetype to this day. Its capacity is estimated to have been between 17.000 and 19,000.

In the years that follow, theatre types evolved in parallel with broader sociopolitical changes, which triggered extensive alterations to the stage building. The I-shaped facade flanked by projective wings (paraskenia) at both ends was remodelled and monumentalized during the Roman period with the addition of a second storey (scaenae frons). During the reign of the philhellene emperor Hadrian (AD 117-138). in particular, the theatre, now an impressive structure, assumed a new role, hosting celebrations of the emperor as a New Dionysos. The stage was adomed with monumental statues personifying the three genres of Dramatic Poetry (Tragedy, Comedy and Satyr Play), while thirteen bases for statues of the emperor were installed among the seats, with honorary thrones higher up and a tall podium for the throne of the emperor himself.

In 267 AD the theatre suffered extensive damage during the Herulian raids, but regained some of its lost glory when the stage front (the so called Phaedrus Bema after a dedicatory inscription of the 4th c. AD) was repaired and embellished with reliefs, carved on stones which originally formed part of the sanctuary's now-destroyed Hadrianic altar, depicting scenes from the life of the god. The edict banning pagan religion, coupled with the construction of the early Christian Basilica in the 6th c. AD at the eastern entrance,

mark the termination of the theatrical function of a structure linked to numerous highlights in the history of human culture.

Again, looking at more columns and stone pieces on the south side of the path.

We walked a few steps more to reach the eastern parados of the theatre.

A sign describes the sculptures that were here:

HONORARY MONUMENTS OF DRAMATIC POETS AT THE EASTERN PARODOS

The eastern parodos was the main entrance into the theatre, through which priests and officials arrived for the theatrical performances during the Dionysian festival of the city. The northern side of this entrance was chosen as the site for the erection of statues honoring the most important dramatic poets, who symbolized the perennial values of classical education and functioned as examples for participants in the theatrical contests.

The programme for the building and completion of the new stone theatre during the Lycurgan era (336-324 B.C.), as the ancient sources inform us, also included the erection of the posthumous honorary monument to the three Tragedians (Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides) in the main entrance, in around 330 B.C. Their bronze statues, which are preserved in Roman copies, were mounted as a sculptural group on a long base with three steps in front of the parodos' retaining wall. The stones of this base were dismantled during the 19th century and have not yet identified. The statues represent the three Tragedians, who served the glory of classical Athens, in typical poses and in the clothes of distinguished Athenian citizens.

East of this monument the honorary base and statue of the most important representative of the New Comedy, Menander, was erected in 291/0 BC. He wrote over 100 plays, but won the contest only few times. His innovative work focused on ordinary people and he is considered the father of psychological drama. At the age of only 51, he drowned while swimming off Piraeus. The monument in his honour was erected immediately after his death while Athens was under the rule of the Macedonian King, Demetrios Poliorketes. The poet is represented seated on an honorary throne, his beardless face mirroring the new fashion introduced by Alexander the Great.

The ancient base of his statue, which was revealed in 1862, is inscribed with the name of the poet, as well as the signatures of the sculptors, sons of the famous sculptor Praxiteles. The inscription

reads: 'Kefisodotos and Timarchos made it'. The original statue was copied many times during the Roman era, because of the Romans' particular admiration for the plays of Menander. The identification of the position and form of this monument permitted its restoration, with the reconstruction of the two lost steps of the bathron, the repositioning of the ancient base, and the didactic use of a cast replica in place of the lost bronze original.

Of the six bases which once stood at this entrance, one other, the base of the statue of an unknown poet, most likely from the 2nd century BC, could be restored at the western part of the parodos. Its lost steps during the 19th century were constructed with new stone, and the two newly identified ancient stones from the base have been returned to their initial position again.

The restoration programme was completed in 2012 by the Scientific Committee responsible for the monuments on the Acropolis South Slope.

Another nearby sign describes the retaining wall of the eastern parados:

THE THEATRE OF DIONYSOS

The retaining wall of the Eastern Parodos

The retaining walls of the parodoi (passages) of the Theatre of Dionysos are one of the characteristic elements of the stone construction of the theatre, which was built, fully in stone, during the archonship of Lycurgos (336-324 BC). The retaining wall of the Eastern Parodos marks the area of the main eastern entrance to the theater and at the same time supports the made-up earth laid on which the rows of stone seats of the auditorium were embedded. This entrance connects the theatre with one of the main roads of the city, the famous Street of the Tripods, was marked at first by a wooden Doric gate, that was replaced by a new monumental marble Propylon, constructed in lonic order, in the period of the Roman emperor Augustus (27 BC-14 AD). A twin propylon was also constructed in the western parodos. At the sides of the east entrance and mainly in front of the retaining wall bases with honorary statues of the most famous poets of Greek Drama were erected. Some new monuments were added in the Hellenistic and Roman time. The major destruction of the Theatre was caused by the raiding groups of Heruli, in 267 AD. In the 6th century AD with the establishment of Christianity a one aisled basilica was constructed in the main entrance, while the orchestra was transformed into the courtyard of the church.

In Late Antiquity, the stones of the retaining wall were removed. This was the main reason for the destruction of this section of the theatre. After the excavations in the theatre at the middle of the 19th century and the progressive damage to the remains of the wall, many static problems have arisen during the last decades. It became necessary to support and partially reconstruct this wall. The restoration project was a priority of the programs of the Monuments Committee. Work began in 1996 and was completed at the end of 2003. The limestone was quamied from the area which belongs to the Chatzikyriakos-Foundation in Peiraius, as in ancient times. This material was used for the partial reconstruction of the retaining wall. The inner supporting walls which had been built of conglomerate stones were replaced with artificial stones. These conglomerate constructions were revealed as result of this research project. For the partial reconstruction of the retaining wall 174 new limestone blocks from Peiraius were put in place and 11 repairs were made for missing parts of the ancient stones. 103 artificial conglomerate stones were also moulded.

This was the view looking to the southwest from the path. This was about as far east as we could go. We could either turn right and go south, which would lead back to the entrance, or backtrack to the west.

We returned to the west.

This was the Choregic Monument of Nikias. It is described as something like a small temple.

A sign provides some more detail:

THE CHOREGIC MONUMENT OF NIKIAS

West of the road leading from the Sanctuary of Dionysos to the Acropolis there is a magnificent choregic monument. The institution of the Choregy, in operation from the late 6th century B.C., involved wealthy Athenians who bore the expense for the preparation of performances in dithyrambic or dramatic contests. The events took place in the theatre during the festival of Dionysos, called the Great or ("en Astei", in the city) Dionysia in the month Elaphebolion (late March-early April). The prize for the winner in dithyrambic contests of boys or men was a bronze tripod, dedicated by the patron (Choregos) to the god Dionysos, preferably in a conspicuous place near the sanctuary and the theatre of Dionysos.

The monument of Nikias was a small temple-like, with six Doric columns in front and pediments on both its narrow sides. At the end of the antiquity (3rd cent. A.D.) the monument was dismantled and a large number of its architectural members were transferred and used to construct the Beulé gate of the Acropolis, named after its excavator. Visitors can still find there the choregic inscription, engraved on the three central sections of the architrave of the façade, referred to Nikias, son of Nikodemos, who won teaching the chorus of the boys in the archonship of Neaichmos (320/319 B.C.).

The Stoa of Eumenes, built 160 years later, fully respects the position of the choregic monument of Nikias. Scattered architectural members, which belong to it, have been gathered and placed at the positions corresponding to those they once occupied in the structure of the building.

There isn’t really anything to the west here other than a jumble of stone building pieces. A bit reminiscent of Rome here!

The Stoa of Eumenes, which was briefly mentioned on the previous sign, is here. Although, it seems that the structure that we see here when looking to the northwest is actually the retaining wall that is to the north of the stoa.

A sign here describes this stoa:

STOA OF EUMENES II

The Stoa of Eumenes is placed between the Theatre of Dionysos and the Odeion of Herodes Atticus, along the Peripatos (the ancient road around the Acropolis). The king of Pergamon, Eumenes II, donated this Stoa to the Athenian city, during his sovereignty, which endured from 197 B.C. to 159 B.C. This elongated building, 163.00 m. long and 17.65 m. wide, had two storeys. The ground floor façade was formed from a colonnade of 64 doric columns, while the interior colonnade consisted of 32 columns of lonic order. On the upper storey, the exterior colonnade had the equivalent number of double-semicolumns of Ionic order and the interior columns had the rather rare type of capitals, the Pergamene ones. Nowadays, a visible part of the monument is the north retaining wall, reinforced with buttresses connected by semicircular arches. This wall was constructed in order to hold the north earth embankment in place and to support the Peripatos. Today are also visible: the Krene (spring) included in the north wall, the stylobates of the inner colonnade on the ground floor and the foundation of the exterior colonnade. Besides, a part of the substructure of the east wall of the stoa has also survived, in addition to the west wall, who suffered some changes during the Roman period, when the Odeion of Herodes Atticus was erected.

We continued by walking to the north. The path spits in two up ahead with options to go east or west.

We were hoping to go east as we planned on walking counter-clockwise around the Acropolis. However, the path was blocked ahead.

So, no east! Only west up this ramp.

The next structure that we encountered was the Sanctuary of Asklepios. The three columns in the background are part of the Doric stoa which was behind this sanctuary.

A sign here describes this structure:

THE SANCTUARY OF ASKLEPIOS

The Asclepieion, the sanctuary of the god Asclepios and his daughter Hygieia, the personification of "Health", is located to the west of the Theatre of Dionysos, between the Acropolis and the Peripatos, i.e. the road which used to surround it. The Sanctuary was founded in the year 420/19 B.C. by an Athenian citizen from the deme of Acharnai, named Telemachos. The founding of the Asclepieion is recorded in the Telemachos Monument, a votive stele consisting of a narrow shaft, crowned by two slabs with relief panels, which commemorate the arrival of the god in Athens from the Sanctuary of Epidaurus and present him in his new residence at the sanctuary on the South Slope of the Acropolis. A copy of the Monument of Telemachos is exhibited today in the Doric stoa of the sanctuary.

Entrance from the Peripatos to the two courts of the sanctuary was made through a monumental entrance (propylon), which, according to epigraphic sources, was renovated in Roman times. The eastem court, which was entered through a porch at the westem side, included the temple and altar of the god as well as two stoas, the so-called Doric Stoa at the north side and the so-called Roman Stoa at the south side, which was added in the roman period, to accomodate the ever increasing pilgrims to the sanctuary. The Doric Stoa served as an incubation hall for the visitors to the Asclepieion, who stayed there ovemnight and were miraculously cured by the god, who appeared in their dreams. The lonic stoa (Katagogion), which was the most important building of the wester court, served as a guest-house and refectory for the priests and the visitors to the shrine.

The Temple of Asclepios is a building of the Ist century B.C., with a two-column in antis façade and a small cella, which, according to Pausanias, who visited Athens in the 2nd century A.D., housed the statues of Asklepios and his children. In the 3rd century A.D. it was expanded eastwards, in order to create a four-column façade, with a wider pronaos.

The Doric Stoa, a two-storey building with a façade of 17 Doric columns, was built in 300/299 B.C., as epigraphical testimonies attest. The stoa integrated into its easter part the Sacred Spring, i.e. a small cave with a spring in the Acropolis rock, since water has always been a significant element in the cult of Asclepios, and into its wester part the Sacred Bothros, which functioned as a sacrificial pit. The Sacred Bothros, was a well built with polygonal masonry, in the mezzanine floor of the stoa. It is dated earlier than the stoa itself, to the last quarter of the 5th century B.C. In this part of the sanctuary took place the Heroa, i.e. the sacrifices to the chthonian deities and the Heroes.

The lonic Stoa, is also dated to the last quarter of the 5th century B.C. It was a one-storey building with four rooms and a colonnade with ten ionic columns of excellent quality.

In the 6th century A.D., when Christianity replaced paganism, all the buildings in the Asklepieion were integrated into the complex of a large three-aisled Early Christian basilica. In the Byzantine period (I Ith and 13th century) two smaller, single-aisle churches were erected on the site of the basilica. The last one probably functioned as the katholikon of a small monastery.

After 2002, the west part of the Doric Stoa's ground floor, the Sacred Bothros and the temple of Asklepios were partly restored.

We continued walking along the path to the west.

The path turns here at the Byzantine Cistern.

The path briefly goes north, presumably just to go around the Byzantine Cistern. From here, just to the north a bit of where the path was and looking to the east, we can see the columns of the Doric stoa that we just saw.

This path that we are would have been behind the Stoa of Eumenes. Looking to the southwest, we can see the Philopappos Monument atop the Philopappou Hill. We plan on visiting, though likely not today.

Looking to the southeast, the only thing that is easily identifiable is the Acropolis Museum, the glass sided building left of center. Another place that we plan on visiting, just not today.

There were marble steles under a protective canopy on the north side of the path. To the north, the hill transitions to something more like a cliff.

We also saw some stone building pieces placed on the ground in a relatively neat fashion.

There were some bronze foundries here, one of which was within this low modern stone wall. There isn’t really anything to see though as the excavation site has been covered with dirt.

A sign describes these foundries:

BRONZE FOUNDRIES

The area west of the Sanctuary of Asklepios was a site of manufacture in antiquity (5th-4th cent. B.C.). Excavations from 1877 to 2006 have revealed a total of four pits cut into the soft rock (kimelia) of the Acropolis that are connected with the process of casting bronze statues. The two largest pits (A and B), depth of 2.80 m, are accessed by stairways and have facilities in their interior.

Foundry A to the west, excavated in 1877 and 1963, is defined by the modern wall and has now covered over with earth. Its lower level consists of two facilities. The better-preserved installation, on the southwest side is enclosed by a brick wall and includes a rectangular

base of porous stone with rounded corners, plastered over with clay. A clay channel runs around this structure, ending at each of the four corners to spouts for the disposal of the metal waste and the melted wax used in casting. The second facility, on the northeast side, is preserved in stretches. It retains a part of an oval base, a clay channel, and is enclosed by a brick wall. At the west there is an ancillary chamber with a small pit and a clay channel. At a higher level the remains of a subsequent installation with clay-covered trough, have been revealed.

Foundry D to the east, protected under the shed, was excavated in 2006 and has a square base of clay-plastered porous plinths at its center. Its southern section preserves the trace of a mould of a statue, depicting the termination of long garment folds. A brick wall, height of 1.30 m, is preserved on both the southern and the eastern sides. On the floor, two clay-covered basins were carved for ancillary purposes. After the casting process was completed, the pits were covered over with earth and the wall that rests on the western part of the Foundry D was built. During the excavation of the pit, thou- sands of mould fragments were collected.

The extensive manufacturing activity in the area is connected either with the monuments of the Asklepieion or with those on thie <illegible> Acropolis; according to one view, here was the <illegible> statue of Athena Promachos, Pheidias' work <illegible> Acropolis, was cast.

This is the Foundry D that was described on the previous sign. Unfortunately, the transparent protective covering was completely caked over with sand and dust.

By now, we were nearing the western end of the Acropolis. Looking up, we could see the top of the west side of the Parthenon.

Continuing along the path to the west, we could see a tall structure ahead.

We have reached the Odeon of Herodes Atticus. The tall structure that we saw, which is now at the left edge of the frame, seems to be what was described as the stage building.

There are two ways to proceed here. One is via a narrow path right above the theatre’s seating. The other goes up above. We decided to take the narrow path. There were actually some stairs as well which we walked on to reach this point here.

There are some ugly modern steel structures here as this theatre is still in use today!

The path around the top of this theatre was pretty crowded, though that was only because it was so narrow. So far, other than when there were tour groups moving through, it wasn’t too busy.

The view looking uphill. It does look a bit busy up there.

We continued on until we reached the end of the path on the west side of the theatre. Presumably, there was a sign somewhere describing this theatre. We seem to have missed it.

From here, it was time to head up and actually ascend to the top of the Acropolis.

The main entrance to the Acropolis is actually just to the west of here at the bottom of a gentle slope.

We followed the path in the opposite direction to go up.

As we ascended, we looked down to see the stage building of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus below us.

We reached the area we saw before where there were many people looking down. We, of course, looked down as well to see the theatre below.

This path, to the east, is the one we did not take earlier when we arrived at the Odeon of Herodes Atticus.

There isn’t really anything here. Just some trees and stone building pieces. So, we continued on.

Just to the north was the Propylaea, the entrance to the Acropolis. This area was extremely busy!

The view looking down from part of the way up.

The final modern stairs leading up to the Acropolis.

Again, the view looking back after ascending a bit more.

The Propylaea, as viewed from the east side. There was also a shrine, the Shrine of Athena Hygieia and Hygieia. The Wikipedia article on Athena describes this confusing Athena Hygieia nomencalture:

The Greek biographer Plutarch describes Pericles's dedication of a statue to her as Athena Hygieia (Ὑγίεια, "Health") after she inspired, in a dream, his successful treatment of a man injured during the construction of the gateway to the Acropolis.

The Propylaea was damaged while the Ottoman Empire ruled Athens. It was used to store gunpowder and exploded in 1640!

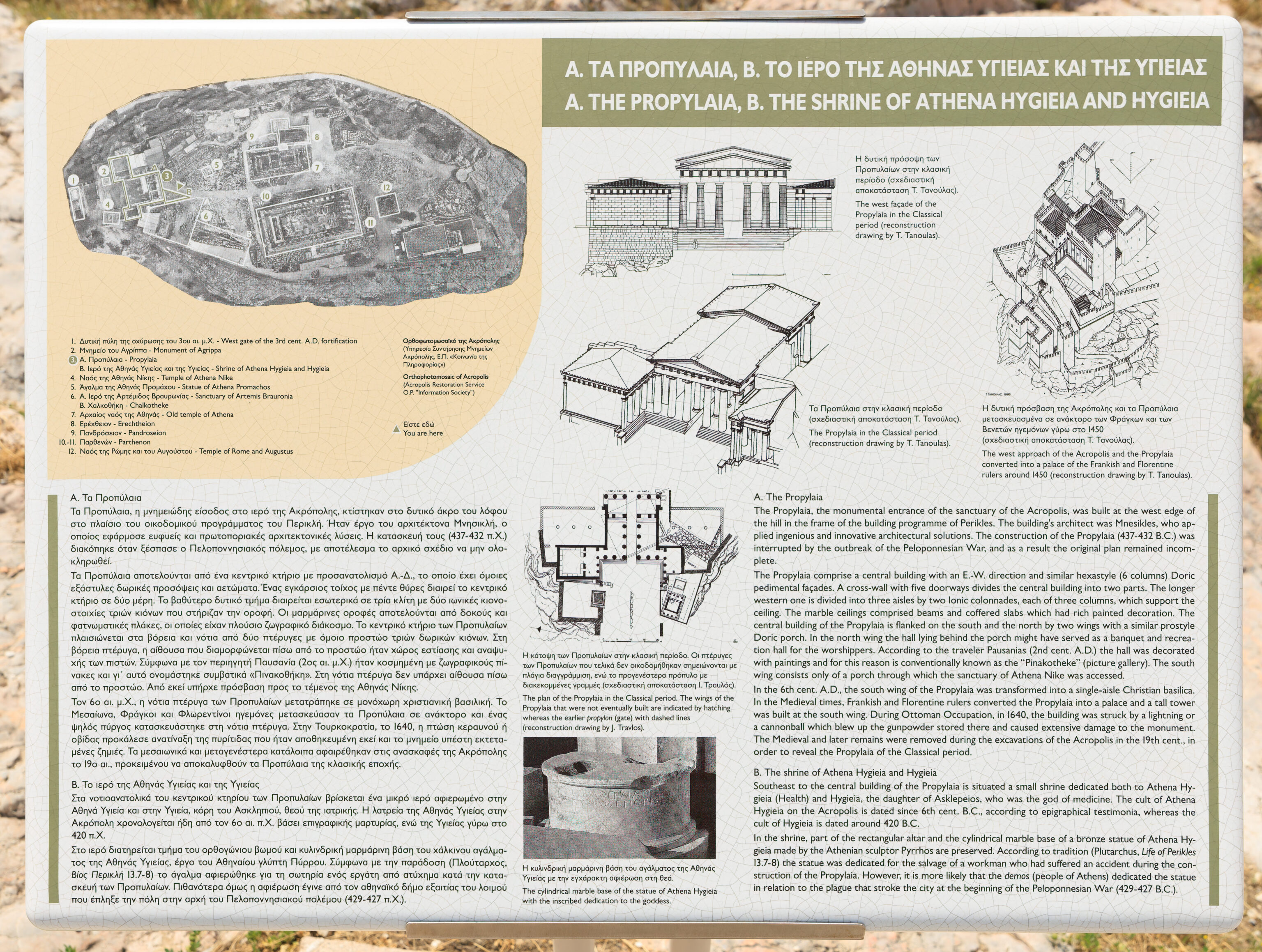

This sign describes the Propylaea and the shrine. It also has drawings of how the Propylaea appeared in the past as well as a useful map of the top of the Acropolis.

The English text on the sign reads:

A. THE PROPYLAIA, B. THE SHRINE OF ATHENA HYGIEIA AND HYGIEIA

A. The Propylaia

The Propylaia, the monumental entrance of the sanctuary of the Acropolis, was built at the west edge of the hill in the frame of the building programme of Perikles. The building's architect was Mnesikles, who applied ingenious and innovative architectural solutions. The construction of the Propylaia (437-432 B.C.) was interrupted by the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, and as a result the original plan remained incomplete.

The Propylaia comprise a central building with an E.-W. direction and similar hexastyle (6 columns) Doric pedimental façades. A cross-wall with five doorways divides the central building into two parts. The longer western one is divided into three aisles by two lonic colonnades, each of three columns, which support the ceiling. The marble ceilings comprised beams and coffered slabs which had rich painted decoration. The central building of the Propylaia is flanked on the south and the north by two wings with a similar prostyle Doric porch. In the north wing the hall lying behind the porch might have served as a banquet and recreation hall for the worshippers. According to the traveler Pausanias (2nd cent. A.D.) the hall was decorated with paintings and for this reason is conventionally known as the "Pinakotheke" (picture gallery). The south wing consists only of a porch through which the sanctuary of Athena Nike was accessed.

In the 6th cent. A.D., the south wing of the Propylaia was transformed into a single-aisle Christian basilica. In the Medieval times, Frankish and Florentine rulers converted the Propylaia into a palace and a tall tower was built at the south wing. During Ottoman Occupation, in 1640, the building was struck by a lightning or a cannonball which blew up the gunpowder stored there and caused extensive damage to the monument. The Medieval and later remains were removed during the excavations of the Acropolis in the 19th cent., in order to reveal the Propylaia of the Classical period.

B. The shrine of Athena Hygieia and Hygieia

Southeast to the central building of the Propylaia is situated a small shrine dedicated both to Athena Hygieia (Health) and Hygieia, the daughter of Asklepeios, who was the god of medicine. The cult of Athena Hygieia on the Acropolis is dated since 6th cent. B.C., according to epigraphical testimonia, whereas the cult of Hygieia is dated around 420 B.C.

In the shrine, part of the rectangular altar and the cylindrical marble base of a bronze statue of Athena Hygieia made by the Athenian sculptor Pyrrhos are preserved. According to tradition (Plutarchus, Life of Perikles 13.7-8) the statue was dedicated for the salvage of a workman who had suffered an accident during the construction of the Propylaia. However, it is more likely that the demos (people of Athens) dedicated the statue in relation to the plague that stroke the city at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War (429-427 B.C.).

The area around the Propylaia was also home to the Temple of Athena Nike. This seems to have been a structure on the west side of the Propylaia. It might be the columned building seen here behind the left side of the Propylaia.

A sign describes this small temple:

THE TEMPLE OF ATHENA NIKE

The small temple on top of the bastion which since the Mycenaean period (late 13th cent. B.C.) guarded the southwest end of the hill of the Acropolis, was dedicated to the goddess Athena Nike, protector of the city who offered the Athenians victory in their battles. It is dated to the Classical period (427 424 B.C.) and belongs to the building programme of Perikles. A marble balustrade, which was decorated with representations in relief of winged Nikai (Victories) and figures of seated Athena, was constructed later (415-405 B.C.), in order to protect the three sides at the top of the bastion and to define the sanctuary of the goddess. The Classical temple was built at the site of an earlier small temple made by poros stone, dated after 468 B.C., which housed the xoanon, the wooden cult statue of the goddess. A considerable part of this temple and remains of the early shrine (Ist half of the 6th cent. B.C.) are preserved in a specially arranged basement space in the Classical bastion.

The Classical temple, made of Pentelic marble, was built in the lonic order with four columns at the front and rear end, and measured 3.12 X 2.46 meters. It is attributed to the architect Kallikrates. The temple's rich sculptural decoration praises the victorious battles of the Athenians. From the preserved architectural sculptures it is assumed that the Gigantomachy - battle between gods and giants - was presented on the east pediment, and the Amazonomachy - battle between Athenians and Amazons - on the west. The lonic frieze, which runs along the upper part of the temple depicts battles between Greeks and Persians (south side), battle of Greek warriors (hoplites) against other warriors (north and west side), while on the east side the assembly (agora) of the Olympian gods. The corners of the pediments were decorated with gold-plated bronze Nikai (acroteria).

The monument was torn down during the Ottoman occupation in 1686, on the eve of the incursion into Attica of the Venetian troops under the command of general Francesco Morosini, and its architectural members were incorporated in the bastion constructed in front of the Propylaia. After the demolition of the bastion in 1835, the architectural members of the temple were recovered.

And, to the east, we have the Parthenon! There was scaffolding around some of the structure for restoration activities. As a result, we weren’t able to get any closer from the south side.

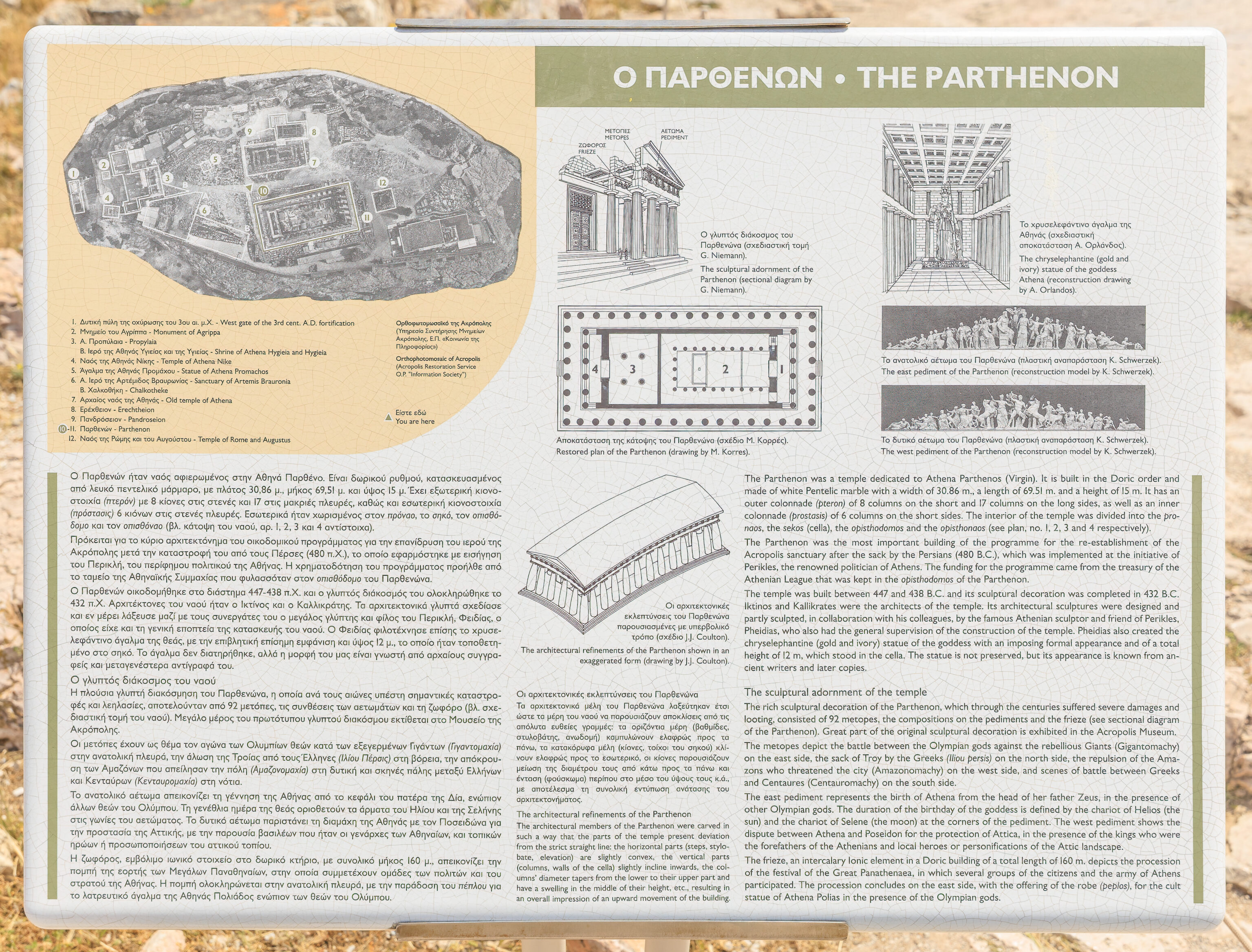

We actually saw this sign later on the north side of the Parthenon. However, it provides an overview of this temple, dedicated to Athena, so it makes more sense to include it here.

The English text on the sign reads:

THE PARTHENON

The Parthenon was a temple dedicated to Athena Parthenos (Virgin). It is built in the Doric order and made of white Pentelic marble with a width of 30.86 m., a length of 69.51 m. and a height of 15 m. It has an outer colonnade (pteron) of 8 columns on the short and 17 columns on the long sides, as well as an inner colonnade (prostasis) of 6 columns on the short sides. The interior of the temple was divided into the pronaos, the sekos (cella), the opisthodomos and the opisthonaos (see plan, no. I, 2, 3 and 4 respectively).

The Parthenon was the most important building of the programme for the re-establishment of the Acropolis sanctuary after the sack by the Persians (480 B.C.), which was implemented at the initiative of Perikles, the renowned politician of Athens. The funding for the programme came from the treasury of the Athenian League that was kept in the opisthodomos of the Parthenon.

The temple was built between 447 and 438 B.C. and its sculptural decoration was completed in 432 B.C. Iktinos and Kallikrates were the architects of the temple. Its architectural sculptures were designed and partly sculpted, in collaboration with his colleagues, by the famous Athenian sculptor and friend of Perikles, Pheidias, who also had the general supervision of the construction of the temple. Pheidias also created the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of the goddess with an imposing formal appearance and of a total height of 12 m, which stood in the cella. The statue is not preserved, but its appearance is known from ancient writers and later copies.

The sculptural adornment of the temple

The rich sculptural decoration of the Parthenon, which through the centuries suffered severe damages and looting, consisted of 92 metopes, the compositions on the pediments and the frieze (see sectional diagram of the Parthenon). Great part of the original sculptural decoration is exhibited in the Acropolis Museum.

The metopes depict the battle between the Olympian gods against the rebellious Giants (Gigantomachy) on the east side, the sack of Troy by the Greeks (Iliou persis) on the north side, the repulsion of the Amazons who threatened the city (Amazonomachy) on the west side, and scenes of battle between Greeks and Centaures (Centauromachy) on the south side.

The east pediment represents the birth of Athena from the head of her father Zeus, in the presence of other Olympian gods. The duration of the birthday of the goddess is defined by the chariot of Helios (the sun) and the chariot of Selene (the moon) at the corners of the pediment. The west pediment shows the dispute between Athena and Poseidon for the protection of Attica, in the presence of the kings who were the forefathers of the Athenians and local heroes or personifications of the Attic landscape.

The frieze, an intercalary Ionic element in a Doric building of a total length of 160 m. depicts the procession of the festival of the Great Panathenaea, in which several groups of the citizens and the army of Athens participated. The procession concludes on the east side, with the offering of the robe (peplos), for the cult statue of Athena Polias in the presence of the Olympian gods.

From the southern edge of the Acropolis, we could see the Odeon of Herodes Atticus below and the Philopappos Monument further away. We could also see the Mediterranean, just a few miles away.

Looking to the southeast, we could see the Theatre of Dionysos below and the Acropolis Museum beyond it Further away, we could see the Temple of Olympian Zeus, which we visited yesterday, as well as the Panathenaic Stadium, which we also visited yesterday.

We could not walk all the way to the east along the southern edge of the Acropolis due to the restoration activities taking place.

It was pretty hot out in the sun. This cat had the right idea!

There were many stone building pieces on the ground here. There was even a broken cannon and some cannonballs!

As we could not walk any further east, we turned to the north to arrive at the east end of the Parthenon.

A sign here describes the Parthenon:

THE PARTHENON

The Parthenon, a temple of the Doric order, was dedicated to Athena Parthenos (Virgin). It was the most important building of the programme of Perikles for the re-establishment of the Acropolis sanctuary after the sack by the Persians in 480 B.C. The architects of the temple were Iktinos and Kallikrates. The renowned sculptor Pheidias collaborated with other sculptors to design and execute the abundant sculptural decoration of the temple, created the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Athena which stood in the cella, and had the general supervision of the construction of the temple. The Parthenon was built in 447-438 B.C. and its sculptural compositions were completed in 432 B.C.

In the following centuries, several votive offerings were added to the Parthenon, among which most characteristic were the bronze shields which Alexander the Great dedicated from the spoils of his victory at the Granikos river (334 B.C.). The shields hung along the east architrave, as indicated by the large rectangular holes. The bronze letters of a decree by the Athenians in honour of the Roman emperor Nero (61 A.D.) were fastened in the smaller closely grouped holes on the east architrave.

In the late 3rd or late 4th cent. A.D., the interior of the temple was destroyed by fire either by the Germanic tribe of the Heruli (267 A.D.) or by Alaric's Visigoths (396 A.D.). During the early Christian period (6th cent. A.D.), the Parthenon was converted into a church dedicated to the "Holy Wisdom" and in the Ilth cent. A.D. to Panagia Athiniotissa (Virgin Mary). During the construction of the Christian apse at the east porch (pronaos), the central scene of the east pediment with the birth of Athena was lost. In 1204, the Frankish crusaders, the dukes De la Roche, besieged Athens and converted the monument into a Catholic church of Notre Dame. When Athens was surrendered to the Ottoman Turks in 1458, the temple became a mosque with a minaret.

In 1687, during the siege of the Acropolis by the troops of Venetian general Francesco Morosini, a cannonball made a direct hit in the interior of the temple, which the Turks used as a powder magazine. The terrible explosion blew up the roof and destroyed the long sides of the temple as well as parts of its sculptures.

The most severe damage to the monument was caused in 1801-1802, when the Scotch ambassador of England to Constantinople Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, removed the greatest part of the sculptures that also comprised structural members of the temple. By bribing the Turkish garrison of the Acropolis and employing teams of the Italian artist G.B. Lusieri, Elgin removed and transported to England 19 pedimental sculptures, 15 metopes and the reliefs of 56 sawn blocks of the frieze, today exhibited in the British Museum in London.

This small clump of columns and stone building parts, just to the east of the Parthenon, was the Temple of Rome and Augustus. It is the only Roman temple here on the Acropolis and is believed to have been dedicated to Roma, the personification of Rome, and the emperor Octavian, the first Roman emperor.

A sign provides some details about this temple:

THE TEMPLE OF ROME AND AUGUSTUS

East of the Parthenon lay the foundations of a small building attributed by the first excavators of the Acropolis to the Temple of Rome and the Roman Emperor Octavian Augustus. The association of the foundations with the temple stems from the discovery in the area of many marble architectural members, as well as of the architrave bearing the incised dedicatory inscription.

The architectural members indicate that the Temple of Rome and Augustus was of the Ionic order, circular and monopteral - namely that it featured a single circular colonnade made of nine columns (pteron), without a walled room inside (cella). Its diameter measured ca. 8.60 m. and its height reached 7.30 m. up to the conical roof. The construction of the temple is associated with the architect who repaired the Erechtheion in the Roman Period, because the architectural details of its members replicate those of the Erechtheion. It is possible that the temple interior housed statues of Rome and Augustus, although no fragments of sculptures have been identified to date.

The temple of Rome and Augustus is the sole Roman temple on the Acropolis and the only Athenian temple dedicated to the cult of the Emperor. The Athenian deme (people) constructed it in order to propitiate Octavian August and reverse the negative climate that characterized the relations of the two parties, as, during the Roman civil wars, the city of Athens had supported his opponent, Marcus Antonius.

The temple is securely dated after 27 B.C., when Octavian was proclaimed Augustus - most probably between 19 and 17 B.C.

This wide stone architrave from the temple contains inscribed text. The sign for this temple has some text about this inscription in Greek and English:

Ο δήμος (αφιέρωσε) στη θεά Ρώμη και στον Σεβαστό Καίσαρα (Αύγουστο)

όταν στρατηγός των οπλιτών ήταν ο Παμμένης, γιος του Ζήνωνος από τον

Μαραθώνα, ο ιερεύς της Θεάς Ρώμης και του Σεβαστού Σωτήρος στην

Ακρόπολη, όταν ιέρεια της Αθηνάς Πολιάδος ήταν η Μεγίστη, κόρη του

Ασκληπίδη από το δήμο των Αλών. Όταν άρχοντας ήταν ο Άρηος, γιος του

Δωρίωνος από την Παιανία.

The deme (dedicated) to the goddess Rome and Sebastos Caesar (Augustus), when general of the hoplites was Pammenes, son of Zenon from Marathon, the priest of the goddess Rome and Sebastos Soter on the Acropolis; when priestess of Athena Polias was Megiste, daughter of Asclepides from the deme of Halai. When Eponymous Archon was Areos, son of Dorion from Paiania.

This seems like the actual inscribed text rather than a description. Changing the Greek text to all uppercase and removing the words in parenthesis yields:

Ο ΔΉΜΟΣ ΣΤΗ ΘΕΆ ΡΏΜΗ ΚΑΙ ΣΤΟΝ ΣΕΒΑΣΤΌ ΚΑΊΣΑΡΑ ΌΤΑΝ ΣΤΡΑΤΗΓΌΣ ΤΩΝ ΟΠΛΙΤΏΝ ΉΤΑΝ Ο ΠΑΜΜΈΝΗΣ, ΓΙΟΣ ΤΟΥ ΖΉΝΩΝΟΣ ΑΠΌ ΤΟΝ ΜΑΡΑΘΏΝΑ, Ο ΙΕΡΕΎΣ ΤΗΣ ΘΕΆΣ ΡΏΜΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΤΟΥ ΣΕΒΑΣΤΟΎ ΣΩΤΉΡΟΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΑΚΡΌΠΟΛΗ, ΌΤΑΝ ΙΈΡΕΙΑ ΤΗΣ ΑΘΗΝΆΣ ΠΟΛΙΆΔΟΣ ΉΤΑΝ Η ΜΕΓΊΣΤΗ, ΚΌΡΗ ΤΟΥ ΑΣΚΛΗΠΊΔΗ ΑΠΌ ΤΟ ΔΉΜΟ ΤΩΝ ΑΛΏΝ. ΌΤΑΝ ΆΡΧΟΝΤΑΣ ΉΤΑΝ Ο ΆΡΗΟΣ, ΓΙΟΣ ΤΟΥ ΔΩΡΊΩΝΟΣ ΑΠΌ ΤΗΝ ΠΑΙΑΝΊΑ.

There are extra words but it does seem to match the text on the stone.

Further to the east, there is a relatively modern overlook structure at the northeastern corner of the Acropolis. The building on the right, at the southeastern portion of the Acropolis, is the Old Acropolis Museum. It was closed when the current Acropolis Museum opened.

We walked over to the overlook to take a look at the view. Looking to the east, we had a nice view of the Temple of Olympian Zeus and the Panathenaic Stadium.

Looking to northeast, we could see the Lycabettus towering over everything else. Its peak is higher than the Acropolis. The Old Royal Palace is also visible from here. It is the large cream colored building near the right edge of the photograph. The Grande Bretagne is also visible. If you draw an L down from the Lycabettus and to the right to the Old Royal Palace, the hotel is about where the two lines meet.

Looking to the northwest, well, we haven’t been to that part of the city yet! The Ancient Agora is down there all the way on the left. We should have time to visit it. Also visible from here is Hadrian’s Library and the Roman Agora. We’ll visit these minor historical sites if we have time.

After enjoying the view, we started walking to the west back towards the Parthenon.

The overlook and its huge flag, as seen from a short distance away to the west.

We arrived on the south side of the Parthenon. Now, we’re going to walk by its north side.

We passed by a huge field of building part stones! They’re actually pretty well stacked if you take a close look!

We continued walking to the west…

Passing by more stone building parts…

We walked over to the northern edge of the Acropolis to check out the Erechtheion. This temple is named after Erechtheus, the mythological founder of Athens.

A sign provides a description of this temple:

THE ERECHTHEION

This elegant building of the Ionic order is called, according to later literary sources, Erechtheion from the name of Erechtheus, the mythical king of Athens. The construction started before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (431 B.C.) or after the conclusion of the "peace of Nikias" (421 B.C.) and was finished in 406 B.C., after the interruption of the works because of the war.

The peculiar plan of the building is due to the natural irregularity of the ground and the need to house the ancient sacred spots: the salt spring, which appeared when Poseidon struck the rock with his trident during the contest with Athena over the patronage of the city, the trident marks and the tombs of the Athenian kings Kekrops and Erechtheus.

The Erechtheion consists of a rectangular cella divided by an interior wall forming two sections. The eastern section, which was at a level at least 3 m. higher than that of the western, was dedicated to Athena Polias and housed the xoanon, the ancient wooden cult statue of the goddess. The western section was divided into three parts and was dedicated to the cult of Poseidon-Erechtheus, Hephaistus and the hero Boutes.

At the north side of the cella there is a magnificent porch with 6 Ionic columns. The bases and capitals along with the frame of the doorway leading to the interior of the cella, have elaborate relief decoration, while the ceiling coffers were painted. The famous Porch of the Maidens (Korai) or Caryatids dominates the south side of the building: six statues of young women, standing on a podium 1.77 m. high, support the roof of the porch, which was the part of Kekrops' tomb above the ground. At the upper part of the building is a frieze of grey Eleusinian stone to which relief figures of white Parian marble were attached. Today they are exhibited in the Acropolis Museum.

Around the end of the Ist century B.C. the Erechtheion was repaired after a fire. During the Christian period it was transformed into a church, while in the Ottoman period it was used as a house. In the first years of the 19th century Lord Elgin carried off the third Caryatid from the west (Kore C) and the column of the northeast corner of the building. Today they have been replaced by copies, as well as the rest of the Caryatids.

The replica caryatids mentioned on the previous sign are here on the southwestern corner of the Erechtheion. Five of the original caryatids are at the Acropolis Museum while the 6th is on display at the British Museum.

We walked south to get a closer look at the Parthenon.

A sign here described the restoration activities that have taken place in the past as well as some of what is currently being done:

THE RESTORATION OF THE PARTHENON:

WORKS IN PROGRESS AND INTERVENTIONS COMPLETED

The explosion that happened in the bombardment during the 1687 Acropolis siege reduced the Parthenon to ruins. Even though efforts to restore the monument were made during the 1900-1930 period, the use of reinforced concrete and iron joints severely damaged the marble and caused structural problems within the restored sections. Renewed restoration works began on the Parthenon in 1983.

On the temple's east side, works during the period 1984-1991 included restoration of the two corners of the entablature above the columns, as well as replacement of the original metopes with exact replicas (1-2).

The pronaos restoration projects (1995-2004) included partial restoration of the first three northern columns using architectural members whose original positions had been identified, as well as complete restoration of the fourth and fifth columns. The final fluting of the columns' new marble in-fillings drums remains in progress (3-4).

The restoration of the Parthenon's north colonnade, which involved the dismantling, structural restoration, and reassembly of its eight middle columns and overlying entablature, made it possible to correct mistakes from earlier restoration interventions (5).

Works on the long walls of the cella (begun in 2011), according to following the results of new restorational studies, aim to define its boundaries by incorporating all identified members. incorporate all identified members, and so define its bounds. After the completion of the interventions, the two walls will be restored as closely as possible to their post-1687-explosion form (6). While works on the north wall (7) have been on going underway since 2011, restoration of the south wall's orthostates only began recently.

We walked over to the northeast corner of the Parthenon before heading back to the west again.

The space here between the Parthenon and Erechtheion was occupied by the Old Temple of Athena.

A sign describes what was here:

THE "OLD TEMPLE" OF ATHENA

The large Archaic temple to the south of the Erechtheion, which today preserves only its foundations, was called the "Old Temple" according to epigraphic evidence. Dedicated to Athena Polias, the patron deity of the city, it housed the xoanon, the wooden cult statue of the goddess to which the Athenians offered a peplos during the Panathenaic festival. The western section of the temple, consisting of three smaller parts, housed the cults of other divinities, possibly Hephaistus, Poseidon-Erechtheus and the hero Boutes.

Built at the site once occupied by the palace of the Mycenaean ruler of Attica, the temple replaced a smaller Geometric one (8th c. B.C.) also dedicated to Athena Polias. The only remains of this early temple are two stone column bases as well as a bronze disc with an image of Gorgo, which adorned the pediment or the tip of the roof in the 7th c. B.C.

The "Old Temple" of Athena, a Doric peripteral building with 6 columns at the front and rear end and 12 at the sides, measured 43.44 x 21.43 m. It was built of poros, while Parian marble was used for some upper parts, such as the metopes, pedimental sculptures and tiles. One pediment was adorned with a sculpted group illustrating the Gigantomachy (the battle between the Olympian gods and the rebellious Giants), while the other featured a partially preserved group of lions devouring a bull. The altar, which is no longer preserved, was located to the east of the temple, as is indicated by some cuttings on the rock.

The temple was built in 525-500 B.C. and is associated with the sons of the tyrant Peisistratos or the Athenian people at the time of the establishment of Democracy by Kleisthenes. It was destroyed in 480 B.C., during the Persian invasion. Many of its architectural members were later incorporated in the north wall of the Acropolis.

We continued walking west, reaching the western edge of the Parthenon.

We passed by a sign that provides a description of some of the restoration activities that have taken place and are taking place here on the west side of the Parthenon:

THE RESTORATION OF THE PARTHENON:

WORKS IN PROGRESS AND INTERVENTIONS COMPLETED

Works on the Opisthonaos (1992-1993; 2001-2004) included consolidation of the columns with special injected mortars (1997), as well as structural restoration of their capitals and upper drums and of the temple's entablature. The blocks of the west frieze were dismantled and cleaned with laser tools, while replicas in stone were installed in their place (1-2). The works on the west side (2011-2015) involved the removal and structural restoration of architectural members at the two corners of the entablature, including the capitals and the outer parts of the pediment. Newly produced copies were installed in the positions of the seven ancient metopes at the corners that were transferred to the Museum (2, 3, 4).

In June 2017, the conservation and restoration programme of the west pediment began, the primary goal of which was protecting and preserving the monument. It involved the restoration and repositioning of the middle members of the western outer side (tympanum) and inner side (backing wall) of the pediment. During their repositioning, special titanium joints were installed to connect the two sides transversely (5-6). In addition, the full complementation of the tympanum with the use of new marble members has been studied and approved. following the approval of the relevant study being received, the tympanum was augmented with blocks of new marble.

In the upcoming period (2023-2025), restoration works will take place on the roof ceiling of the west wing. These will focus on the restored ancient beams, already restored, the beams produced during the 1950s, and the positioning of all or some of the newer coffered slabs (7).

The Erechtheion, as seen from the southwest corner of the Old Temple of Athena.

We walked to the north by the western edge of the foundation ruins of the Old Temple of Athena. Looking to the west, we could see a steady stream of people arriving and leaving the Acropolis via the Propylaia.

The space here in front of us would have been occupied by a colossal statue of Athena Promachos.

A sign which we saw later when we were to the southwest of here describes this statue:

THE STATUE OF ATHENA PROMACHOS

The colossal bronze statue of Athena, known as Athena Promachos, dominated in the area between the Propylaia and the Erechtheion, to the left of the visitor walking along the processional way of the Acropolis. It was made by the renowned sculotor Pheidias probably at the bronze foundry situated at the southwest siope of the Acropolis. The Athenians dedicated the statue to Athena, co express their graditude for her contribution to the victories in the Persian Wars. Later sources refer that its construction was financed from the Persian spoils. However, according to the inscription with the expense accounts, the construction of the statue is dated to 475-450 B.C.